Introduction

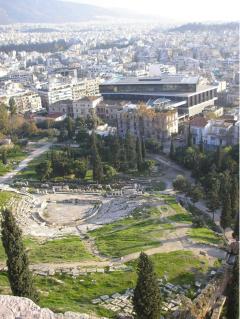

It is almost half-a-dozen years since the New Acropolis Museum in Athens was inaugurated in June 2009, following a gestation period of over three decades (Figs 1, 2). Before, during and after the construction of the building, the importance of natural light was frequently emphasised by the Museum’s Swiss-French architect, Bernard Tschumi, as well as many Greek government officials, archaeologists, and other heritage professionals. The manner in which the same bright sunlight illuminates both the Parthenon and the temple’s decorative sculptures which are now on display in the Museum, is also routinely referenced by campaigners advocating a return of those sculptures that were removed from the Athenian Acropolis on the orders of Lord Elgin between 1801–03 and subsequently shipped to London. Following the purchase of the collection by the British government in 1816, the Marbles of the Elgin Collection were presented to the British Museum, where they are presently on display in Room 18, the Duveen Gallery (Fig 3).1 However, for more than two centuries it has been maintained that the sculptures can only be truly appreciated when viewed in the natural light of Athens. Even before the completion of the New Acropolis Museum there were bitter attacks on the manner in which the Marbles are displayed in the British Museum, and the quality of the illumination afforded to the sculptures in the Duveen Gallery. The aesthetics of the Attic light has therefore taken its place as one of the principal weapons in the armoury of Greek officials and international campaigners seeking the return of the Marbles removed by Lord Elgin. Nonetheless, this paper will argue against the accepted orthodoxy that the New Acropolis Museum replicates the original light conditions many of the sculptures from the temple experienced when on the Parthenon. Indeed, this article will dispute the goal of many architects, politicians, and heritage professionals of the need ensure that, when on public display, all of the Parthenon sculptures are bathed in bright natural light. The ability to display the Marbles in the sun-drenched gallery of the New Acropolis Museum forges a powerful emotive link that binds the environment of Classical Athens with that of the present-day capital of Greece, offering politicians and activists seeking the repatriation of the Elgin Marbles a potent weapon that has been wielded to great effect. However, the politically motivated design parameters laid on the New Acropolis Museum, with one of the primary requirements dictating that the building admit natural vast amounts of natural Attic light into the galleries, has destroyed the architectural context within which many of the Marbles were displayed when originally affixed to the temple in the fifth century BC.

Two Centuries Spent Embracing Natural Light

The natural light of Athens has long been regarded as an important factor in appreciating the Parthenon and the other ancient monuments which crown the summit of the Acropolis. The environmental, and indeed meteorological context of the temple, offer powerful and emotive arguments in favour of returning the Marbles to Athens. Campaigners seeking the repatriation of the sculptures from London have therefore made frequent reference to the cloudless skies that, it is claimed, produce a ‘unique Attic light’.2 Less than a decade after the Marbles were transported to England, Lord Byron offered poetic appreciation of the sunlight of Athens, comparing the conditions to the frequently overcast skies of Britain where the sculptures purchased by Elgin were now to be found. Thus, at the start of the Curse of Minerva (1811), Byron launched a scathing attack on the removal of the Marbles by his fellow Scottish aristocrat, and their transportation to a city above which leaden skies frequently obscured sunlight:

Almost a century later, Thomas Hardy would pen Christmas in the Elgin Room (1905) in which he would emphasise the cold, shadowed nature of the galleries of the British Museum and the weak sunlight of London compared to that in the original home of the Marbles:

‘Oh it is sad now we are sold –

We gods! for Borean people’s gold,

And brought to the gloom,

Of this gaunt room,

Which sunlight shuns, and sweet Aurore but enters cold.’

Since Byron and Hardy there have been numerous calls for the return of the sculptures to Athens so that they might be appreciated under the caress of natural Greek light. Melina Mercouri, the actress-turnedpolitician, who became Hellenic Minister of Culture in October 1981, also referenced the Athenian light in her effort to bolster Greek claims for repatriation of the sculptures. During her address at the World Conference on Cultural Policies, a meeting organised under the aegis of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and staged in Mexico City in July 1982 with Culture Ministers from around the world in attendance, Mercouri put forward the case for repatriation of the Marbles, beginning her speech, ‘As I left Greece, looking down at the Attic sun through the window of my plane at the remains of the Parthenon,’ while she would go on to quote the Greek poet Yannis Ritsos, who Mercouri claimed, ‘expressed the sentiment of all of our people when he wrote: “These stones cannot make do with less sky.” I think that the time has come for these marbles to come back to the blue sky of Attica, to their natural space, to the place where they will be a structural and functional part of a unique whole.’3

In the three decades since Mercouri’s address at Mexico City, the unique (though usually indefinable) qualities of the natural light of Athens have become a major part of the emotional rhetoric attached to the Marbles: only when the sculptures are bathed in the sunlight of Attica, where they were originally carved, can they truly be considered at home. It has been thus been noted that the frequent references to the manner in which the natural light of Athens is regarded as a necessary factor when it comes to appreciating the art and architecture of the city’s ancient monuments ‘pay homage to environmental determinism, a celebrated offspring of German nationalism, according to which culture and climate are organically tied. Transplanted to Greece in the late nineteenth century, environmentalist theories were used to promote Greek exceptionalism as well as champion Greek emancipation from an “unnatural” modernity imposed by the West.’4

Mercouri’s address to the delegates at Mexico City, and her subsequent campaign to reclaim the Marbles from the British Museum, would rouse public sentiment both in Greece and among the world-wide Hellenic diaspora. Indeed, beginning with Mercouri’s tenure as Greek Culture Minister, ‘The question of the return of the marbles dominated the agenda of the Ministry, and attracted public attention up until the inauguration of the New Acropolis Museum.’5 The campaign for the return of the Elgin Marbles has thus become a major component in the cultural and indeed foreign policy objectives of Greek governments since the 1980s, while it has been emphasized: ‘All political parties, from the ultra-nationalist to the Communist, participate in the national crusade for the restitution of the sculptures. Since the affair has become a “national issue” it has been sacralized and is beyond any serious criticism … The crusade also confers authority on the Minister for Culture, who is seen as advancing one of the most important national issues of her/his time.’6

The cultural significance of the Marbles, together with the nationalistic sentiment associated with the campaign to recover the stones in the British Museum, has led to the sculptures being regarded as symbolic capital that have been ‘singularized and commoditized’.7 Such commoditization of the sculptures that originally adorned the Parthenon also touches on the financial rewards that derive from ownership of the Elgin Marbles. John Henry Merryman, a lawyer specialising in cultural property, has therefore noted: ‘Economically, whoever has any of the Parthenon Marbles has something of great value. … [T]he presence of the Marbles in a public collection nourishes the tourist industry. Possession is obviously necessary in order to exploit that kind of economic value.’8 The archaeologist Morag Kersel has also drawn attention to the economic benefits that potentially accompany ownership of Elgin’s disputed trophies, asking the question: ‘Is Greece requesting the Marbles under the guise of nationalism, when perhaps their immediate motives are of an economic nature?9 If the New Acropolis Museum could help bring about the return of the Elgin Marbles to Athens, then the €129 million spent constructing the building might be regarded as an astute long-term financial investment by the Greek state.10

A Museum of Light

The dream of bringing the Elgin Marbles back to Athens and placing them back on the Parthenon, where they might once again become a ‘structural and functional’ part of the temple as was claimed by Mercouri in Mexico City, was, however, quickly abandoned when it was decided that all the decorative Marbles of the Parthenon that remained in Greek hands (many of which were still on the monument despite the destruction being caused to them by the atmospheric pollution of Athens), were to be removed and placed on display in a purpose-built museum. Nonetheless, the claim that the sculptures could only be truly appreciated in the natural light of Athens had become a powerfully emotive clarion call in support of repatriation of the sculptures that had been taken by Elgin and, as such, would not be willingly set aside. As such, when the third architectural competition (and the first open to non-Greek architects) for a New Acropolis Museum was announced in 1989, following two earlier competitions staged in 1976 and 1979,11 the design programme placed great emphasis on the cloudless skies and bright natural light commonly associated with Athens: ‘The mild climate and Attic sky, famous for its clarity of crystal-clear “Attic Light”, complemented the natural harmony of the area.’12 Mari Lending has therefore emphasised the manner in which the natural light of Athens has allowed the Greek government to retain the argument that a return of the sculptures would allow for a context-specific understanding of the Elgin Marbles, regardless of their amputation from the ancient temple:

‘While the argument is cultural, what it sustains is derived from nature. Invocation of the Attic Light places the ambition for the museum within a romantic place-specificity that encompasses architecture’s geographical dependency and climatic component, with an important source in Montesquieu’s theory of climate as elaborated in L’Esprit des Lois (1748). … The reference to the Attic Light, which almost 2,500 years ago enveloped a structure that was later disassembled into historical ‘exhibits’, accentuates an a-historical permanence for the otherwise historically charged structure. Copies have long ago replaced the sculptural elements from the Acropolis in order to avoid the effects of air pollution. The recontextualisation rests on a staging of the objects in a setting defined exactly by the natural lighting conditions, not by their exact original positions.’13

Although the architectural context of the sculptures would effectively be lost by the removal of the Marbles from the ancient temple and their display inside the planned New Acropolis Museum, nonetheless, through reference to the climatic and environmental conditions of Athens – especially the natural Attic light – the 1989 design competition for the Museum retained the claim that the Greek capital offered a unique environmental context in which to appreciate the Marbles. Only in the natural light of Athens, which had illuminated the Marbles for more than two millennia and in which the Parthenon had been fashioned, could visitors see the sculptures as Phidias and the rest of their fifth century creators had originally intended.

Attempts to equate the light conditions – and indeed the wider climatic conditions – of Classical Athens with those of the present-day, are, however, fraught with difficulties. Greece, like the rest of Europe, has experienced a number of climatic changes over the course of the last 2,500 years, bringing with them variations in meteorological and light conditions. Furthermore, the prevailing climate of Athens during the fifth century BC is also currently uncertain and it may be that the Parthenon – and its marble decoration – was created under rather different conditions than those which exist today.14 What can be confidently stated, however, is that from the late 1960s through until the 1990s, Athens was frequently blanketed with clouds stained brown with pollution, while particles of sulphur dioxide (SO2), carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and other compounds emitted from the congested Athenian traffic or industrial processes, were also lingering above the city as aerosols, affecting the health of the population and indeed eroding the marble of the Parthenon and the other ancient monuments exposed to the Athenian atmosphere. Such pollution also affected the natural light of Athens as aerosols both scattered and absorbed sunlight, altering the quality and intensity of light reaching the surface. Thus, at the time when Mercouri was referencing the quality of the Athenian sky in her address in Mexico City in 1982, and when the Greek government was referencing the ‘clarity of crystal-clear “Attic Light”’ in the programme for the third design competition for the New Acropolis Museum in 1989, the Greek capital was at its most polluted. From the very outset, one of the key concepts underpinning the design of the New Acropolis Museum was arguably compromised from an inaccurate and misguided understanding of the climatic and light conditions that existed in ancient Athens relative to those of the present.15

In the end, nothing came of the 1989 architectural competition and a fourth and final contest was held in 2000. Unfortunately, the programme for this last contest has never been released to the public;16 it is, therefore, currently impossible to determine the extent to which its architectural brief stipulated the requirement that natural light was to play a leading role in the design of the Museum. Nonetheless, only a year after Bernard Tschumi’s design was officially announced as the competition winner in October 2001,17 the Swiss-French architect clearly stressed the importance of natural light to his design for the New Acropolis Museum when he stated that the ‘central idea [underpinning the Museum’s design] is to allow Attic light to shine on the exhibits, as it did from the time of their creation.’18 Tschumi would also later emphasise that ‘the use of daylight is fundamental to this museum’,19 while he would further stress that, ‘Floating above these many challenges were the demands of the Attic light, at once serene and implacable, which had to be incorporated both as a defining element and an architectural material’, going so far as to state that, alongside marble, concrete and glass, ‘Light became a fourth material as well as a design requirement.’20

Imperial Acquisitions

The ‘unique Attic light’, when contrasted with the frequently overcast skies of London and the gloomy conditions of the Elgin Marbles’ home in the British Museum, also subtly alludes to the sculptures as imperial trophies; ripped from their natural environment by the servants of perfidious Albion, the sculptures were transported overseas and displayed in the cloudy capital of Britannia’s empire. Attempts to label Elgin’s acquisition of the Marbles, as well as the British government’s subsequent purchase of the sculptures and the gifting of the artworks to the British Museum, as imperial ventures are, however, problematic. It has frequently been claimed that Elgin abused his ambassadorial position in Constantinople to apply political influence on the Ottoman authorities and so obtained the controversial firman that allowed his agents to secure many of the best preserved sculptures from the Parthenon and other temples on the Acropolis.21 Nonetheless, when negotiating the removal of the sculptures, the Scottish aristocrat was acting as a private individual rather than in any official capacity.22 While Britain of the early nineteenth century was clearly an imperial power with colonies scattered around the globe, Athens was never part of its empire. Greece had, indeed, been under Ottoman rule for almost three-and-ahalf centuries by the time Elgin removed the sculptures, and few people in the early nineteenth century (or, indeed, modern historians or lawyers) would question the legal right of the Sublime Porte to ownership of the buildings that crowned the summit of the Athenian Acropolis. Nonetheless, when the Greek Foreign Minister, George Papandreou, was interviewed by the House of Commons Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport in the summer of 2000, he would emphasis the imperial power of Britain compared to the servitude of Greece: ‘I am not here to rake over the events of the past 200 years’, before pointedly noting that, at the time Elgin removed the sculptures from Athens, ‘Britain was then a vast empire, we were then subjected.’23 In emphasising that a foreign empire controlled Greece at the start of the nineteenth century and had dominion over many of the monumental treasures of antiquity that survived in the Greek landscape, Papandreou was underscoring the subject status of the Greek people at the time Elgin removed the Marbles, and, in so doing, was following the lead of Melina Mercouri who, at Mexico City in 1982, had noted: ‘Greece, as you know, was under Ottoman domination for four centuries. We began our national liberation movement in 1821. … But it was 18 years too late to save the marbles.’24

Over the course of the last decade, attempts have been made by Neil MacGregor, Director of the British Museum, to redefine his institution as a museum of the Enlightenment rather than the product of empire: a ‘Universal Museum’ with an encyclopedic collection offering visitors the ability to compare and contrast the sculptures removed from the Parthenon with artworks created by other great civilisations from around the world. The concept of the Universal Museum has, however, proved to be contentious; museologists such as Mark O’Neill have dismissed the idea as flawed and ‘deployed chiefly as a defense against repatriation claims.’25 The President of the New Acropolis Museum has also rejected the idea, referring instead to the imperial acquisitions that form a substantial part of the British Museum’s collection, as well as the postcolonial mindset that arguably lies behind the concept of the Universal Museum: ‘It’s not really a modern idea, it’s more an idea of the 19th century, a translation of the imperialism of the 19th century to the globalization of the 20th century.’26 However, Greek attempts to reclaim the Elgin Marbles by tarring the British Museum with the imperialist brush are themselves hamstrung by the fact that the Parthenon is itself a product of imperialism. The temple was partially raised from revenue derived from an annual tax paid by the increasingly reluctant allies of Athens who formed the Delian League – the collection of maritime states established in the wake of the Persian invasion of Greece in 480/79 BC. From 454 BC, the temple of Athena Parthenos also served as the repository of the wealth accumulated from the League. St Clair has therefore noted: ‘From the moment it was conceived in the fifth century BC, the Periclean Parthenon was a monument to imperialism. … [I]t asserted the identity of the people of Athens not only against non-Hellenes, but against other Hellenic city states such as Sparta, Corinth, or Argos. But, since the cost of building was, to a large extent, financed by monetary contributions forcibly levied from the numerous other Hellenic cities under Athenian domination, the grandeur of the building emphasised that imperial meaning more obvious than either the temples of other Hellenic cities or the predecessor buildings in Athens.’27

The Museum and the Marbles

It is clear that one of the Greek government’s primary objectives behind the design and construction of the New Acropolis Museum was to facilitate the repatriation of the Marbles on display in London. The 1989 architectural competition had made plain this aim and expectation when it was noted: ‘the envisaged return of the Parthenon pediment marbles (the so-called “Elgin Marbles”) necessitates the creation of corresponding areas for their display.’ The design programme would go on to add: ‘Since the repatriation of the original Parthenon sculptures is envisaged, room must be provided to facilitate their display together with the remaining architectural members and sculptures which are found in Greece.’28 Although no similar programme was ever made public for the architectural competition of 2000, nonetheless, Tschumi certainly had little doubt that the Museum was intended ‘to convince the world that the Elgin Marbles should come back.’29 The architect would thus write of the difficulties he faced when attempting to ‘design a structure whose unstated mandate is to facilitate the reunification of the Parthenon Frieze.’30 Greek politicians were also well aware that one of the primary objectives in building the New Acropolis Museum was to bring about a return of the Marbles from the British Museum, and in May 2005 the Greek Prime Minister, Kostas Karamanlis, issued a directive through the Culture Ministry in which he urged: ‘Works on the monuments, and on the new Acropolis Museum must be speeded up so that our country can present credible arguments both in seeking extra [European Union] funds for culture and in demanding the return of the Parthenon sculptures.’31

With the ‘unique Attic light’ a key argument in Greek governmental demands for the return of those Marbles removed from Athens by Lord Elgin, it was a principal requirement that the Parthenon Gallery – located on the top floor of the New Acropolis Museum, within which all the original sculptures from the Parthenon still in Greek hands, would be displayed alongside casts of those Marbles currently in London and other foreign museums (Fig 3) – be allowed access to vast amounts of natural light. On all sides of the Parthenon Gallery windows therefore reach from the ceiling to the seating shelf positioned approximately 50 centimetres off the floor. Great lengths, and indeed great expense, were thus taken to procure the most appropriate glass for the windows of the Museum to allow natural light to stream into the Parthenon Gallery, as Joel Rutten, an architect with Tschumi’s architectural company, made clear:

‘Because we wish to use glass that is as clear as possible and because Tschumi insists against undesirable green tints or strong reflections, we begin to research low-iron glass as well as silkscreen-dot technologies that filter light without adding colors or other unwanted effects.

The Parthenon Gallery is challenging because we want to maintain the maximum transparency in order to provide natural light for the sculptures and a direct view to the Acropolis as well as Athens’ hill, mountains, and the distant port city of Piraeus. Standing on the gallery should feel almost like standing at the top of the Acropolis. Professor Pandermalis shares our concern that the sculptures and the Frieze be seen in the same orientation and unique Attic light as originally intended. …

The eventual solution consists of a double-glazed layer that is silkscreened with a gradient of black dots so as to control heat gain and glare…

The next challenge involves keeping the glass façade as discreet and uncluttered as possible, using metal fixings so as to avoid cast shadows and interruptions in the views to the Parthenon.’32

The north-east corner of the Parthenon Gallery in the New Acropolis Museum. The sculptures from the east pediment of the temple are to the left, while the metopes are displayed on tubular steel supports, with the frieze visible behind. Such a presentation partially replicates the original arrangement of the marbles on the Parthenon, although the sculptures of the pediment are positioned below, rather than above, the other two sets of marbles. Photograph: Nikos Danielidis. © Acropolis Museum.

The desire to allow vast amounts of natural light to flood the New Acropolis Museum was certainly fulfilled in the completed building. The Parthenon Gallery in particular has frequently been described in such terms as ‘the sun-drenched top floor’,33 while the essayist Christopher Hitchens also drew attention to the illumination of the Parthenon Gallery, describing it as an ‘impressive space, drenched in Greek light.’34 The President of the New Acropolis Museum, Dimitrios Pandermalis, has also been eager to draw attention to the importance of the natural light that streams into the galleries, enthusiastically noting that ‘this is the Museum’s most thrilling asset: The light. So much so, that I’ve been thinking of having it managed, of having someone keep track of the light all day long! What I mean is that I’ve been thinking of putting a staff member in charge of the light.’35

Opinions of the New Acropolis Museum

The architectural community lavished praise on the interior of the New Acropolis Museum and transmitted their generally positive opinions to the wider public. Michael Kimmelman, writing in the New York Times, therefore noted that the New Acropolis Museum was ‘airy and light-filled inside, a home-inwaiting for the marbles.’36 Similar sentiments were expressed in The Economist in which it was noted that ‘both Greek and foreign visitors seem delighted by the museum’s spacious, daylight-filled interior.’37 The architect Suzanne Stephens also pointed out that ‘the interior of the museum provides a stunning setting for the Parthenon marbles displayed on its top floor. ... Indeed, the elegant design of many of the museum interiors, and especially the Parthenon Gallery, makes a convincing case for the Elgin Marbles … to be returned by the British Museum to Greece, and joined with the surviving originals.’ She went on to note: ‘The Parthenon Gallery’s space and majesty alone makes the strongest argument for returning the Parthenon marbles to their proper setting.’38 A year after opening, the Museum was even presented with an ‘Award of Excellence and Sustainability’ by the International Association of Lighting Designers.39

The overwhelming desire that natural light be allowed to play a major role in the New Acropolis Museum and aid the Greek government’s case for the return of the Parthenon Marbles did, however, place severe restrictions on the nature of the design and construction of the Museum. This was made clear by Arup, the consultancy firm that provided structural and mechanical studies during the design and construction phase of the Museum project: ‘More than any other quality, light is the theme of the New Acropolis Museum and a central requirement of the architectural design. Large glass surfaces on the facades and roof optimise the opportunities for natural light.’40 As such, the requirement that light be allowed to flood the galleries dictated the New Acropolis Museum take the form of a large, glass-fronted building positioned uncomfortably in the midst of the predominantly residential Makriyianni neighbourhood of central Athens (Fig 2). Nonetheless, a great many professional architects have written with approval of the external appearance of the new Museum. Nicolai Ouroussoff claimed the new museum to be a ‘building that is both an enlightening meditation on the Parthenon and a mesmerizing work in its own right. I can’t remember seeing a design that is so eloquent about another work of architecture.’41 Writing in Building, Dan Stewart also praised the new Museum, voicing the hope that ‘the beauty and restraint of the completed building will silence some of Tschumi’s critics.’42 In 2011 the New Acropolis Museum was the recipient of American Institute of Architects Honor Awards.43

There were, however, many critics left unimpressed with the gleaming glass exterior of the Museum. Despite her appreciation of the building’s interior, Suzanne Stephens would nonetheless note: ‘The dour mien of the New Acropolis Museum, with its sharp angles, black-fritted glass … and less-than-perfect concrete work evokes High Modernist commercial American buildings of the 1970s.’ She would go on to write, ‘from the outside it still looks like the box the Parthenon came in.’44 Likewise, Michael Kimmelman also expressed doubts about the exterior of the Museum noting that it was ‘forbidding and frankly ugly outside’, and commenting: ‘From certain angles it has all the charm and discretion of the Port Authority terminal in Manhattan.’45 One Greek architect and conservationist employed by the Ministry of Culture and thus speaking under condition of anonymity, referred to what he labeled as ‘the horror of the museum’, which he went on to describe in less-than glowing terms: ‘From the outside it looks like a factory. It’s almost a non building.’46 Many Athenians also expressed concerns regarding the ‘massive and barbaric’ structure,47 with one local resident voicing the complaint: ‘It’s like a huge spaceship has landed on top of one of Athens’s oldest neighborhoods.’48 Most scathing was Simon Jenkins’s assessment of the Museum that he described in The Guardian newspaper as ‘big and brutal, like something flown in overnight from Chicago.’ He would go on to compare the building to ‘the police headquarters of a banana republic.’49

The political, as well as architectural and curatorial, demands that vast amounts of natural light be allowed to pour into the galleries of the Museum did, however, contribute to the expense of the project and construction of the building would eventually cost €129 million. This was well above the figure of £29 (approximately €34) million the former British parliamentarian Eddie O’Hara – a leading Marbles campaigner and currently the Chairman of the ‘British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles’ – assured his fellow MPs was the price at which the Tschumi designed New Acropolis Museum had been commissioned by the Greek Government.50 Fortunately for the government in Athens, they were later able to convince the European taxpayer to pick up most of the bill for the Museum, and, as Prime Minister Karamanlis had hoped in 2005, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) contributed two-thirds of the overall construction costs.51

In the Shadow of the Parthenon

Natural light has also been employed to partially justify the decision to build the New Acropolis Museum just 300 metres from the Acropolis and repatriation campaigners have sought to bind the Acropolis to the new Museum through appeals to light and shade. Thus, in September 2012, another British parliamentarian, Andrew George – Chairman of the campaign group ‘Marbles Reunited’ – tabled a Private Members Bill at Westminster in which he urged his fellow MPs to press for action ‘to reunite these British-held Parthenon sculptures with those now displayed in the purpose-built Acropolis Museum in the shadow of the monument to which they belong, the Parthenon in Athens.’52 In December 2014, the human rights lawyer Geoffrey Robertson, currently providing legal advice to the Greek government to support their claim that the Elgin Marbles be returned to Athens, would also ask: ‘why should all surviving pieces of the greatest art in world history not be seen, reunited at the Acropolis Museum under a blue attic sky and in the shadow of the Parthenon?’53 Such assertions by non-Greek politicians and lawyers indicate the international nature of the debate surrounding the ownership of the Elgin Marbles. They also further emphasise the environmentally deterministic nature of the claim that, although no longer on the Acropolis, the sculptures on display in the New Acropolis Museum nevertheless remain linked to their original context through close proximity to the hill-top as well as the ‘unique Attic light’, with shadows cast by the Parthenon able to reach out and touch the Museum.

The claim made by both George and Robertson that the New Acropolis Museum stands ‘in the shadow of the Parthenon’, although deploying a common turn-of-phrase is, however, lacking in factual accuracy.54 The Acropolis is, after all, located to the north-west of the New Acropolis Museum; this results in shadows from the rocky hill-top being cast generally northwards and thus away from the Museum, in the opposite direction to that claimed by the MP and lawyer. Even in the late afternoon, when lengthening shadows cast from the Acropolis fall to the east, they never touch the Museum. Given the low elevation of the Museum relative to the hill, there is never any possibility that shadows cast from the Museum will touch the Acropolis, let alone reach all the way to the Parthenon on its summit. (See the afternoon shadows cast to the north-east of the Museum in Fig 2.) This might seem a pedantic point, yet both Andrew George and Geoffrey Robertson have visited the New Acropolis Museum and should know the topographical reality of the situation. Instead there is the rather disturbing impression that factual accuracy has been overridden in an effort to bolster emotive arguments in support of the repatriation of the Marbles.

Simple ignorance, an ill-judged turn-of-phrase, or ‘architectural licence’ might justify the unreliable information offered by some repatriation campaigners who, like George or Robertson, have referenced the manner in which the new Museum is linked to the Acropolis by the casting of shadows from the hilltop site.55 However, it becomes of greater concern when such statements are used by politicians like Andrew George to mislead the democratic representatives of the British people; MPs who have it within their power to force changes in museum legislation, or apply considerable political pressure on the Trustees of the British Museum, in an effort to repatriate the Elgin Marbles to Greece. (Though it is doubtful if many of the 650 MPs at Westminster – only 15 of whom supported Andrew George’s 2012 motion – were ever aware of the impossibility of shadows from the Parthenon reaching out to the New Acropolis Museum as George claimed in his bill.) Campaigners working for the return of the Marbles held in the British Museum already have many strong points in their favour; dubious or downright inaccurate statements presented to MPs at Westminster, the rest of the British people, and indeed the wider international community, might well backfire and instead call into question the integrity of some campaigners seeking to return the Marbles on display in the British Museum to Athens.

The Marbles in London

As the Greek government was upping the ante for the return of the Marbles from the British Museum as part of the ultimately doomed attempt to have the New Acropolis Museum finished in time for the 28th Olympiad, staged in Athens in 2004, Greek culture officials harked back to the words of men like Byron and Hardy, and were keen to stress the vast differences in light conditions that existed between London and Athens. In an interview in 2002, Elena Korka, head of the department for the Evaluation and Protection of Cultural Artifacts, part of the Greek Culture Ministry, therefore emphasised the difference between the natural illumination available in the Greek capital, especially when compared to that of the British Museum: ‘We’re not talking about a painting like the Mona Lisa that can be hung on any wall.’ Korka would go on to stress: ‘These marbles were sculpted for the Parthenon, designed to be on the Acropolis, under the natural light of the Attica sky, not a dimly lit gallery off Tottenham Court Road.’56 Similar sentiments have been expressed by the architect and repatriation campaigner Matthew Taylor, who has claimed that the presentation of the Marbles in the British Museum is seriously compromised by the nature of their display and the quality of the illumination in the Duveen Gallery; a room in which ‘the frosted glass roof lights ensure that everything is illuminated in an equal level of grey, with imperceptible shadows.’57

The assertion that the frieze and other sculptures of the Parthenon could only truly be appreciated in the light of the Greek capital, would also be voiced by Bernard Tschumi who clearly stated that the light in Athens ‘differs from light in London, Berlin or New York.’58 The President of the New Acropolis Museum was also keen to point out the importance on the need for natural Attic light in the galleries of his museum, while also providing what might be interpreted as a subtle poke at those institutions – most notable of which is the British Museum – failing to offer a similar quality: ‘The natural light that streams in, the same Athenian light widely praised by many of antiquity’s poets, and the great transparency that the museum has thanks to its many glass galleries in which the Parthenon is reflected prevent this museum from being a sterile space.’59 As recently as the summer of 2014, Christoforos Argyropoulos, the President of both the Melina Mercouri Foundation and the Consulting Committee of the Greek Ministry of Culture for the Parthenon Marbles, would claim that the Marbles removed by Elgin had to be brought back to the natural light of Athens rather than remain on display in the British Museum, a location he claimed was ‘an insult to the eyes of the viewer.’60

Although many architects and restitutionists have been eager to emphasise the aesthetic qualities that the New Acropolis Museum would offer the Elgin Marbles were they returned to Athens and placed on display in the light-filled Parthenon Gallery, there has been a failure to properly account for the context in which the Marbles were observed when affixed to the walls of the Parthenon. When originally displayed on the temple, the sculptures of the pediments, together with the metopes running around the outer walls of the Parthenon, were certainly open to direct sunlight and were bathed in bright Attic light. For these Marbles, the light and airy Parthenon Gallery of the New Acropolis Museum can therefore truly offer a worthy and stunning location (that is, if the mesh window blinds that shade the windows of much of the Parthenon Gallery are left open. However, for the sculptures of the Parthenon’s frieze, the New Acropolis Museum utterly fails to recapture their original architectural context or the light conditions in which they were displayed throughout most of antiquity.

Displaying the Frieze

The frieze that originally decorated the top of the temple’s cella is the marble jewel in the Parthenon’s crown. It is the Marbles of the frieze that are displayed in the main chamber of the British Museum’s Duveen Gallery; by contrast, the statues from the pediments, together with the sculptures of the metopes, are presented in bays to either end of the main hall. The frieze also dominates the Elgin Collection: of the original length of 160 metres (524 feet) of Pentelic marble carved in low-relief that originally ran around the cella, 75 metres (247 feet) is today preserved in the British Museum.61 By contrast, there are only 15 of the original 92 metopes displayed in the British Museum and, like the 17 figures from the pediments that are also on display in London, most of these sculptures are extremely bruised and battered, the amputations and disfigurements a result of long centuries of human violence, the eroding influence of wind and rain, while the acidic atmosphere of modern Athens would also eat away at the Pentelic marble during the second half of the twentieth century.62

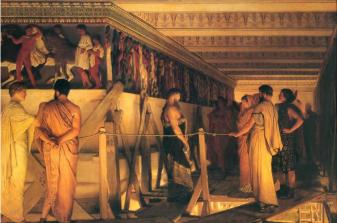

When the Parthenon frieze was originally installed on the temple it was never illuminated by bright sunlight. As such, the manner in which the sections of the frieze that survive in Athens, together with casts of those removed by Elgin, are ‘bathed in the Attic light’ that is allowed to stream into the ‘daylightfilled interior’ of the New Acropolis Museum, utterly destroys the context in which the frieze was originally displayed on the Parthenon. Running around the top of the exterior wall of the cella, the winding procession of figures carved into the frieze were instead destined to inhabit the shadows cast by the coffered ceiling directly above, while the outer colonnade of the temple also prevented direct sunlight from penetrating the gloom. This was recently emphasised by Panos Valavanis, a classical archaeologist at the University of Thessaloniki, who would correctly note that the frieze was ‘not entirely visible to the beholders, who from outside the temple could only see it through the spaces between the columns, the intercolumniations. As it was so high up and in a poorly lit space, the frieze could only be seen clearly at certain hours of the day, when, for example, the sunlight fell obliquely from the sides and enhanced the sculptural quality of the figures. The rest of the time it was illuminated by the light reflected from the surrounding white marbles.’63 Such knowledge is scarcely new. When, in 1868, the Anglo-Dutch artist, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, displayed his painting, Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, he was careful to emphasise the shadowy environment close to the ceiling of the cella, depicting the eponymous sculptor perched on scaffolding and boardwalks while presenting the frieze to some of the great and good of fifth century Athenian society (Fig 4). Unlike the sculptures that survive in both Athens and London, those presented by Alma-Tadema also show the Pentelic marble of the frieze brightly painted, allowing them to be more easily discernable amid the gloom of their surroundings.64

Oil on canvas painting by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends (1868). The Greek sculptor, Phidas, is depicted in the centre of the composition showing the frieze to Pericles and his mistress Aspasia. In the foreground to the left stand the philosopher Socrates and the young Alcibiades. Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

During the Late Roman imperial period, following a fire in which the Parthenon roof was destroyed by the blaze, the frieze did become far more exposed to the human gaze, as well as the eroding elements of wind and rain. (The fire was possibly the result of depredations carried out by the invading Heruli, a Germanic tribe who sacked Athens in AD 267.) A new roof was soon added but, rather than reach all the way to the outer colonnade, the replacement roof terminated at the cella. It has thus been noted by Dorothy King that ‘[t]he frieze, just below the old roof, was now exposed to the elements for the first time, on the windswept Acropolis’, while Professor Charalambos, President of the Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments, has emphasized that the removal of the roof and coffered ceiling of the peristyle would have the result of ‘utterly altering the lighting in which the Parthenon frieze was viewed.’65

The New Acropolis Museum does attempt to present some disparity in the manner in which daylight flooding through the large windows strikes the sculptures from the Parthenon: the pediment statues and the metopes are positioned further forwards – as was the case when they were on the temple itself – and thus closer to the windows and the direct sunlight. By contrast, the frieze is set further back, attached to the bare concrete wall that follows the dimensions of the Parthenon’s cella and usually remains protected from direct sunlight by the metope panels immediately in front (Fig 3). However, despite this attempt to recreate at least some of the variation in light conditions, because there is simply so much sunlight streaming through the Museum’s huge windows into the Parthenon Gallery, the effect does not come close to reproducing the darkling gloom that cloaked the frieze when it was on the temple during the Classical period – especially on overcast days when even less light would have been reflected off the walls of the cella or the columns to penetrate the shadows.

The manner in which the frieze is presented in the New Acropolis Museum thus utterly destroys the shadowy context of the original architectural setting of these sculptures. The light-filled Parthenon Gallery opens the frieze to dazzling daylight which, although a boon to visitors eager to inspect the details of the carvings, was certainly not the illumination envisaged by the architects and sculptors of the fifth century BC who purposely positioned the frieze in perpetual twilight. While the men, women and animals carved into the Pentelic marble of the frieze were intended to forever wend their ceremonial way through deep shadows, they now stand blinking in the bright natural light of the New Acropolis Museum. Slit skylights positioned above the internal concrete walls into which is set the frieze allow even more natural light to fall on these sculptures from directly above, completely unlike the environment in which the frieze was displayed throughout most of antiquity (Fig 5). When originally adorning the Parthenon, the frieze was located directly below the coffered ceiling of the peristyle which also deepened the shadows at the top of the cella in a manner completely at variance with the high ceiling in the Parthenon Gallery (compare the relatively cramped and dark space depicted in Alma-Tadema’s painting against the well-lit and airy display of the frieze in the New Acropolis Museum, Figs 4 & 5). It is, therefore, no surprise that although Professor Valavanis accurately described the location of the frieze as it was originally displayed on the fifth century BC Parthenon as ‘a poorly lit space’ that was ‘not entirely visible to the beholders’, the Greek academic would, by contrast, describe in a positive manner the way in the frieze displayed in the New Acropolis Museum is ‘bathed in the Attic light that shines through the windows of the museum.’66

The frieze as displayed in the Parthenon Gallery of the New Acropolis Museum. Illuminated by natural light provided by the main windows and slit skylights above, the honey-coloured original marbles contrast sharply with the white plaster casts from those sculptures currently in the British Museum. Photograph: J. Beresford. Reproduced with the permission of the Acropolis Museum.

The natural illumination provided by the ‘sun-drenched top floor’67 of the New Acropolis Museum thus destroys the original light conditions in which the frieze was originally presented when on the ancient temple. Furthermore, the Parthenon Gallery also supplies additional illumination for these sculptures through means of overhead electrical spotlighting.68 Provision of skylights and artificial lighting with which to better illuminate the frieze is no bad thing, and certainly provides visitors to the museum with a far more detailed view of the sculptural detail of the frieze than would ever have been possible for the ancient Athenians. However, they seriously undermine the claim that the New Acropolis Museum closely replicates the light conditions that the frieze experienced when originally attached to the Parthenon. The original architectural context of the frieze, and the intensity of the illumination with which the sculptures would have been visible to fifth century BC Athenians, has thus been firmly denied by Bernard Tschumi’s light-box museum.

Positioning the surviving metope panels between narrow steel columns that run around the entire Parthenon Gallery, allowing the metopes to be displayed at a slightly greater height relative to the panels of the frieze (Fig 3), also allows considerably more natural light to illuminate the frieze than was the case when the sculptures were set on the Parthenon during antiquity. Moreover, because so many metope panels have been lost over the course of the last 2,500 years, there are large spaces between the metal columns that have been left empty in the Parthenon Gallery, especially in the central portions of both the northern and southern flanks,69 allowing natural light to flood through these gaps and provide additional brightness to the frieze behind. Thus, in the central portion of the northern side of the Parthenon Gallery, there are 18 metope panels completely missing (panels VI–XXII, XXVI) (Figs 3, 5). On the southern side of the gallery, five central panels are completely lost or destroyed (XXIV, XXV, XVIII, XXIII, XXV), while an additional eight (XXII, XXVI, XXVII, XIX–XXII, XXIV) are so badly fragmented that they have been set in transparent Perspex, a material that also allows daylight easy access to illuminate the frieze. The Parthenon frieze in the New Acropolis Museum is therefore presented in a light environment utterly different to that in which it was displayed when set on the temple during the Classical era.70

Mesh Blinds and the Metopes

The bright Attic light that is frequently regarded by campaigners seeking the repatriation of the Elgin Marbles to Athens as a crucial component in the display of the sculptures in the New Acropolis Museum is also, rather surprisingly, frequently denied access to much of the Parthenon Gallery. Black mesh shades are invariably pulled all the way down to the seating bench along the entire length of the south-facing side of the gallery (and often on the eastern and western sides as well). Only along the northern facing windows of the gallery – the side that offers views directly towards the Acropolis – are the blinds left open. Such a measure protects visitors from the glare and heat of the sun, especially during mid-summer. However, the blinds are also usually drawn closed along the southern side of the Parthenon Gallery even in wet and cloudy conditions, preventing natural light from entering the room from this direction (Fig 6). It has, therefore, been noted by Dimitris Plantzos that the ‘drapes and blinds are sensibly placed on the glass walls [of the New Acropolis Museum], as an afterthought perhaps, in order to obscure the view to the surrounding polykatoikies [apartment buildings], commanding our gaze north, towards the newly restored Parthenon.’71 The use of the blinds running along the glass walls of the Parthenon Gallery as a means of focusing the attention of visitors on the archaeologically scenic northern vista, while presenting a mesh barrier that restricts visibility over the modern concrete apartment blocks which dominate views to the south, east and west, is thus regarded by Yannis Hamilakis as deliberate curatorial practice at the New Acropolis Museum:

The casts of the pediment statues from the southern end of the east side of the Parthenon, with the original Pentelic marble metopes behind. Note that, despite the overcast skies of early December, there are blinds on the windows. The sculptures are clearly denied unimpeded access to the natural daylight; contrast the brightness of the single narrow ray of daylight penetrating through a gap in the blinds and across the floor of the Parthenon Gallery compared to the more muted light that has to pass through the black mesh of the blinds. The Marbles on display along the southern side of the New Acropolis Museum (facing out over the modern cityscape rather than towards the ancient monuments on the Acropolis) are instead viewed in considerably more shaded conditions than would be the case were they in their original positions on the exterior of the Parthenon. Photograph: J. Beresford. Reproduced with the permission of the Acropolis Museum.

‘The management of the gaze is the primary concern of its archaeological and museographic apparatus. Glass architecture enables visual contact with the monument [i.e. the Parthenon] and lets light in, but it can have another advantage: it makes the control of viewsheds from the vantage point of the museum possible, and the vistas experienced by the visitors, changeable (hence the drapes and blinds Plantzos refers to, which hide ‘ugly’ modern blocks, and direct the gaze towards the Acropolis).’72

Regardless of whether the blinds on the south, and sometimes the east and west, sides of the Parthenon Gallery are drawn closed because of the desire to protect visitors from the brightness and heat of direct sunlight, or rather to obscure the Athenian cityscape from view, the use of these mesh screens clearly undermines the oft-made claim that the sculptures on display in the New Acropolis Museum are lit by the same natural light as illuminates the temple from whence they came. It has thus been noted that when the sculptures were located on the Parthenon: ‘The metopes and the large sculptures on the East and West pediments were exposed to direct sunlight, which would change dramatically throughout the day. Deep reliefs both in the frieze and metopes gave rise to marked shadows.’73 In the New Acropolis Museum, however, use of the blinds creates a more shaded environment that completely changes the nature of the light passing into the room and illuminating the display of the metopes as well as the statues of the pediments. Indeed, all the 15 metopes that were removed from the Acropolis by Elgin and which are presently displayed in the British Museum originally came from the south-facing flank of the Parthenon. If these metopes were installed in the New Acropolis Museum then they would have no view of the Parthenon and instead face out over the concrete rooftops of twentieth-century urban architecture. The blinds that are invariably drawn closed along this entire side of the gallery would also prevent the natural Attic light from reaching these south-facing Marbles unhindered. Use of the window blinds in the Parthenon Gallery thus makes a mockery of the claim that natural light is one of the most important features of the New Acropolis Museum. Regular use of the blinds on those windows that face away from the Acropolis also calls into question the effort and expense lavished on the Museum’s windows: why comply with the architect’s demands that glass of ultra transparency be procured for the building so that natural light might be allowed to flood the exhibition spaces when the staff of the Museum make persistent use of the blinds and so restrict that same light from entering the galleries?

Athens or London?

Given the light conditions in the Parthenon Gallery, Tschumi’s stated ‘desire to replicate, as far as possible, the outdoor conditions under which the Parthenon Frieze and the Acropolis sculptures were originally seen’,74 must be considered a failure. Nonetheless, in the years leading up to, as well as following, the inauguration of the New Acropolis Museum, Tschumi’s claims have gone unquestioned, and, as has already been seen, a great many architects, archaeologists, as well as campaigners seeking the return of the Elgin Marbles, have followed the lead of Greek politicians in eulogizing the qualities of the sunlight of the Greek capital and the manner in which the New Acropolis Museum has effectively harnessed natural Attic light to mimic the original architectural context in which the frieze and other sculptures were viewed by ancient Greeks.75 However, given the disparity that exists between the heavily shadowed location at the top of the Parthenon’s cella in which the frieze was originally displayed, compared to the brightly lit gallery in which it is now on show in the New Acropolis Museum, together with the enthusiastic use of window blinds to focus the gaze of visitors away from the modern cityscape and diffuse the harsh sunlight illuminating the metopes and pediment statues, then such claims are, at best, clearly overstated; at worst they appear wildly inaccurate and highly misleading.

It is, in fact, arguably the Duveen Gallery of the British Museum that comes closer to capturing the shadowy environment of the Parthenon that was originally home to the frieze. As has already been seen, the Parthenon Gallery is frequently described as located on ‘the sun-drenched top floor’ of the New Acropolis Museum, with the sculptures ‘bathed in the Attic light’; conversely, Greek culture officials have been eager to claim that the British Museum displays the Marbles in ‘a dimly lit gallery’, while restitution campaigners also describe the Duveen Gallery’s ‘imperceptible shadows’. If such opinions are to be taken at face value, then it would appear that the more shaded environment of the British Museum offers the frieze a closer match to its original gloomy location on the Parthenon of the fifth century BC. If the curators of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum could be persuaded to dim the lights of the gallery on particularly overcast days or at the onset of nightfall, then visitors might be rewarded with a view of the frieze similar to that witnessed by visitors to the Parthenon during the Classical era (though obviously minus the paint, and with the frieze conveniently presented close to eye-level).

None of this is to claim that the Marbles currently in London should remain in the British Museum primarily because the Duveen Gallery admits less natural light than is currently the case in the New Acropolis Museum and therefore offers a more accurate approximation of the conditions in which the frieze would have been displayed when first affixed to the Parthenon. Indeed, there can be little argument the Parthenon Gallery offers a truly wonderful setting in which visitors to the New Acropolis Museum can inspect and appreciate the sculptures on display. It is beyond argument that the layout of the Parthenon Gallery allows visitors a far clearer understanding of how the frieze, metopes and pediment sculptures were all positioned relative to one another when on the monument than is the case at the British Museum. Neil James thus described the top floor of the New Acropolis Museum as ‘a gallery that sets out the temple’s sculpted pediments, metopes and friezes according to the original plan. They are hung on a framework that matches the Parthenon’s colonnades at the same orientation and scale and on the same plan as the great temple itself … so that, walking along the gallery, we can imagine ourselves in the temple by just looking out at it on the Acropolis.’76 By contrast, the sculptures displayed in the British Museum are considerably more difficult to relate to the original temple, with Mary Beard noting that the manner in which the presentation of the frieze and rest of the Elgin Marbles as displayed in the Duveen Gallery is difficult for most visitors to relate to their original positions on the Parthenon because they are displayed ‘inside out.’77 Were the Marbles from the Elgin Collection ever to make their reappearance in Athens, the New Acropolis Museum would undoubtedly be a superb location in which to reunite them with the rest of the surviving sculptures. What should be emphasised, however, is that restitutionists who claim that the frieze should be returned to the Greek capital so that it might once again bask in the natural light of Athens, and be viewed in the light environment for which it was originally created, are presenting an erroneous argument. Claims such as those made by Yannis Aesopos, Professor of Architecture at the University of Patras, that the frieze and other sculptures displayed in the Parthenon Gallery of the New Acropolis Museum ‘are lit by the same natural light and receive the same shadow in an installation that approximates its antique predecessor’,78 simply do not stand up to architectural scrutiny.

Conclusion

The natural light of Athens has long been regarded as an important factor in appreciating the Parthenon and the sculptures that originally adorned the exterior of the fifth century BC temple. The glass and concrete architectural design of Bernard Tschumi’s New Acropolis Museum deliberately references this distinctive light. Allowing natural light to stream into the building was considered an architectural necessity, not so much for viewing pleasure, nor yet to allow visitors to achieve a better architectural understanding of the Classical temple and its marble decoration, but as a powerful weapon to the wielded in the campaign to reclaim the sculptures removed by Lord Elgin and now on display in the British Museum. This paper has attempted to explore the claims made by the architects of the New Acropolis Museum, as well as many Greek politicians and heritage professionals, regarding the need for natural light to play a leading role in the architecture of the Museum, and the considerable emphasis that has been placed on the building as the only suitable venue for the display of the surviving sculptures that once adorned the Parthenon. Although the manner in which the New Acropolis Museum allows natural light to stream into the galleries, especially that of the Parthenon Gallery, is frequently offered as a key argument in favour of repatriating the Elgin Marbles to Athens, nonetheless, the best preserved of the sculptures – the Marbles that comprise the frieze – are poorly served by the illumination within the Museum. Rather than strengthening the argument for the return of the Elgin Marbles through reference to natural light mimicking the conditions in which these sculptures were originally displayed on the temple, the overprovision of light in the presentation of the frieze in the New Acropolis Museum has instead undermined the environmentally deterministic position held by many campaigners seeking the repatriation of the Marbles through appeals to the ‘unique Attic light’. The use of window blinds along the southern side of the Parthenon Gallery which prevents daylight from illuminating the metopes facing in this direction is also highly problematic for those who have referenced the light as an argument in favour of restitution. Rather than a genuine attempt to offer visitors to the Museum a faithful appreciation of the architectural context in which many of the sculptures were displayed when originally placed on the Parthenon in the fifth century BC, the design of the New Acropolis Museum’s Parthenon Gallery primarily appears to have been Tschumi’s response to demands made by Greek politicians intent on bolstering their claim to the Elgin Marbles through emotive appeals to the light of Athens.