Introduction

The calls for the cultural heritage sector to join other agencies and organisations in taking on the mantle of action towards sustainability and a wider recognition of the importance of engaging with the wider public through various projects and activities that promote the social role and relevance of heritage are intensifying. Since the 1990s co-creation and various types of community participation and collaboration have been employed to facilitate the closer connection between heritage professionals and the various heritage audiences. Within this context, botanical gardens – both as organisations linking natural and cultural heritage and as important actors in efforts to promote food security and sustainability – are well placed to engage actively with their surrounding communities in order to tackle global issues affecting, among other things, food futures.

This article aims to address the potential of participatory approaches and processes of co-creation for fostering effective partnerships through a critical reflection of a series of activities undertaken for the EU-funded BigPicnic project. The methodological processes and approaches underpinning this project will be examined, along with specific examples of exhibitions and science cafés co-created through the work of the botanical garden partners and their communities. This analysis will serve to highlight how community participation can foster forms of knowledge that go beyond the dichotomy between experts and non-experts, and how public views can be truly incorporated in research that addresses topical global challenges.

This article will reflect on the circumstances and discourses that have pushed cultural heritage sector organisations (such as museums and botanical gardens) to assume accountability and greater responsibility for tackling globally significant environmental and societal issues by achieving the goals of the sustainability agenda. The development of the notion of co-creation will be addressed, along with the growing emphasis in the heritage sector on participatory approaches. This is followed by a brief overview of the BigPicnic project, situated in a research framework that fosters public engagement. This article will then proceed to outline the participatory approaches employed in the aforementioned project to engage with the different communities of the botanical garden partners. By presenting some examples of co-created exhibitions and science cafés that resulted from the adoption of the project’s participatory approach, we will be led to a discussion of the potential for co-creation to foster different forms of knowledge and to address sustainable food futures.

It is argued here that museums and heritage organisations can employ participatory approaches not only in their efforts to engage with their communities more successfully but also for potentially achieving insights relevant to wider societal and environmental concerns. The example of the BigPicnic specifically demonstrated that co-creating activities between botanical gardens and their communities can raise awareness not only about more sustainable food futures, but also highlight potential pathways for relevant decision-making and policy change.

Cultural heritage sector organisations in an era of increased accountability and responsibility

In the last decades the role of museums and heritage organisations (henceforth cultural heritage sector organisations) in promoting societal and environmental issues has been widely recognised and promoted on an international level. Very often this is done under the wider remit of supporting the sustainability agenda (McGhie 2019, 2020; ICOMOS 2017; UCLG 2018; ICCROM 2020; UNESCO 2021). There are growing expectations that the cultural heritage sector should encourage dialogue and discussion, and make a meaningful contribution, both individually and collectively, to cultivating a sustainable future. Indeed, at the time of writing this article, the sector is closely following developments in the run up to the 26th United Nations Climate Change conference held in Glasgow (CultureCOP26 2021).

Since at least the 1990s, the belief that cultural heritage organisations hold social responsibility and accountability and should engage in activities that can impact on issues such as social cohesion, justice, equity, inclusion and welfare has also been at the core of both heritage practice and policy (Karp et al. 1992; Sandell 2002; Newman and McLean 1998; Council of Europe 2005; Heritage Alliance 2011; Jones and Leech 2015). Museums, for example, have been at the forefront of an attempt to become responsive to the values, needs and interests of their communities by broadening and diversifying their audiences, embracing community engagement and participation, and undertaking activities that are community-led (Janes and Conaty 2005; Link 2006; Newman 2005; Black 2010; Museums Association 2013; Scott 2013). Making good use of the public or social value of heritage is not a process without challenges (Olivier 2017), but several examples of projects and activities demonstrate the potential of the wider cultural heritage sector to achieve such societal goals (Johnston and Marwood 2017; Kiddey 2018).

On global issues, such as environmental protection and the climate crisis, cultural heritage organisations seem to have acquired an obligation to be leaders in their communities, their countries and globally (AAM 2013; Museums Association 2008; UNESCO 2013). They are considered as showcases for demonstrating what can be achieved in the workplace by ‘going green’ (Brophy and Wylie 2013, Sutton 2015), but they also have the capacity to provide community education on sustainability (Hebda 2007). There are opportunities not only to present complex issues, such as global warming, in displays, activities and publications, but to do so in ways that are inclusive and accessible. Overall, cultural heritage organisations can provide forums for the presentation of new knowledge and debates on important sustainability issues such as reconciliation, poverty, global warming and biodiversity (Koster 2006; Madan 2011; Cameron 2012; Newell et al. 2017). What is more, these organisations can develop partnerships with local communities in sustainability awareness projects for both information sharing and community action (Longoni and Lugalia-Hollon 2012). Despite concerns raised over how unachievable or utopian sustainable development might be (Bushell 2015) and criticism over a lack of concerted action (Janes 2020), the cultural heritage sector should be well placed to press for positive change.

As has been argued elsewhere (Kapelari et al. 2019), food security is one of the greatest global challenges facing our society today. The establishment of the notion of food heritage, such as cultural and traditional food practices, foodways or culinary knowledge, has indicated how food production and consumption, as well as people’s food choices, preferences and behaviour, are directly linked to all of the so-called pillars of sustainable development: environmental, economic, social, cultural. One could therefore claim that the cultural heritage sector’s growing preoccupation with food heritage has created even bigger opportunities for heritage organisations to address environmental sustainability from the perspective of food security. Certainly this has been underpinned, on a practical/organisational level, by the recognition of food as a form of intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO (Di Giovine and Brulotte 2014) and, on an academic level, by the ‘heritage turn’ in food studies (Demossier 2016) and the growing interest in food heritage within heritage studies (Alexopoulos et al. forthcoming).

Within this context, botanical gardens – which will be at the centre of this article’s case study – are uniquely situated to undertake the responsibility of promoting sustainability through food heritage. They can be considered important members of the wider cultural heritage sector, as informal educational institutions, research centres, contributors to plant conservation and places that not only contain museums and/or hold and display significant collections but also link natural and cultural heritage (Dodd and Jones 2010; Kapelari 2015). A very effective way of maintaining accountability and responsibility for tackling global problems, as will be argued in the following section, is through embracing participatory approaches that employ co-creation in an effort to work closely with communities and other stakeholders.

Co-creation in the heritage sector as a result of changing discourses and the adoption of participatory approaches

Co-created activities in the context of heritage organisations have come about as a result of several decades of experimentation and application of collaborative practices and participatory approaches. Very broadly, the term co-creation means ‘working with our audiences (both existing and new) to create something together’ (Govier 2009, 9). In the context of museums and heritage attractions the term appears to borrow notions from Sherry Arnstein’s (1969) ‘Ladder of Participation’, which articulated a model for the power and involvement of citizens in planning projects. This model has been employed and slightly modified in guides for managing effective participation (Wilcox 2003; HLF 2010). Other models implemented in the museum and gallery sector specifically have adapted elements of Augusto Boal’s participatory drama concept; they have also been underpinned by the principles of Participatory Action Research (Lynch 2011, 24–5).

Meanwhile developments in the academic field of heritage studies and the practice of cultural heritage management have also contributed to the embracing of participatory approaches towards the wider public. Calls for a re-theorisation of heritage (Smith 2006) and the adoption of new approaches have supported the movement of critical heritage studies in order to, among other things, bring forward ‘the interests of the marginalised and excluded’ (ACHS 2012). Inevitably such conceptualisations have promoted the perceived democratisation of heritage that goes hand in hand with the increasing concern for participatory approaches. This has been described as a ‘democratic turn’ (Hølleland and Skrede 2019, 827) in heritage studies and refers to developments in the relationship between experts and non-experts and the current emphasis on participatory decision-making processes (Harrison 2013, 223–4; Schofield 2014). Of course, this direction has not emerged in a vacuum; it has also been supported by the emergence of social media that fosters the notion of participatory culture (Jenkins et al. 2006; Giaccardi 2012). Discourses on values-based heritage management, however, have emphasised the necessity of promoting public participation and bottom-up (rather than top-down) decision-making processes (Millar 2006; Wijesuriya et al. 2017). What is more, the work of political economists, such as Elinor Ostrom, who have promoted the notion of the commons – where the public or the community are made up of responsible citizens – has inspired discussions of the potential of a ‘heritage of the commons’ (Lekakis 2020).

Furthermore, notions from citizen science have also inspired various participation models that have been employed in the cultural heritage sector context. Citizen science, developed in the 1990s (Irwin 1995), constitutes an ‘umbrella’ term that describes processes in which ordinary citizens are actively involved in science research, collaborating with the ‘experts’ and contributing to a specific outcome, such as new scientific knowledge (Hand 2010; Kullenberg and Kasperowski 2016). Strongly supported by the European Commission (2014), citizen science has formulated a clear set of principles with museum practitioners having a leading role (ECSA 2015; Hetland et al. 2020).

The model of the PPSR (Public Participation in Scientific Research) project defined three broad categories of public participation in scientific research: ‘contribution’, ‘collaboration’ and ‘co-creation’ (Simon 2010, 183–7). To these three categories American museum director Nina Simon presented, in her seminal publication The Participatory Museum, a fourth type of visitor participation in museums: that of ‘hosting’ (Simon 2010, 281–95). According to Simon, co-creation happens when the institution works closely together with community partners from the start to define the project’s goals, which have to be shared. The result is a project which is truly co-owned by both (Simon 2010, 262–3). Co-creative projects are therefore based on a recognition and development of both community and institutional needs (Simon 2010, 263).

Co-creation implies the active involvement of people outside the heritage organisation – who become agents of co-creation – in the production of activities of any sort (Haviland 2017a; Robinson 2017; Shaw et al. 2021). In the case of the preparation of exhibitions, for example, museums may engage with external actors who are given significant creative agency, resulting in ‘co-curation’, ‘co-production’ or ‘co-design’ processes (Davies 2010; Mygind et al. 2015; Barnes and McPherson 2019; Popoli and Derda 2021). Although not all of these terms have the same meaning, and there may sometimes be a lack in clarity with regard to their use (Govier 2009, 3), these terms have been applied to describe a variety of projects. As Haviland (2017b, 886) points out, ‘expectations of collaborative processes can run high, but in reality are often partial, contingent or frustrated by the multiple constraining factors of on the ground implementation’. Despite the challenges and potential shortcomings in the actual implementation of such processes, the end result can enable cultural heritage organisations to tackle global problems with the help of their communities.

It is useful to conclude this section with a reference to the close ties between the notion of co-creation and Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI). The latter has recently emerged as a science policy framework aiming to engage members of the public in the production of ethically acceptable, sustainable and socially desirable research and innovation outcomes (RRI Practice 2021). European Union-funded projects have therefore situated the notion of RRI in the co-creation domain. RRI has focused on how co-creation and design knowledge and tools can be applied to engage citizens in shaping more inclusive, responsible and sustainable solutions (Deserti and Rizzo 2022, 1). The example of the BigPicnic project, presented in the following sections, is very relevant in this context as it was funded by the European Union’s research and innovation programme, Horizon 2020.

The BigPicnic project

The BigPicnic project (full project title: ‘Big Picnic: Big Questions – engaging the public with Responsible Research and Innovation on food security’) was undertaken between May 2016 and April 2019. It was funded by the European Commission’s Horizon 2020 programme (BigPicnic 2021). For the purposes of the project a consortium of 19 partners was brought together, including 15 botanical garden partners, the Botanical Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), two universities (UCL and the University of Innsbruck) and a research laboratory for technology and society (WAAG). The botanical garden partners consisted of 14 European organisations and one from Uganda. 1 The aim of the project was for the partners to engage actively with a range of audiences and communities to co-create a series of outreach exhibitions, science cafés and other activities that would address food security issues (BigPicnic 2021).

It was anticipated that this form of synergy would facilitate interaction and dialogue between various stakeholders, bridge the gap among the public, policymakers and researchers, and create the opportunity to build a greater understanding of topical issues surrounding the present and future of food systems. A further objective on an organisational level was to ‘build the capacity of botanic gardens across Europe to develop and deliver co-creation approaches with their local and regional audiences’ (BigPicnic 2021). Serving as a key feature of the ‘Science with and for Society’ objective of the Horizon 2020 programme (European Commission 2021), the BigPicnic project sought to voice the concerns and ideas of citizens on the issues that underpin RRI. In addition, it aimed to disseminate the outcomes to policymakers that influence and implement decision-making for food security (BigPicnic Management Board 2019, 23–37).

The project partners organised more than 100 outreach exhibitions; they reached over 180,000 people and created more than 100 science cafés, with a total of around 6,000 participants. The project culminated in the BigPicnic Final Festival that took place on 27 February 2019 at Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid in Spain. This event not only served to launch the recommendations and policy briefs developed by the Management Board, but also brought together educators, policymakers and other stakeholders to participate in workshops, discussions, presentations and exhibitions that highlighted the outcomes of the project.

The information about the BigPicnic co-creation projects, presented in the following sections, draws on the experience of the authors in working for the project management board and the project evaluation team. It also relies on several of the project deliverables, as well as the qualitative and qualitative research that underpinned the latter. The qualitative data, on the one hand, consisted not only of studies carried out by the botanical garden partners throughout the co-creation activities, but also of a large-scale survey with 1,189 respondents (Kapelari et al. 2020). The qualitative data, on the other, are based on a meta-analysis of the findings from 76 reports compiled by the 15 botanical garden partners. These reports reflected on the results of observations, interviews, focus groups and various other methods that the partners employed following the Team-Based Inquiry (TBI) evaluation framework.

Participatory engagement at the BigPicnic project

‘Co-creation’ has been employed by various cultural heritage organisations in a variety of contexts and projects; it has also been inspired and shaped by a range of discourses, ethical principles and models of practice. The BigPicnic consortium adopted its approach on co-creation in line with the European Commission’s objectives for RRI and the participatory engagement was based on the employment of both co-creation and TBI. The aim was to engage multiple publics with food security issues by offering entertaining, interesting and relevant/targeted activities through the co-created outreach exhibitions and the science cafés (BigPicnic Management Board 2019, 11). Reflecting on the methodological approach of the BigPicnic project, it is important to underline some aspects of RRI, co-creation and TBI that were crucial in the implementation of the project activities.

Responsible research and innovation

RRI, as has already been stressed, emerged as a science policy framework in Europe with a particular connection to the notion of co-creation. At the same time, the agenda promoted by RRI has pressed towards the identification of solutions for the sustainability of food production and food processing systems with a particular concern for environmental impact and societal value (BigPicnic Management Board 2019, 8). This direction is directly underpinned by the European Commission’s six policy agendas for RRI: Ethics, Open Access, Gender Equality, Public Engagement, Governance and Science Education (RRI Tools 2021). As highlighted by its Management Board, the BigPicnic project’s ideology and approaches have supported RRI in food security. More specifically, they have embodied what RRI has identified as inclusive innovation, multi-actor approaches and a wider cross-fertilisation of interactions between diverse and significant stakeholders (for example, researchers, businesses, farmers/producers, advisers and members of the public affected by food security issues) (BigPicnic Management Board 2019, 8). BigPicnic achieved not only the creation of an environment, within the botanical garden partners, for undertaking co-creation activities, it also showed how to use these in order to generate knowledge, expertise and opinions derived from a broad range of stakeholders. This feedback was crucial in turn for generating recommendations disseminated to the higher echelons of power, in the hope of achieving policy changes for food futures. The employment of co-creation approaches and the TBI participatory evaluation process was paramount in achieving this.

Co-creation

We mentioned earlier that in the cultural heritage sector co-creation is often summed up as the process of ‘working with our audiences to create something together’ (Govier 2009, 9), and this is exactly what the BigPicnic project advocated. The WAAG project partner, responsible for the training of the botanical gardens in co-creation and participatory approaches, emphasised that the aim of co-creation is to ‘create shared values in collaboration with communities’ (Wippoo and van Dijk 2019, 6). The methods employed begin with the idea that everyone is an expert on their own life and potentially on other issues affecting it, a conviction that echoes the principles of citizen science and indicates similarities to the recent discourses on critical heritage studies. The views, values and concerns of the members of the public who participated in the co-creation groups correspond to a different level of expertise (equally valuable in the co-creation process) to the expertise provided by scientists, food industry representatives and other ‘food experts’. As in the critique raised by Sherry Arnstein’s ‘Ladder of Participation’ and Nina Simon’s ‘Participatory Museum’, decisions should not be made by one single participant group – but neither should there be a process of mere consultation of the public on the part of the groups that constitute the professionals or experts on the subject. All participants build a relationship and engage in a dialogue where the exchange of ideas and values is absolutely vital (Wippoo and van Dijk 2019, 6). Furthermore, co-creation requires a creative and interactive process that should not shy away from challenging, in a constructive manner, the views of all parties in the co-creation group, as well as seeking to combine the different types of expertise in new ways.

The co-creation design process manages to connect: [1] relevance, by involving experts and the existing scientific knowledge in themes that are relevant to all parties; [2] ownership, by allowing people to feel that they have contributed to the creation of something; [3] agency, by showing people clearly what their options and solutions are and encouraging informed decisions; and [4] sustainability, by enabling the ideal and most durable design options to emerge from processes of testing and experimentation (Wippoo and van Dijk 2019, 6). Just as cultural heritage organisations need more bottom-up processes truly to provide community participation in heritage decision-making, so the BigPicnic approach to co-creation advocated for botanical gardens to allow the freedom and possibility for the project to change course if needed. In many cases adopting co-creation by the organisation in question may also require a certain degree of organisational change, or at least flexibility in the operation of the organisational structure (Wippoo and van Dijk 2019, 6). Ideally the co-creation process should foster relationships between the botanical gardens that will last well beyond the confines of the project itself (BigPicnic 2021).

In order to improve the understanding and realisation of RRI through the provision of best practice case studies, a toolkit was developed. This served as a resource to support the adoption of the co-creation process and the project’s participatory approaches (Wippoo and van Dijk 2019), along with an online co-creation navigator (WAAG 2021).

Team-based inquiry

Throughout the co-creation process described above, the botanical garden partners were trained and guided in the use of TBI. This is a form of action evaluation designed to assist practitioners and other stakeholders to define and evaluate project effectiveness and to achieve effective action/practice (Pattison et al. 2014). This participatory evaluation framework was employed to ensure the activities were delivered to the highest possible standard. It also helped to record and analyse the interactions generated from the various BigPicnic activities and events. The framework was also selected for its suitability in offering botanic garden practitioners a tool to evaluate their projects and reflect on their practice – a key aspect of this process being that evaluation was undertaken by the botanical gardens themselves rather than by an external consultant (Moussouri et al. 2019). Of course, this was also an evaluation process that aimed at giving practitioners skills they can employ in their future work beyond the BigPicnic activities.

Overall, TBI consists of a four-stage cycle: question, investigate, reflect and improve. Stage 1 (‘question’) serves to identify the inquiry questions, and Stage 2 (‘investigate’) requires the selection and formulation of appropriate methods to answer these questions and then collect the data to investigate them (Moussouri et al. 2019). Stage 3 (‘reflect’) includes analysis of the data, which ideally should be a process of teamwork, while Stage 4 (‘improve’) consists of an attempt to use the findings in order to improve the evaluated activities (Moussouri et al. 2019). A sample of 76 TBI reports completed by the project partners served as the basis for compiling recommendations and policy briefs with the aim of supporting the principles of RRI and of informing decision-making for food and food security (BigPicnic Management Board 2019). One of the useful deliverables of the BigPicnic project was indeed the creation of a concise and well-illustrated guide for TBI (Moussouri et al. 2019).

Co-creating sustainable food futures with communities: some BigPicnic examples

Co-creating outreach exhibitions

The BigPicnic project partners co-created more than 100 outreach exhibitions on the wider subject of food security. The term ‘exhibition’ was used in a flexible manner to incorporate activities and events that went beyond the traditional understanding of the term (for example, public display of information, objects and materials in panels or glass cases) to include also workshops, demonstrations in various formats and practical, hands-on activities. This was a deliberate choice that enabled the co-creation teams to employ creativity and innovation in achieving their goals (BigPicnic Project Consortium 2019).

Each partner initially identified certain ‘hard-to-reach’ audiences to engage with on the subject of food security. These audiences represented a vast array of groups, including diaspora communities, families and schoolchildren, socially and economically disadvantaged people of various ages, senior citizens and people involved in the food industry in various capacities (for example, farmers, food activists, entrepreneurs) to name but a few. The process involved working closely with representatives from these communities in both the development of the ideas and the selection of exhibition materials. The themes selected for the outreach exhibitions were also wide-ranging, with the co-creation groups deciding together on what to address. The following are a few of the themes tackled: food and sustainability, food waste, climate change, pollination, biodiversity, urban gardening and the cultural aspects of food. The outreach exhibition venues included a variety of locations to ensure that the project’s reach was as wide as possible: it encompassed indoor and outdoor spaces both inside and outside the botanical gardens in question. What follows is a presentation of three examples of outreach exhibitions undertaken by the BigPicnic partners in the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom.

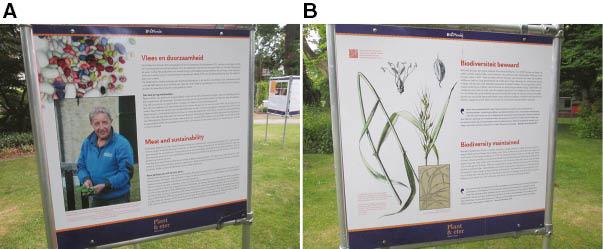

The Hortus botanicus Leiden in the Netherlands, founded in 1590, belongs to the University of Leiden. It decided to collaborate with its audiences in an attempt to discover more about the edible plants within its collection, seeking to encourage more conscious decisions about plant consumption and issues of sustainability. A co-created exhibition titled Plant-eater was prepared, extending around the botanical garden’s outdoor area. The exhibition, which took place from April to October 2018, presented stories about both well-known and less well-known food crops, their origins and use and a variety of facts (for example, biodiversity, meat consumption, carbon footprint of food transport and so on). A separate route was designed for children aged between 8 and 12, and there were several plant- and food-themed games for families and children throughout the botanical garden. The opening of the exhibition was also accompanied by the preparation of a cookery book with eight Hortus soup recipes (featuring ingredients from food crops available in the botanical garden, with some of the relevant dishes also being available at the café-restaurant), as well as a book about plants and personal health (Hortus Leiden 2021). Some of the stories and facts collected and presented in the exhibition panels (Figures 1 and 2) were incorporated into a richly illustrated card game (available for free to all paying visitors); the game aimed not only to entertain both children and adults, but also to create links with the exhibition’s information and themes. All of the above mentioned content resulted not only from expert knowledge, but also from a series of activities and data collection processes that preceded the creation of the exhibition and addressed the public’s views on, and knowledge about, edible plants.

(A) Information panel addressing ‘Meat and Sustainability’ from the Plant-eater exhibition held at Hortus botanicus Leiden; (B) Information panel addressing the issue of biodiversity from the same exhibition (Source: photographs by Georgios Alexopoulos)

(A) General view of rotating information panels from the Plant-eater exhibition at Hortus botanicus Leiden; (B) A view of the text available for children on a rotating four-sided panel from the same exhibition (Source: photographs by Georgios Alexopoulos)

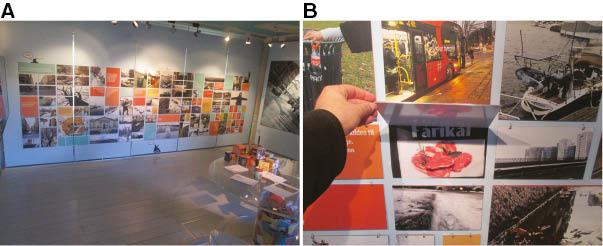

The Natural History Museum of the University of Oslo (UiO), Norway, organised an exhibition that ran from April to December 2018 titled The Future Is Now – Young People’s Views on Climate and Food in a Time of Climate Change. This was the result of a co-creation process that aimed to explore and present what young people saw and thought of and understood by climate change and its impact on food-related issues. Prior to the launching of the exhibition, the co-creation process aimed at collaborating with students from six high school classes (aged between 16 and 17). The students were asked to work in small groups and take pictures with their mobile phones, then to write brief texts to accompany these images (Figure 3). The idea behind the images was to reflect on how their food habits contribute to climate change and how climate change can affect their food supplies. Images covered a range of issues such as the high price of food at the supermarkets, the extensive consumption of meat, the reliance on imported food from distant countries and so on. Some of the students were interviewed for a short film that was subsequently displayed in the exhibition space. The students were given significant freedom in the choice of the images and were assisted in the practicalities required to prepare the display. This was the first time that the UiO (2021) project partner had an opportunity to engage with this specific type of young audience and the feedback gained was taken into consideration by the team planning the Climate House, which opened in summer 2020.

(A) A general view of the exhibition at the botanical garden of the Natural History Museum of Oslo; (B) A closer look at the images displayed (Source: photographs by Georgios Alexopoulos)

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) in Scotland engaged with the barriers that certain members of the public encounter in their attempt to access nutritious food. The subsequent activities developed by RBGE and its co-creation groups provided very interesting insights into how various types of inequality, food cultures and knowledge about food influence eating habits and reinforce such barriers. As part of this effort the RBGE (2021) collaborated with local food initiatives such as Pilton Community Health Project, Crisis Scotland, Wellhouse Allotments Society and Bridgend Inspiring Growth. The aim of this collaboration was to give voice to individuals who could share their experiences and challenges. Digital storytelling, a video-making method, was employed for the purpose of training participants to use relatively simple equipment and software in order to develop and record personal food stories; no prior experience was required. The RBGE partner observed that this method worked well for small groups (of up to six people), enabling each person to create their own story of two to three minutes duration. The digital stories eventually took the form of an audio track supported by still images; the great strength of the format was the emotional power of these personal stories.

The digital stories also provided ideal material to stimulate discussions with people participating at subsequent events and venues. The project partners also employed pop-up exhibitions that were easy to move from one venue to another (for a selection of digital stories, see RBGE 2021). Listening to the different stories, including the challenges faced by immigrants in Scotland to satisfy their dietary needs, people coping with a vegetarian diet or the food habits of family members with autism, it becomes clear that people can change their relationship with food when they create a personal story about food and reflect on their personal situation. On 16 January 2019 the 19 food stories created were presented to an event at the Scottish Parliament, attended by many of the stories’ creators. This was seen as a powerful way of bringing into the spotlight the voices and stories of often marginalised people, and to touch on important food security issues (Coleman 2019).

Co-creation and science cafés

Inspired by the so-called Café Philosophique movement in 1990s France, science cafés were first created in the UK as a medium that could foster better connections between non-scientists and scientists. The intention was to render science more accessible to the general public in a relaxed and informal setting that nevertheless encouraged debate and the exchange of ideas. Today science cafés exist in many countries around the world. They serve to connect different stakeholders and create an atmosphere in which all participants feel encouraged to listen to others and to share their thoughts (Kapelari et al. 2019). The choice of the venue is important as it may influence the level of comfort felt by audiences that do not usually get involved in science and scientific discussions. The experience gained by the BigPicnic project partners was very valuable. It culminated in a relevant toolkit for the development of science cafés that offers details on issues such as what counts as a good topic to address or who are the ones to take part (Kapelari et al. 2019).

To produce this toolkit, the authors relied on a careful consideration of the co-creation processes for the selection of science café topics and on the application of the TBI evaluation process (and the resulting reports) to these science cafés. Science cafés are very suited to the citizen science movement which has, as already indicated, gained significant momentum in the 2010s; they offer a type of event that could be adopted more widely by organisations from the cultural heritage sector (not only confined to science or natural history museums, already very active in this area). The following are some observations of interesting ways in which science cafés were developed for the BigPicnic project not only for employing co-creation approaches, but also for fostering useful interactions between experts and non-experts on sustainable food futures.

Most of the BigPicnic partners employed science cafés to collect data and ideas for the subsequent development of exhibitions on food security. Ideas and feedback received during the science cafés were utilised to inform other activities.

In some cases practitioners rather than scientists and academics were selected to act as a bridge between scientists and other participants. Such groups included, for example, bakers, farmers, chefs, activists and members of diaspora communities. As mentioned in the relevant toolkit (Kapelari et al. 2019), even children can become ‘experts’ when the debates under discussion relate to decision-making in schools.

The cultural aspects of food, and the relevance of food production and consumption to eating habits, traditions, memories and identity formation, were matters more easily addressed when audiences included people from various ethnic, religious and social backgrounds, as well as a wider range of age groups. Sometimes solutions to burning contemporary problems were based on traditional forms of knowledge rather than purely scientific knowledge.

Inviting speakers and contributors who represent opposite sides of hotly debated or controversial issues surrounding food sustainability can offer a broader view of the problems and concerns facing not only the scientific community but also the wider public, who need to make individual decisions on the basis of available and reliable information.

Discussion

This article has demonstrated how several ideological developments and discourses have pushed cultural heritage sector organisations to become more accountable and responsible in their day-to-day operations and activities, and actively to promote the goals of sustainable development. It has been argued that wider environmental and societal issues such as food security and the role of food heritage in the wellbeing of future food systems are more effectively tackled when heritage professionals collaborate with their audiences. Participatory approaches and the notion of co-creation are well suited to assist in such efforts. The example of the BigPicnic was discussed as an interesting example of a project underpinned by a robust methodological framework to deliver its objectives that relied on RRI and employed co-creation and TBI for effective engagement of all participants.

Citizen engagement activities that are co-created rather than strictly expert-led provide opportunities for the public to raise their voices. The voices of these different communities in turn can offer important insights into the ongoing efforts to tackle global challenges such as the achievement of the sustainability goals. In the case of the BigPicnic project, the concerns and views of the communities of the botanical gardens were projected through the co-created activities that addressed food security. This process highlighted the need for future food policies to incorporate greater awareness of public attitudes and opinions about food. Overall, the co-created activities undertaken for the BigPicnic led to a greater understanding of how food is embedded in every aspect of people’s lives. Furthermore, what the project partners experienced first-hand was that citizens need to feel that they can help co-create sustainable food futures, rather than merely being consulted.

Both co-created outreach exhibitions and co-created science cafés have the potential to constitute effective, interactive vehicles for engaging informally with different communities and discussing topics relating to food security. Indeed, the co-creation activities shaped the development of science cafés and vice versa. Following principles and models, such as those of citizen science, the cultural heritage sector could look more extensively to such approaches in order to close the gap between experts and non-experts and to open up a more fruitful dialogue that considers different forms of knowledge (for example, traditional and cultural knowledge as opposed to scientific) without necessarily disregarding one side or the other.

Another interesting outcome of the BigPicnic project that underlines how important it is for heritage organisations, including museum and botanical gardens, to work closely with their public, and to foster different forms of knowledge that go beyond the expert–non-expert dichotomy, is the emergence of the notion of food heritage as a decisive factor in the relationship that citizens have with food. The recognition of the wider impact of food heritage through the project outcomes resulted in the formulation of a specific policy recommendation. What became evident was that discussions surrounding the sustainability of food systems, as well as any relevant decisions and future policies, should carefully consider the cultural and social values attributed by people to food and how the latter impacts on their food behaviour and choices.

The employment of co-creation and participatory impact assessment techniques can facilitate the involvement of communities in voicing their concerns and potentially influencing decisions that promote a sustainable food system. Both the BigPicnic outreach exhibitions and the science cafés empowered audiences that are usually marginalised or not truly listened to in debates about food futures. In some cases, citizens who participated in the project experienced a bigger impact in their lives. In the RBGE’s project, for example, citizens who participated in co-created activities turned from being mere participants into food activists. By acting as mediators, the botanic gardens involved in the BigPicnic (2021) project managed to facilitate dialogue and develop a mutual understanding among researchers and other members of the co-creation teams of the ways in which different people work and think. This guiding principle of all parties working closely to create something together is the important underlying ethos of co-creation.