At the turn of the twentieth century, the Chicago-based architect Dwight Perkins designed a prescient metropolitan plan for the American city that reimagined the polis as a terrain for sociological investigation and political activism. He collaborated with social scientists affiliated with the University of Chicago and with local, grass-roots activists to leverage design as a vehicle for social change. He argued that strategically placed, small-scale interventions would ameliorate the devastating impact that unplanned growth had on the urban poor and that these spaces would advance democratic social ideals in a city highly segregated by race, ethnicity, and wealth.1

Not only was Perkins a pioneer in understanding the city as a heterogeneous collection of cultural groups, he also rethought the manner in which the city was visualized by mediating its architectural representation through the lens of the social sciences. He abandoned illusionistic rendering techniques and illustrated the city as a series of sociological data-maps that combined statistical facts on population density, disease transmission, mortality rates, and criminal activity with geographic projections of Chicago. This new cartographic strategy helped him to identify and create public spaces and social services that benefited underprivileged communities. In doing so, Perkins was one of the first American architects to challenge the socio-economic conditions of the laissez-faire metropolis. Although largely ignored in histories of urban planning and architecture, his nascent social practice contributes to a critical reappraisal of cities that remains relevant today.

The emergence in the 1980s of a neoliberal state predicated on free-market economic policies, deregulation, and excessive privatization of resources has created alarming levels of income inequality, social disparity, and xenophobia that recall the laissez-faire conditions under which Perkins worked at the turn of the twentieth century.2 By mediating the city through sociology, Perkins challenged traditional “bricks and mortar” urbanism that viewed the metropolis primarily as a physical entity. His modest proposals, grass-roots activism, and diagrammatic renderings also challenged utopian visions that advanced provocative yet impractical urban transformations. Refusing to flatten the complexity of modern cities into either empirical facts or fictive ideals, he opened up an actionable middle ground, a “practical utopia” that, in its feasibility, had transformative potential. His example helps us explore questions relevant to contemporary urbanism, such as the efficacy of research-based practices, the ambitions and limitations of community engagement, and the meanings of public space and democracy in cities today.

CARTOGRAPHIC STRATEGIES

Chicago was in a veritable state of emergency when Perkins published his metropolitan plan in 1905. Years of unprecedented and unplanned expansion had produced tremendous growth and profits, but also intractable class conflict, violent labor disputes, unspeakable living conditions, and political corruption. Little more than a frontier outpost in 1840, Chicago ruled an economic empire by 1890 that stretched from the Ohio Valley to the Rocky Mountains, connecting the agricultural and ranching industries of the west with the commercial and manufacturing centers of the east. It dominated the nation’s meat slaughtering and packing industries.3 Remarking on how thoroughly industry had reorganized society, John Dewey, a professor of sociology at the University of Chicago, concluded, “one can hardly believe there has been a revolution in history so rapid, so extensive, so complete.”4 Compounding these challenges was a disproportionately high immigrant population. Foreign-born individuals or children of immigrants made up 77% of Chicago’s population in 1900. Most were uneducated, unskilled laborers who worked primarily in industrial occupations.5 By the turn of the century, Chicago was congested with industrial facilities spewing forth pollution and products alike and manned by an increasingly disgruntled labor force that, together with widespread environmental degradation, threatened democratic self-government in the eyes of many community organizers. Jane Addams, a pioneering social scientist and founder of Hull House settlement, spoke for many when she concluded that “the idea underlying our self-government breaks down” under such circumstances.6

Alarmed by the mounting social and environmental crisis and hoping to galvanize city officials into action, Perkins appropriated statistical analysis techniques pioneered by social scientists at the University of Chicago to create compelling graphics illustrating the socio-urban calamity in his metropolitan plan. Superimposing data on population densities, rates of mortality, infant mortality, diphtheria, typhoid, and crime over Chicago’s street grid, he created five oversized data-maps that served as his principle illustrations (Figure 1).7 Combining such demographic data with geographic projections allowed Perkins to demonstrate that overcrowded, poor communities lacking in mass transportation, quality schools, neighborhood parks, and public spaces were also the most dangerous and unhealthy in the city. These new cartographic strategies are remarkable because they allowed Perkins to map the physical and the intangible city, the built environment and the ephemeral, lived experiences of its inhabitants.

Dwight Perkins, data-map – combines Chicago’s street grid and existing parks with statistics on mortality, infant mortality, diphtheria, typhoid, and juvenile crime.

Two sociologists and political activists, Addams and Charles Zueblin, had experimented with data mapping prior to Perkins, and they strongly informed his methodology and social politics. Perkins worked closely with both reformers through their mutual involvement in Chicago’s settlement movement.8 Social settlements were not charities but privately funded organizations that offered sundry assistance programs to underprivileged people, such as public lectures, continuing education classes, vocational training, legal counsel, childcare, athletic programs, and so on. Through figures like Addams and Zueblin, social settlements evolved in close connection with the new discipline of sociology, then emerging at the University of Chicago. Sociologists considered settlements as a base of operations from which to interact with the urban poor, investigate socio-urban phenomena, collect data, and experiment with solutions to social problems.9 Settlements were, in some ways, sociological laboratories.

Addams collaborated with fellow activist Florence Kelley to spearhead the first sociological investigation of a modern American city, which they published in 1895 as Hull-House Maps and Papers.10 A collection of essays supplemented with factual census schedules and two multicolored maps depicting demographic data on the nineteenth ward in Chicago, the document was a bellwether of the increasing influence that sociology had on urbanism and politics.11 The introduction to Maps and Papers emphasizes the objectivity of the report in which Kelley painstakingly surveyed every house, tenement, and room in the ward and then corroborated the data obtained by cross-referencing responses.12 The authors insisted Maps and Papers simply presented actual conditions versus advancing theories and that, as a result, their method of research was scientific and verifiable.13 Complimenting the quantitative maps were qualitative essays, including one written by Zueblin, examining the cultural conditions of poverty in Chicago, such as sweat labor, slavish factory conditions, government corruption, and ethnic segregation.14 Today it is considered a pioneering sociological tract of environmental determinism.15

Zueblin in particular advocated specific spatial solutions to the social predicaments described in Maps and Papers. Cities, for Zueblin, were preeminently democratic because they were collectives. To this end, he tirelessly lobbied for cities to build squares, parks, schools, and other civic centers – spaces where social democracy could be practiced.16 The public awareness and sense of mutual responsibility that characterized metropolitan life would foster a new civic spirit based on cooperation that, he believed, could ameliorate many of the injustices of the market revolution.17 He advocated for small, neighborhood playgrounds more than any other civic space. In 1898 he published research in the American Journal of Sociology detailing statistics on public park access in Chicago that Perkins later reproduced verbatim in his metropolitan plan. Zueblin’s analysis of population densities and park acreage proved that overcrowded working-class neighborhoods suffered disproportionately from a lack of green space: 4,720 people to each acre of park space compared to 234 people per acre in affluent wards. A map of Chicago combining data on the locations of playgrounds and parks, population density, and railroads proved his point.18

Based on scientifically obtained facts, these emerging cartographic strategies enabled Perkins and his milieu to prove a correlation between the material city and abstract social problems. As a result, he divided the city into four concentric zones and outlined specific architectural interventions for realizing his ambitions.19 He proposed to gradually construct a network of local community centers, such as parks, recreation facilities, public schools, and even a nature preserve – the idea being that together, these spaces would improve public health, educate visitors, and facilitate social exchange, as well as safeguard natural environs as the metropolis expanded.20 These community centers would contain a host of public spaces and services, such as libraries, gymnasiums, showers, meeting rooms, clean-milk dispensing stations, and organized athletics.21 Their convenient neighborhood locations and onsite staff, together with evening and weekend hours made it easy for families, school children, and working adults alike to use the facilities. These centers would join with new and improved public schools to create a geographically widespread network of neighborhood centers capable of advancing social democracy.22

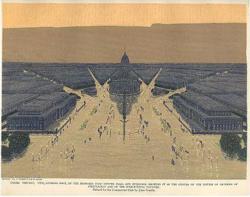

Centered on the seeming banalities of census data, statistical analysis, and quotidian spaces, what was radical about the urbanism advanced by Addams, Zueblin, and Perkins was their willingness to accept the existing conditions of the city and to advocate for local, piecemeal improvements over dramatic and total reorganizations. In this context, a comparison to Chicago’s most celebrated urban renewal scheme, Daniel Burnham’s 1909 Plan of Chicago, is instructive. Burnham’s approach is indicative of many modernist planners in that he envisioned a wholesale re-creation of Chicago, which he illustrated in ways that aestheticized the metropolis rather than grappled with its existing complexities.23 Burnham’s ambitious project married grandiose neoclassical monuments with spacious, axial boulevards that recalled Baron Haussmann’s reinvention of Paris four decades earlier.24 He spared no expense in representing his vision.

He hired seven gifted artists to design the illustrations and even contributed $10,000 of his personal money to the color-printing costs. The final product was impressive. The images plied viewers with fantasies of a unified, neoclassical cityscape punctuated by uncluttered, axial thoroughfares, grand civic centers, and formal gardens and plazas (Figure 2).25

Perkins, on the other hand, visualized the city in purely diagrammatic terms – there are no images of architecture in his proposal. Juxtaposing the forms of representation used by the two architects to illustrate their plans reveals their inimical strategies towards environmental reform. Burnham’s illustrations, while stunning, are more suggestive than definitive. They entirely ignored the modern commercial architecture pioneered in Chicago and flattened the actual variegated cityscape into an imaginary and uniform fabric that served mainly as a backdrop to grand neoclassical gestures. They operate autonomously as art objects first and planning documents second.26

The cartographic strategies that Perkins employed were certainly less seductive, but they shifted the focus of his plan away from utopian idylls of a future Chicago to the physical and social realities of the existing laissez-faire metropolis. His practical solutions, together with the scientific character of his illustrations, imparted an objective and rational quality to his project, which read as a set of empirical facts and actionable suggestions. Diagramming rather than drawing also meant that Perkins relinquished creative control over design specifics.27 His metropolitan plan was a framework rather than a blueprint, and its flexibility was perhaps its most revolutionary feature.

THE CONTINGENT CITY

Perkins championed modest, piecemeal interventions over radical, visionary changes in his metropolitan plan. He believed the gradual construction of neighborhood playgrounds, public schools, and recreation centers would, over time, revitalize local communities and check the abuses of the laissez-faire metropolis. His geographically widespread network of neighborhood centers lacked the drama of Burnham’s centrally located, monumentally conceived civic buildings. However, they were feasible, affordable, and encouraged broad participation by engaging local communities and ordinary people. His network was also flexible. It could accommodate future population growth, since it was organized around dispersed centers rather than a centralized complex. This also meant it could be constructed in phases, one center at a time, with minimal disruption to communities.

Perkins standardized building plans whenever possible to facilitate economical construction - usually completed by others at some future date. He pioneered a “connected group plan” for high schools in which various school functions, such as libraries, auditoriums, and gymnasiums, were housed in distinct annexes (Figure 3).28 This allowed adult members of the community to enter the public spaces of these schools directly. Perkins intended the entire community to use them on weekends and evenings for athletic competitions, meetings, fairs, and lectures that would cultivate local civic engagement.29 Connected group plans were readily expandable, since their loosely connected volumes facilitated the addition of future annexes as student populations expanded and funding increased. When Perkins discussed the architectural design of community centers, he focused exclusively on their plans, not their exterior aesthetics.30 It was programming, public accessibility and public involvement in the design that was of most importance. Consequently, the architectural design of neighborhood centers varied from community to community, depending on local preferences, budgets, and dates of construction. What resulted was a vibrant patchwork of local choices and preferences that together convey the pluralism of democratic society in their messy collision.

The contingent nature of Perkins’s metropolitan plan links him to a broad progressive movement that advanced social change through moderate, evolutionary tactics rather than abrupt revolution. As the modern market economy evolved into a complex web of mutually dependent relationships, progressive reformers came to understand that social relations were likewise reciprocal.31 As Addams wrote, in a democratic country, no higher political or civic life can be achieved except through the masses of people, and so “the good we secure for ourselves is precarious and uncertain…until it is secured for all of us and incorporated into common life.”32 Informing such progressive strategies was a radical theory of knowledge articulated by Dewey and other social psychologists such as William James. According to these pragmatist philosophers, knowledge did not exist a priori according to idealist theory, but was created and perpetually reconstituted through continuous experimentation in the real world – personal choices made under specific cultural conditions that were mutually influential and constantly changing.33 In this scenario, progress is achieved through an ongoing, piecemeal process of questioning, testing, adapting, and testing again.34

Progressivism was, in many ways, the political corollary to pragmatist ethics.35 The theory that individual and social values were mutually determined confirmed progressive faith in the efficacy of social cooperation over individual competition. The belief that cultural values were in flux rather than predetermined rationalized the rejection of Marxism and laissez-faire economics.36 Pragmatist experimentation also mirrored the democratic process, whereby change was achieved through a gradual process of compromise. Progressive reform in the United States was populist and collaborative; reformers were willing to compromise, to embrace multiple, piecemeal solutions and to change course as situations demanded. Pragmatism, in effect, denied fixed and rigid scenarios, which fueled the progressive movement’s optimism that conscientious action could change society.

The theoretical framework offered by pragmatism helps us conceptualize the architectural and political strategies that Perkins employed to advance the cause of social democracy. Perkins spent a considerable amount of energy collecting data, working with nonprofits, organizing interest groups, lobbying government officials, and publishing pamphlets in ways that prefigure contemporary research-based practices and grass-roots activism. The first of these practices began in 1898 when he and Zueblin cofounded the Municipal Science Club.37 He worked closely with Alderman William S. Jackson to convince city officials to establish a municipal department charged with constructing and maintaining public playgrounds around the city. For several years he designed schools for the Board of Education and recreation centers for the Lincoln Park District. He was also a nascent environmentalist, campaigning for two decades to preserve native prairie landscapes around Chicago.38 The protracted battle involved raising public awareness of threatened landscapes through weekend outings called “Prairie Walks,” collaborating with the landscape architect Jens Jensen to conduct and publish environmental surveys, traveling to the capital of Illinois to directly lobby the governor, drafting legislation, and filing lawsuits.39

Perkins and his milieu frequently leveraged technology and the media to advance their goals, recognizing the political power of mass communication and reproducible images. One of the earliest examples was in 1898 when the Municipal Science Club invited the muckraking photojournalist Jacob Riis to give a public lecture on urban and social reform. Riis already had caused a national sensation with his book How the Other Half Lives, in which he documented the child laborers, rag pickers, and squatters that constituted the underbelly of the modern metropolis through experimental flash photography.40 He projected slides of these photographs, still a novel technological process at the time, during his lecture at the Club to substantiate his verbal arguments with emotionally compelling images. The Club, for its part, capitalized on Riis’s celebrity and the afterlife his photographs retained in print media to galvanize public support for its initiatives.

Perkins became a local celebrity himself in 1910 when he orchestrated a highly publicized lawsuit against the Chicago Board of Education in order to expose the political corruption behind such an important public body.41 He lost his case, but not before journalists published scathing accounts of the graft, nepotism, and political favors revealed during testimonies and cartoonists lampooned the Board president by drawing caricatures alluding to his alcoholism.42 Perkins knew the lawsuit would never save his job, but the media coverage generated by the trial was one way to hold corrupt politicians accountable to the public.

Working for decades through public and private channels, Perkins clearly believed in the power of ordinary, private citizens to realize palpable change to the status quo and to “do something” about the challenges confronting modern society. He also recognized the limitations of private philanthropy, arguing that truly public, tax-supported initiatives avoided the paternalistic nature of charity because they “derive their support and authority…from the people themselves.”43 So he worked to institutionalize progressive reforms, to make social change permanent. He understood that public spaces were the backbone of democratic society, and dedicated his architectural practice to creating them for all classes of people. Considering the reactionary postures prevalent today regarding security and surveillance - manifested in the proliferation of “privately owned public spaces” and gated communities - Perkins’s trust in others and his optimism about the democratic process suggests a certain faith in public life that seems forgotten today. Working in the gap between moribund cultural institutions and the public allowed Perkins to revitalize a new civic imagination capable of not just making things, but of making things happen.44

TOWARDS A CONTEMPORARY URBANISM

More than one hundred years after Perkins published his plan for a “contingent city,” we find ourselves in symmetrical territory, as the privatization of resources, global migrations, terrorism, and economic and environmental crises have again created conditions of excessive inequality that our atrophied government, cultural, and urban institutions seem incapable of engaging. These changes have transformed the way space is produced, and accessed, so fundamentally that some critics argue space is the “final frontier of capitalist expansion.”45 The rise in the 1990s of a celebrity architecture culture and a retrenchment into critical theory is symptomatic of the perceived failure of modernism to realize its social mandate. However, in the wake of postmodern aestheticism, a number of architects are working to recuperate something of the lost modernist project, to advance a sense of social responsibility through their design practices using contemporary strategies of engagement.46

This new generation of modernists mediates between local governments, nonprofits, developers, and others in processes that combine architectural, political, and advocacy work - allowing them to design projects uniquely suited to specific communities that embrace both physical and intangible spaces. The self-proclaimed “do-tank,” Elemental, has successfully reconfigured social housing as an entrepreneurial opportunity in Iquique, Chile;47 in Caracas, Venezuela, Urban-Think Tank has been involved in numerous projects such as a cable car system in the overcrowded barrio St. Agustin (Figure 4);48 and in San Diego, California, Teddy Cruz employs a variety of political and architectural strategies to address the needs of Latino immigrants.49

What these contemporary “social entrepreneurs” and Perkins share is a commitment to local communities, a willingness to work within existing political and economic frameworks, and a preference for discreet architectural interventions that together constitute strategies for changing society that are remarkably different to those advanced by modern architects. The large-scale sweeping transformations and utopian futures imagined by twentieth-century visionaries such as Le Corbusier have been replaced by a “radical pragmatism” with transformative potential – a kind of modernism after modernism. In this context, perhaps we can understand Perkins and his milieu as pioneering a kind of modernism “before” modernism with important lessons for contemporary social practices. Perkins understood cities as contested social and political spaces as much as architectural ones. He operated strategically in the liminal spaces of larger cultural constructs rather than attempting to revolutionize them - recognizing that his vision was only one among many. He worked with local and state governments as a public servant and also challenged these institutions from the outside as a private individual.

It should be stressed however, that Perkins’s practice was not an uncomplicated exercise in community building. Public protests, labor disputes, and insufficient funding delayed or impeded many of his projects. Local residents frequently opposed clearing slums to make way for parks or schools because it destroyed their homes and businesses.50 Land speculators looking to maximize profits drove up real-estate prices when the city tried to purchase vacant lots for playgrounds or acquire undeveloped woodlands for public parks. But these struggles could also be read as the contentious, disputatious - one could say democratic - processes of compromise that come with an architecture dedicated to social practice. In following this trajectory, Perkins arguably sacrificed vision for contingent progress. His omission from histories of modern urbanism could, perhaps, be regarded as a sign of his success in this regard – local schools, playgrounds, and community centers are today considered so fundamental to modern cities that we take their existence for granted. His legacy then, although unremarked, is unquestionable. He was a citizen-architect. As the critic Thomas Tallmadge noted when he wrote of Perkins in 1915: “Here in Chicago…we think of him as a citizen and patriot almost before we think of him as an architect; and if we wish thoroughly to appreciate his work, we must regard it in the light of his high ideals of the responsibility and opportunities of citizenship.” His radical pragmatism perhaps offers a model of direct relevance today.