A New Era of Design

The ever-growing awareness of global warming’s impact on the inhabitability of our planet is continuously strengthening the view that sustainability should become the core concept for a theory and practice of design in the twenty-first century. Given the significant role played by the building industry in the erosion of our common ecosystem, it is difficult to overstate the importance of the green agenda for the future of the architectural discipline. It is widely known that the core objective of sustainable architecture is to stimulate a design revolution founded on the construction of a socio-ethical platform regarding the ecosystem. Catherine Slessor argues that “sustainability should not be seen simply as a corrective force, but as a new mandate for architecture,”1 Paul Hyett asks, “If sustainable design isn’t a moral imperative, what is?”2 and Brian Edwards goes further, claiming that “no architecture has moral validity unless it addresses (. . .) being environmental sustainable.”3 However, despite fostering a strong sense of environmental responsibility, when we look at green architecture we see designs fixated in measuring and assessing energy consumption patterns, greenhouse gas emissions, material usage and waste management. So how exactly should architecture pursue building “in harmony with the environment,” the slogan endlessly repeated in “green” literature? In fact, what exactly are we referring to when we talk about sustainable design? Solar panels and green roofs?

One very tangible outcome in the advance of green architecture is the rise of a new range of architectural vocabulary: LEED, BREEAM, SmartCode International Energy Conservation, Code for sustainable homes, ASHRAE 90.1, energy standard, cradle to cradle, Factor 4, carbon credits, ecological footprint, eco-efficiency, biomimicry, biophilia, adaptive design, low-energy home, carbon-neutral building, passive solar house, energy-plus building, self-sufficient home . . . these novel concepts are indicative not only of the myriad of differing ideas, tactics and methods that are emerging from the domain of sustainable design but also of the emergence of competing environmental benchmarks. Green architecture has become undeniably dependent on the building’s “ecological rating”: the quantitative data produced by assessment models that certify the environmental friendliness of a building’s design, but recent inspections have revealed major failings in green standards.4 And given that each green benchmark is able to define its own criteria, it is not surprising to realize that to “prove” the sustainability of any architectural project it is sufficient to pick the most favorable assessment model and tweak some of the building’s features.5

Sustainability has become a heavily disputed field for architecture, and there is a growing suspicion that, as Sanford Kwinter puts it, “what is required to give birth to a true ecological ‘praxis’ for our cities and our civilization cannot be found or resolved within the scope of sustainability workshops, environmentalisms, policy reforms, and technologic and scientific research and their applications.”6 If the ends of sustainable architecture are posited in making design “part of the living habitat” and “in touch with nature,” the means of sustainable architecture are concentrated on establishing a meticulous quantitative assessment of the building’s consumption patterns. And the realization of this opposition between technocratic environmental standards and its deep message of immaterial and holistic nature-thinking seems to indicate that “sustainable architecture is the product of the simple juxtaposition of two concepts, without considering their mutual implications, and that by taking its agenda for granted we are defusing the agency of design.”7 In order to examine this deadlock, we are required to take a step back and turn our focus on the contemporary green architectural production to critically pinpoint what are the precise links between a building’s ecological principles, its design process and their respective outcomes.

Pinpointing Green

Technology

In a telling declaration presented at the 11th Venice Biennale in 2008 entitled “Revolutionizing Architecture,” Jeremy Rifkin, alongside Enrich Ruiz-Geli, Jose Luis Vallejo, Jan Jongert and Stefano Boeri, proposes a “radical transformation of the role of the architect”: “We are committed to a revolutionary new concept of architecture in which homes, offices, shopping malls, factories, and industrial and technology parks will be renovated or constructed to serve as both power plants and habitats.”8 This radical reconceptualization of the architectural object as a power plant, the “transforming the building stock of every continent into micro–power plants to collect renewable energies on site”9 is the second of the five pillars of Rifkin’s Third Industrial Revolution, a concept that explores how contemporary technologies can define a path toward restoring the planet’s ecological equilibrium.10 This is a vision shared with enthusiasm by many other progressive architects and urban planners, and understandably so because it seems to point to a renewal of the legitimization of the modern project in today’s architecture: It is sufficient to recall Reyner Banham’s Theory and Design in the First Machine Age and Martin Pawley’s Theory and Design in the Second Machine Age to point out that Rifkin’s Third Industrial Revolution establishes clear lines of continuity with the history of architecture of the twentieth century. But this seeming return to a universalist narrative of profound change and societal redemption should raise some suspicion.

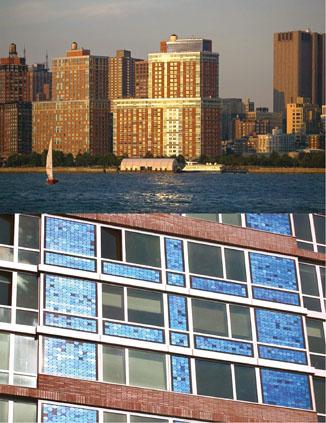

Let us take an example praised by a number of experts on green design: the award-winning Solaire in New York, the first high-rise certified by the U.S. Green Building Council.11 It is a 27-story housing building situated in New York City’s Battery Park, a prime location with a view over the Hudson River. It features rainwater reuse equipment and façade photovoltaic cells that reduce its energy consumption by 35% when compared to a similar size non-green building.12 However, the installation of green paraphernalia allowed private developers to receive public funding and to successfully negotiate with the council the halving of the otherwise mandatory 20% provision of affordable housing units. When it opened in 2003, monthly rents ranged from $2,500 to 9,000 and at the moment there is only one one-bedroom apartment available for a $5500 monthly rent,13 making the development accessible only to high-income earners. Here, the predicament is obvious: By surrendering social goals in favour of energy savings and carbon emissions, Solaire epitomizes the idea of “resortification” of sustainability: It is a luxury residential tower that exploits technology and legislative loopholes to instigate social segregation and gentrification, deepening the social rift in the urban realm.

Biomimetism

Another path toward sustainability lies in crossbreeding science with a deeper, broader, more holistic vision of the environment. This hypothesis can be typified by cradle to cradle, a philosophical concept and a life-cycle assessment product benchmark co-invented by the award-winning leading green architect, William Mcdonough. In Cradle to Cradle, the cherry tree is famously presented as a model for design: The cherry tree “enriches the ecosystem, sequestering carbon, producing oxygen, cleaning air and water, and creating and stabilizing soil. (. . .) it harbours a diverse array of flora and fauna, (. . .). And when the tree dies, it returns to the soil, releasing, as it decomposes, minerals that will fuel healthy new growth in the same place.”14 For McDonough, “Nature is a source of both sustenance and exquisite design (. . .). Form can become a celebration, not simply of human intelligence but of our kinship with all life.”15 Green guru David Orr praises McDonough’s approach to design as an example of what he calls “full spectrum design,” . . . “a strategy rooted in the ancient meaning of the word “religion,” which means ‘bind together.’”16 The word “religious” here is not to be taken lightly: what is really being envisioned here is nothing less than the foundation of a new physical and transcendental relationship between man and the environment. Earlier in the Hannover principles, McDonough states, “Respect relationships between spirit and matter. Consider all aspects of human settlement including community, dwelling, industry and trade in terms of existing and evolving connections between spiritual and material consciousness.”17 This use of nature as a poetic and functional metaphor can be appealing and inspirational; however, three questions seem to emerge: Firstly, is the idealization of a beautifully and perfectly structured nature a truthful representation of the non-human biologic and geologic collectives “out there”? Secondly, should sustainability be conflated with a matter of belief? Are not we dangerously close to the territory of magical thinking – the notion that if our symbols are good enough, then reality will follow? And, thirdly, how is this transcendental message compatible with the quantity-driven product benchmark certification that it aims to uphold?

The Solaire by Pelli Clarke Pelli, New York (2002). A fully air-conditioned LEED Platinum rated residential high-rise. A trade-off between socio-territorial equilibrium and energetic gains © Jeff Goldberg/ESTO.

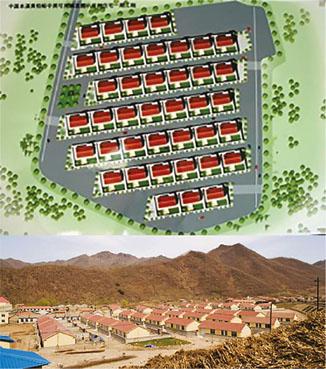

After an initial period of enthusiastic popularity, some of McDonough’s designs and the Cradle to Cradle benchmark itself has recently been under heavy criticism. To begin with, there seems to be an ingrained conflict of interests since McDonough is a hired architect or consultant for the companies whose products Cradle to Cradle is certifying. Additionally, McDonough does not disclose any of the certification data, not even to his clients, claiming it is part of his company’s intellectual property,18 which does not seem to be compatible with an enterprise that is trying to make a case for the inclusion of “nature” into the democratic arena of society: we usually find this kind of procedural “blackboxing” in the obscure world of corporate practices in an attempt to evade external scrutiny. But, as Latour argues, blackboxing is a condition embedded in technological processes – it relieves the user (and to an extent, also the designer) from the cognitive burden of having to understand all the internal or external relations of scientific and technical work. “When a machine runs efficiently, when a matter of fact is settled, one need focus only on its inputs and outputs and not on its internal complexity. Thus, paradoxically, the more science and technology succeed, the more opaque and obscure they become.”19 The problem here, of course, is the expansion of this “success by invisibility” condition of technology to Cradle-to-Cradle, which leads to a “technocratization” of design. Therefore, it is not exactly surprising that some of McDonough’s projects have been called into question because of their unexceptional environmental performance and design failure. Post-occupancy monitorization of some of their buildings detected severe discrepancies between the real energy sourcing and consumption and what the Cradle to Cradle certification stipulated. A recent energy consumption survey carried out in the Adam Joseph Lewis Center, a project regularly presented by McDonough to showcase the virtues of Cradle to Cradle, revealed that it consumed twice as much energy as the Cradle to Cradle certification specified, and that 84% of its power came from non-renewable power sources.20 But a more shocking example is the Huangbaiyu project. The objective of this project was to create a model for China’s first low-density self-sustaining rural community to be replicated throughout the Chinese countryside, in a very ambitious resettlement plan that would involve millions of people. However, the result of the project is not an auspicious one. Only phase one has been completed, and by 2006 only two families had moved in. The village consists of arrays of rationally ordered and centralized housing reminiscent of a typical Western suburbia. The detached houses include a garage when the farmers do not own nor can they afford a car, but provide no space for domestic husbandry. The project proposed to use locally sourced sustainable materials, but the houses ended up being built using coal-dust (which represents a health risk) and the total cost tripled. Despite being part of the concept, solar panels were not installed, and the biogas plant designed and built specifically to power the houses of this community was supposed to run on leftover corncobs and stalks, but this farm waste is the winter food supply for the cattle, so the biofuel has to be imported.21 Intending to “provide a higher quality of life for the villagers and to exemplify a more hopeful future for the children,”22 McDonough deliberately rejected the existing modes of inhabitation and production, imposing a radical reorganization of the household, the community and its economy. This astonishing example indicates the shortcomings of Cradle to Cradle’s authoritative design process. Its reliance on an idealized natural determinism supported by a self-righteous transcendentalism actively contributes to disconnect design practice from the socio-economic materiality of the site. Huangbaiyu exposes how treacherously seductive sustainability can be as a marketing tool.

Huangbaiyu Cradle-to-Cradle Eco-Village, China (2004): Site plan and bird’s eye view after the completion of the first phase. Disregarding existing communities, its infrastructures and modes of production, this bio-deterministic project produced a decontextualized piece of architecture, out of touch with the real “nature” of the site © Shannon May.

Aesthetics

Given the inadequacies of these two examples that address our ecological predicament by proposing a revolution by design, can we find a more effective path toward sustainable practices by proposing a revolution to design? Can a drastic transformation to the disciplinary domain of design stimulate an innovative and creative architectural production that both integrates and expresses the primacy of the environmental issues at hand? This is not exactly a novel proposal. In an early stage of the debate regarding sustainability, in 1996 the Solar Charter, a document sanctioned by a number of leading architects (such as Alberto Campo Baeza, Norman Foster, Nicholas Grimshaw, Herman Hertzberger, Frei Otto, Juhani Pallasmaa, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers), explicitly conveys the urgent need to devise a “new” architecture committed to emphasizing the visual appeal of green technologies: “New design concepts must be developed that will increase the awareness of the sun as a source of light and heat; for an acceptance of solar technology in construction by the general public can only be achieved by means of convincing visual ideas and examples.”23 Inaki Abalos expanded this idea, arguing that a new and specific aesthetic order should arise from the sustainability mantra: “From the point of view of contemporary architectural culture (. . .) a particular idea seems crucial in order to approach this confusing panorama which has been left unattended by universities, at least in its cultural implications: if there only exists an aesthetic debate, if there is an idea of beauty following sustainability, it will be here to stay. It is necessary, and urgent, to propose a debate (. . .) in search for minimum agreements, a consensual system for working on sustainability, to render it fruitful on a technical, critical and aesthetic level.”24 On a basic level, the fundamental question being asked here is what should sustainable architecture look like? Or, what new results could be produced by a new emphasis on the visual compositions of sustainable design?

A widely published project that explores these ideas is Stefano Boeri’s award-winning Bosco Verticale, a two-tower residential development whose generous balconies feature 900 trees and over 2,000 shrubs. Boeri claims that the project is a testimony for a “democratic environmental policy,” a non-anthropocentric urban ethic that “subtracts our species from its pedestal” – a genuine celebration of the architecture’s newfound role as a generator of microclimates and instigator of biodiversity: “We must think of accepting a relationship with nature on equal terms in cities, ensuring that it has its own autonomy and is not unendingly influenced by the needs of man. We must begin to foresee spaces for a nature that is close to us and yet is not controlled, toned down, or made artificial.”25 But we have to wonder if inserting trees on a high rise is not in itself a deeply artificial approach that contradicts its conceptual framework. Is this project a serious exploration into the emergent properties of a newly attained ecological consciousness, or is it an ostensive manipulation of “nature” in order to fabricate a fashionable piece of green iconography? Are not we sanctioning a territorial vision of landscape eco-tokenism? Despite its undeniable tectonic ingenuity, Bosco Verticale seems to end up reinforcing the rigidity of the disciplinary boundaries of the architectural practice it is trying to dissolve.

(a) Boeri’s Vertical Forest: Re-naturalized nature © Mauro Gambini. Image use granted under creative commons - Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) (b) A tree, pulled by a crane, about to be rooted in its new habitat above ground. © Fred Romero. Image use granted under creative commons - Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

Despite being far from composing a comprehensive depiction of the production of green architecture, these disparate examples show a compulsion to respond to the ecological crisis by envisioning nothing less than a complete transformation of the world through clear-cut strategies and universal solutions that lack the ability to grasp the reciprocal implications and inherent contradictions between architecture and sustainability. This seems to point out that at least part of the allure of green architecture lies in the way it echoes a time when architecture had a clear, ambitious and global agenda for social and cultural progress propelled by newly available technologies and legitimized by the goal of redefining society. If, on the one hand, the arguments presented so far have only been concerned with the symptoms of the problem, on the other, they seem to point out that its underlying causes can be situated in the (suppressed) desire to promote a return to the unfinished project of modernism and to use new design freedoms brought by ecological consciousness to articulate a perfectly idealized and disconnected notion of nature with contemporary patterns of human use and consumption. This proposition will be the focus of the next section.

Recomposing Green

Re-Modern

“Modernism has so intoxicated the very militants of ecology (. . .) that they have proposed to reuse nature-and-society, this time to ‘save nature’, promising us a future where we should be even ‘more natural’! Which means, if you have followed me, even less human, even less realistic, even more idealist, even more utopian. I am all for recycling, but if there is one thing not to recycle, it is the notion of ‘nature’!”26

In a recent documentary on Norman Foster, the architect is shown in a 1970s’ commercial presentation, explaining that a sandwich panel is a much superior material than concrete or brick because it offers the same thermal performance while being much lighter and light permeable: “This is a sandwich panel. Nice and light, weighs but a few ounces, not half a tonne. Lets the light through, very beautifully. Compare that with the concrete wall, half a tonne of brickwork … They are all the same performance.”27 The intense continuity between the modern, the high-tech and the green movement are not exactly breaking news; in fact, this connection has been explored by Catherine Slessor, who introduced the concept of Eco-tech: “Examples of this might include a structural system based on and engineered to resemble a giant organic ribcage or a translucent cladding panel that has a high level of insulation, or an environmental control system that can forecast the demands of building users and respond accordingly.”28 For Slessor, Eco-tech is a celebrated upgrade of high-tech architecture because it reinstates the building as a performative and communicative machine.29 However, there is an obvious dilemma: How can sustainability avoid becoming a green revival of the heroic but dogmatic modernism whose self-centred belief in science and technology fuelled dreams of urban progress and social redemption? For Richard Rogers, “the problem is not with technology, but with its application”: Perhaps we can say that when technology is used to secure the fundamentally modern principles of universal human rights – for shelter, food, healthcare, education and freedom – the modern age attains its full potential. It is here that the spirit of modernity finds its very expression.”30 It is interesting to note here that, for Rogers, sustainability is not only an extension but, more importantly, an inherent condition of modernity itself. But, in this context, what is the role left for nature? With the advent of sustainability, nature, the abstract green horizontal plane revealed by the building’s detachment from the ground, as if to further emphasize the modern split between man and nature, now has to be embedded in the design process. At Norman Foster’s Swiss Re, a much celebrated green project, the generation of architectural form is explicitly contingent to the digital processing of nature: sunlight exposure, wind patterns, energy flows, air movements are run through computational models to effectively shape design.31 Here, architecture becomes a digital literal metaphor of “nature.” But this is a process that contributes to the expansion of the apparatuses of control over the “natural” space, ironically furthering the “artificialization” of our environment.32 It is not so much that “nature” has been made part of the design process, but that design has found processes to absorb selective elements of nature-data, only to create the illusion that we are moving in the direction of overcoming the alleged divide between nature and society. “Monitoring, regulating, controlling flows: is ecological ethics and politics just this?”33 asks Tim Morton. Reflecting on his own work, Norman Foster writes: “Swiss Re builds upon the example we pioneered at the Commerzbank Headquarters in Frankfurt, which stemmed from a desire to reconcile work and nature within the compass of an office building.”34 At the Commerzbank, a rotating internal garden serves as an environmental device that evidently enriches the user’s spatial experience of the building. However, it is difficult not to think of the garden as another mechanism of environmental and corporative regulation of people and its surroundings that reinforces the idea of architecture as a creator of artificial boundaries.

But arguably the most emblematic example of sustainability on a large scale is Masdar City, a planned zero carbon city in Abu Dhabi, that embodies the fundamental paradox of sustainability: inside the city walls we are in a sustainable environment, but once we step outside, we are in unsustainable territory. Arguably, Masdar City could have been devised as a green extension of an existing settlement, but the appeal of generating a self-sufficient, autonomous, tabula rasa eco-utopia in the desert was too great to be ignored. Now that the development has halted and it has been declared that the partially built city will never reach its green goals, Masdar may soon become the world’s first sustainable ghost town.35

But how can we escape this deeply rooted modern trap that compulsively projects sustainability as a self-contained and perfectly delimited eco-enclave self-legitimized by the promise of a harmonious relationship with nature? According to Timothy Morton and Bruno Latour, it is precisely sustainability’s idealistic fantasy of environmental redemption that prevents us from envisioning nothing less than a radical disruption of the way our habitats are designed 36 ,37 . The whole notion of sustainability and ecological design is predicated on the idea that no human action can occur without an environment. This means that there is no outside space where the unwanted consequences of our collective actions could be sent to disappear: “Architecture that depends on air conditioning is predicated on the notion of “away.” But there is no “away” after the end of the world. It would make more sense to design in a dark ecological way, admitting our coexistence with toxic substances we have created and exploited.”38 Saying that architecture is against nature makes the same sense as saying that a prosthetic leg in a dismembered person is against nature, so maybe, the first step towards the constitution of sustainable design would be to oppose this romanticized and static notion of nature and, as a consequence, to dissolve the idea that architecture is obliged to protect “nature” or save the environment. This does not entail a decrease in the role of architecture, on the contrary. An architecture liberated from the shackles of nature may reveal its outcomes beyond the programmed functions and intended consequences, and therefore allow the construction of new pathways to ecological designs. But, still, how should architecture address issues regarding individual and collective behavior and the negative impact of their consumption patterns on the ecosystem?

Consumption

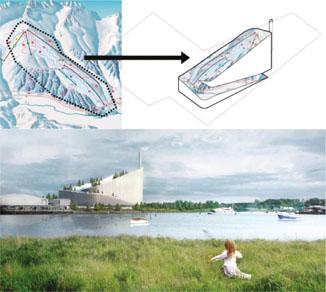

It is a well-known fact that sustainability is a growing market. As consumers become more eco-conscious,39 companies will go to ever greater lengths to present themselves as environmentally friendly. But can a real ecological impact be achieved via better consumption – a more organic or energy-efficient consumption? Slavoj Zizek reminds us that to purchase an environmentally friendly product is also to acquire a certain ideological stance,40 a way to project a certain “authentic” image: “The very ecological protest against the ruthless capitalist exploitation of natural resources is already caught in the commodification of experiences: although ecology perceives itself as the protest against the virtualization of our daily lives and advocates a return to the direct experience of sensual material reality, ecology itself is branded as a new lifestyle.”41 . For Zizek the advances in sustainability have served mainly to bring the nature into the field of managerial accounting because the field of sustainability is entangled with the emergent economic concepts of Cultural Capitalism and Natural Capitalism. But at the heart of this problem is the rise of what Zizek calls “enlightened hedonistic consumerism” – the willing surrender of personal choice (in favor of the market’s socio-ecological responsible products) to produce a guilt-free consumption. Bjarke Ingels offers a different point of view on this matter. In a Ted talk in 2011,42 the Danish architect argued that Sustainability’s fundamental problem lies in its branding. The argument is that sustainability is too attached to a message of sacrifice and moderation when, according to Ingles, the hybridization between ecology and design should exacerbate the idea of human enjoyment. Hence, the architect introduces the concept of Hedonistic Sustainability, whose ultimate expression can be found on BIG’s Amager Bakke Waste-to-Energy Plant in Copenhagen – a power plant that doubles as a ski slope whose shape replicates a section of an actual Swedish mountain.

Unapologetic biomimicry: BIG’s Amager Bakke Waste-to-Energy Plant in Copenhagen © BIG-Bjarke Ingels Group.

There is hardly a better example of biomimicry: a building designed not only to look like a mountain but also to be used as a mountain. However, the project addresses our ecological predicament by projecting a (symbolic) message into the real, as an attempt to conceal the irreducible gap separating the real from the modes of its symbolization. Its meaning is precisely to have meaning, to be an island of meaning in the flow of our less meaningful daily life. A key notion here is Zizek’s concept of fetishistic disavowal: the pervasive collective attitude of passive acceptance (“I know very well but . . .”) of the adverse social and ecological consequences of our civilized society that make the smooth-functioning of everyday life possible by focusing on the pleasures by it provided.43 The project only creates the illusion that it is contributing to solving the ecological crisis, while, in reality, it is just keeping it at a distance by removing any traumatic notion of human behavior. To increase the levels of irony, the mouth of the chimney is designed to puff a gigantic smoke ring (30m in diameter) per 100kg of CO2. Ingels explains that “one of the drivers of behavioural change is knowledge (. . .) If you come to Copenhagen in 2016, you just have to count the smoke rings and when you’ve counted 10 of them we’ve just emitted 1ton of co2.”44 “Sometimes, the thing itself can serve as its own mask – the most effective way to obfuscate social antagonisms being to openly display them,”45 argues Zizek. The predicament here is self-evident. The waste originating from our unsustainable lifestyles is transformed into an object of desire and celebration. With this disarming approach, all tensions between humans and the environment disappear and, as the project provides the illusion of ecological justice, it does not require societal change. It eliminates any need for social change because it is in itself the materialization of the eco-social revolution we longed for. Sustainable architecture becomes an agent of political neutralization.

Critical Green

It is beyond question that environmental dilemmas will be the driving force for the evolution of architecture in the coming decades. However, green design’s self-projection as a beacon of hope for the restoration of a hopeful “natural balance” has led to the blurring and overlapping of the borders that separate the symbolic from the material and metaphor from reality. Additionally, by compulsively attempting to constitute a unified and totalized theory and practice, green design does not seem to realize the existing and widening gap between sustainability’s socio-ethical message and the material outcomes of its individual realizations, between the green rhetoric and the green buildings. To address the problems posed by this fragmented and polarized situation, rather than setting managerial-like goals or charging design with an “ultimate” lost meaning, sustainable architecture could attempt to do precisely the opposite: to accept the reality of the ecological crisis in its senseless actuality, to abandon the need for implementing a radical break from the rest of the unsustainable world, to liberate design from origins and ends. Green buildings will not save the world. Despite the substantial importance of the progressive designs here presented, the attempts to forge paths towards sustainability seem to depend not so much on the celebration of the ecologic accomplishments of isolated “pockets” of sustainability, but, instead, on the radical realization of the impossibility of a “Sustainable Architecture.” Sustainability is fundamentally about realizing the inexorable interconnectedness of the world, and therefore carries a genuine potential for an architectural engagement with politics. This opens the opportunity for a critical revision of the contemporary necessities and priorities within the architectural project, which cannot be carried out without engaging with design’s timeless condition of being an agent unremittingly subject and responsive to drastic processes of change and contamination, of which “nature” was always a part. Consequently, it may be by dissolving the archetypal architectural oppositions such as natural/artificial, local/global, traditional/progressive, technological/archaic or cultural/popular that we can finally relinquish the need for a drastic epistemological break or the pursuit of a “naturalized” aesthetic expression, and begin to formulate critical and divergent “recompositions” of architectural ecologies.