1. Introduction

The rise of China is one of the defining features of the post-Cold War era. Rapid economic transformation has propelled China to the centre of global politics, with leaders who are increasingly confident in advancing their interests and pursuing greater influence in the governance of the international system. In the same period, the EU extended to 28 Member States and deepened integration across an expanding array of policy domains. Foreign and security policy integration remains relatively limited and often beset by tensions, especially due to differing levels of willingness to use force and between pro-Atlanticists and those favouring greater European autonomy.1 Nevertheless, the search for a coherent set of collective foreign policies towards major international partners has been ongoing since the 2003 European Security Strategy identified select countries as ‘strategic partners’ – key interlocutors with whom cooperation would be a prerequisite for the attainment of the EU’s global objectives.

The UK has played a critical role in shaping EU–China relations; Brexit will weaken the EU’s collective power and shift the balance in China’s favour. European policymakers will need to take stock of the implications for the EU’s ambition to expand its role as an actor in East Asia. Brexit arrives at a moment when negotiations for an ambitious EU–China bilateral investment agreement continue, with an eye on an eventual free trade agreement. Simultaneously, the public record indicates that EU policymakers increasingly perceive challenges arising from China’s expanding global presence, exemplified by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and investment in European critical infrastructure. Aspects of China’s behaviour – particularly in the South China Sea disputes – test the durability of the rules-based order and have fostered further concern among European policy elites, leading to recognition that the EU’s approach needs ‘to be more realistic, assertive and multi-faceted’.2 As both the EU and China emerge as global powers, the significance of their relationship’s trajectory extends well beyond the bilateral context.

I analyse how the relationship’s contemporary dynamics are playing out and likely to evolve, with respect to the EU as a collective actor in the international arena. First, I assess the impact of Brexit on the relative power balance, specifically the EU27’s collective economic, military and political power, using quantitative and qualitative metrics. Thereafter, I review the ‘state of play’ in three crucial bilateral issues – the negotiation of a bilateral investment agreement; the development of the BRI and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB); and the ongoing South China Sea disputes – highlighting the UK’s preferences and input. I evaluate how the loss of resources and shifting constellation of preferences among the EU27 could affect the attainment of EU strategic objectives.

Following the Brexit referendum, the UK government was slow to articulate its vision for the extent of cooperation with EU on foreign and security policies.3 Indeed, the Political Declaration that accompanied the 2019 Withdrawal Agreement stated that the two sides supported ‘ambitious, close and lasting cooperation on external action’ and stipulated that ‘the future relationship should provide for appropriate dialogue, consultation, coordination, exchange of information and cooperation mechanisms’.4 This is slated to include a Political Dialogue on Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), along with sectoral dialogues. Selective participation in informal Ministerial meetings – at the invitation of the High Representative – was also outlined. The Political Declaration suggests an ad hoc cooperative relationship without structured, institutionalised participation in dedicated policy spaces. In a letter to Member States, the European Council Legal Service sought to allay concerns by asserting that the UK ‘as a third country, is not a party to any institutional deliberation at whatever stage’ and signalled its intent to remain ‘very vigilant in all future processes in which [there is] a need to protect the autonomy of decision-making of the Council’.5

At the time of writing (February 2020), how the future UK–EU relationship in the foreign policy domain will be operationalised remains indeterminate; however, this paper assumes that the UK and EU will cooperate informally when interests overlap. This will be limited to areas where the legal framework of the EU’s external relations permit non-members to participate (such as the CFSP and CSDP), therefore areas of exclusive EU competence will be off limits. The UK’s statement on negotiations on the future relationship with the EU stipulated that while cooperation in the foreign policy domain would endure, it would not require an ‘institutionalised relationship’.6 The EU’s negotiating mandate spelled out that the ‘envisaged partnership should preserve the autonomy of the Union’s decision-making’ and ‘respect the [EU’s] legal order’. While clear that there would not be an institutional framework – but rather, the existing legal framework is interpreted as permissive of UK participation in EU initiatives when invited – the document is significant as it holds open the door for cooperation on sanctions policy, collaboration with the European Defence Agency, and ‘on an exceptional basis’ participation in individual projects under the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) framework.7 The UK is explicitly identified as a third country, but one with which the EU envisages considerable scope for continued cooperation in the foreign, security and defence domains.

The departure of the UK from the EU is unlikely to disrupt the EU–China relationship. However, there are several key implications evident from the following analysis. The absence of the UK’s diplomatic service will be detrimental to the EU’s understanding of China, potentially impacting policymaking, too. The EU’s economic position relative to China will be weakened, decreasing its leverage in investment and trade negotiations. The EU’s ability to respond to the BRI and act collectively within the AIIB will be diluted. Finally, Brexit will curtail the expansion of the EU’s development as a security actor in the Asia Pacific, thereby limiting its input into the resolution of the ongoing South China Sea disputes. The EU is more than the sum of its parts, but to understand the EU collective, the capabilities and preferences of Member States in the foreign policy domain need to be examined closely. As will be shown, although before the referendum President Xi had indicated a preference for the UK to remain in the EU8 undoubtedly Brexit presents numerous strategic gains for the PRC.

2. Relative power in the EU–China relationship

Brexit will diminish various facets of the EU’s power, both in aggregate terms (individual Member States) and pooled (supranational) resources. Measuring what qualifies as ‘EU power’ is inherently complicated due to the limited nature of foreign and security policy integration, and the varied competences of EU institutions across issue areas. Nevertheless, aggregate measures can be useful proxies by encapsulating the collective’s potential/latent power. I present snapshots of the economic, military and soft power of the EU – with and without the UK – relative to China to give an idea of the altered balance.

2.1. Economic power

Economic power is the key component of the EU’s international presence. The existence of the Single Market and the common external trade policy entails that it is possible to treat the EU as a single economic entity for the purposes of international comparison. China’s economic performance has been critical to the development of its new-found political and military power. Although the EU–China relationship is much more than economic in nature, it is indubitably the central component. Comparing across standard measures of economic power – gross domestic product (GDP), GDP per capita, share of world GDP – we can draw inferences regarding the bilateral balance. Further, trade and investment figures – including bilateral flows of goods and services, trade balance, and foreign direct investment – help contextualise the extent of interdependence.

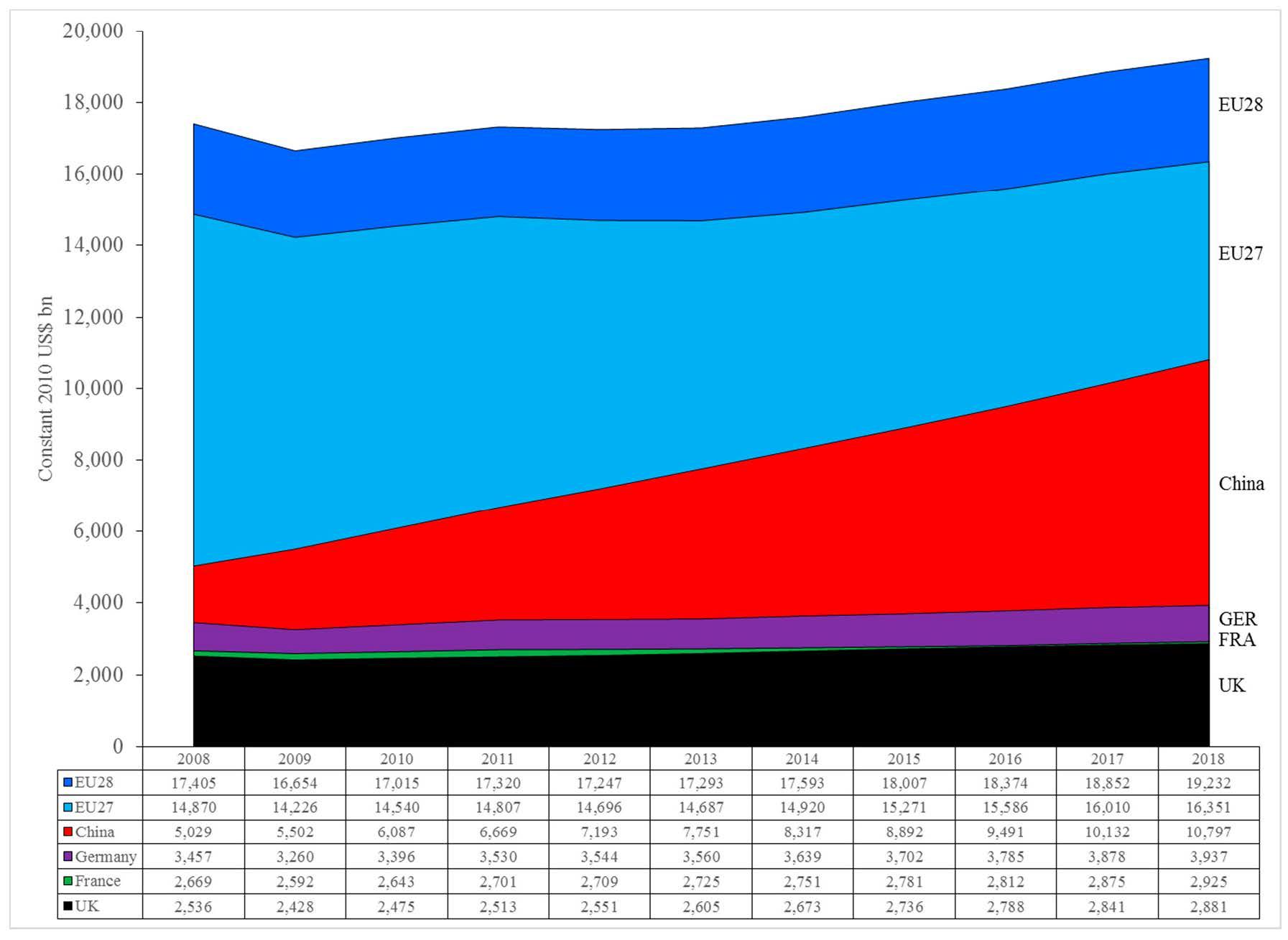

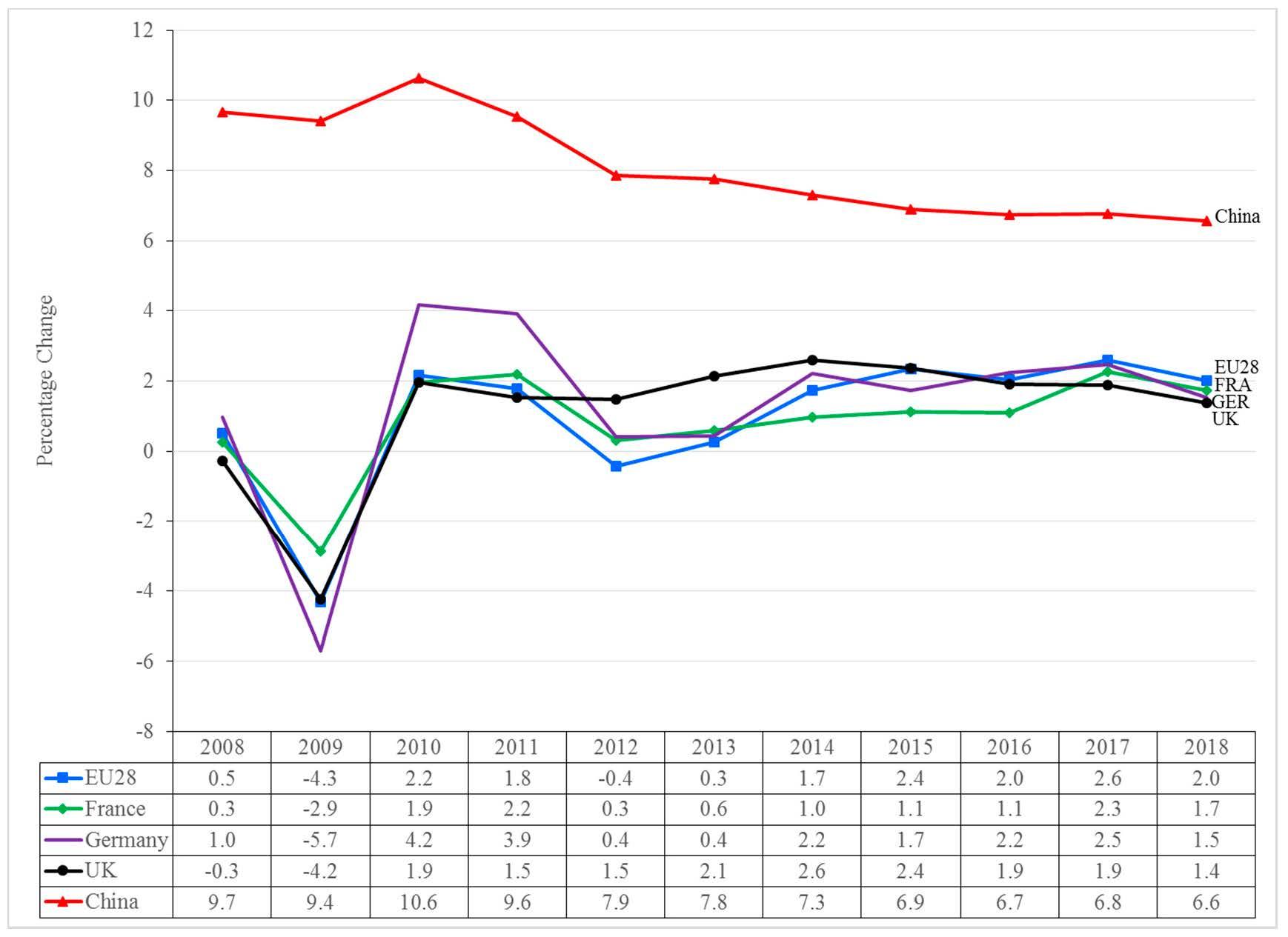

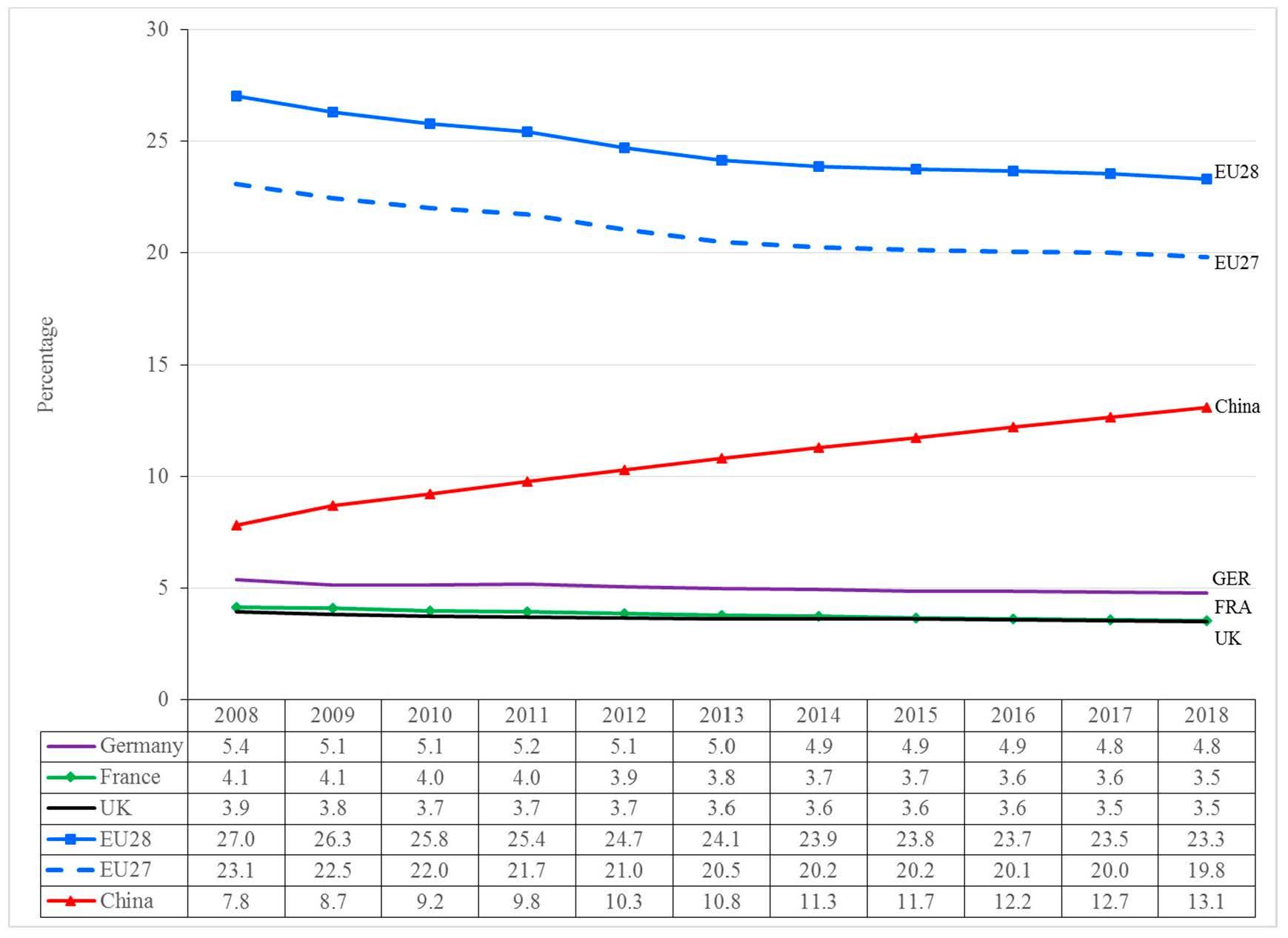

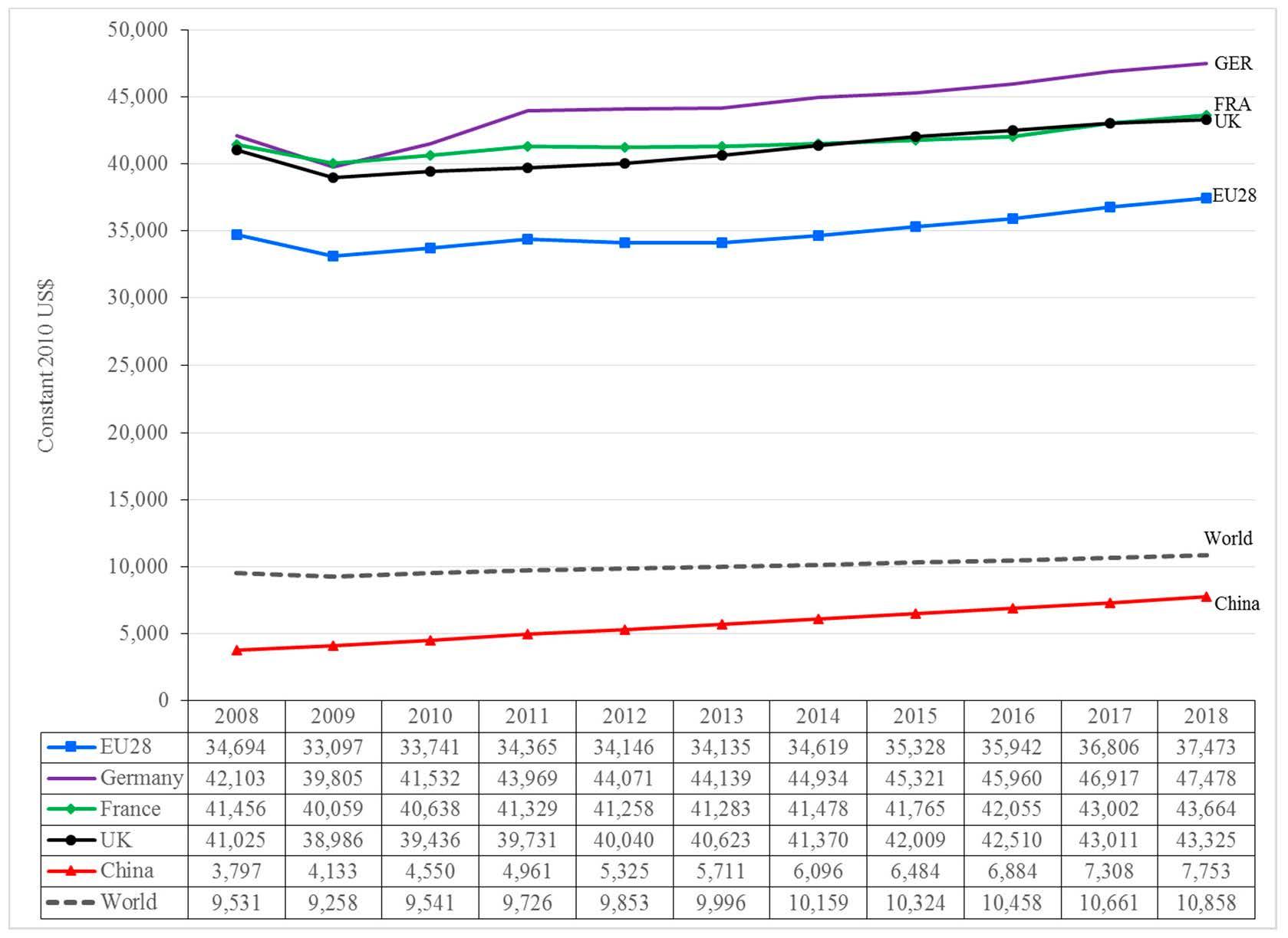

The EU’s aggregate GDP – even subtracting the UK – is substantially greater than that of China (Figure 1). The more telling aspect is relative change over time, with China’s rapid economic expansion – thanks in part to a comparatively low starting point – as confirmed by annual GDP growth rates (Figure 2). As a percentage of global GDP (Figure 3), the EU’s share has shrunk while China’s has grown; post Brexit, the relative gap will shrink further. Here, the relative balance of economic power remains in the EU’s favour, but it is nevertheless being eroded. The EU remains firmly ahead in terms of GDP per capita (Figure 4), entailing greater societal wealth, and so despite its overall economic success China remains a much poorer country, consistently below the world average: in 2018, China’s GDP per capita was ~71% that of the global figure; meanwhile, the EU28’s was ~345%. Although EU27 data was not available, given that the UK is consistently higher than the EU28 average, then ceteris paribus Brexit will cause a slight decrease in the EU figure. Regardless, the considerable gap between the EU and China is likely to persist on this measure.

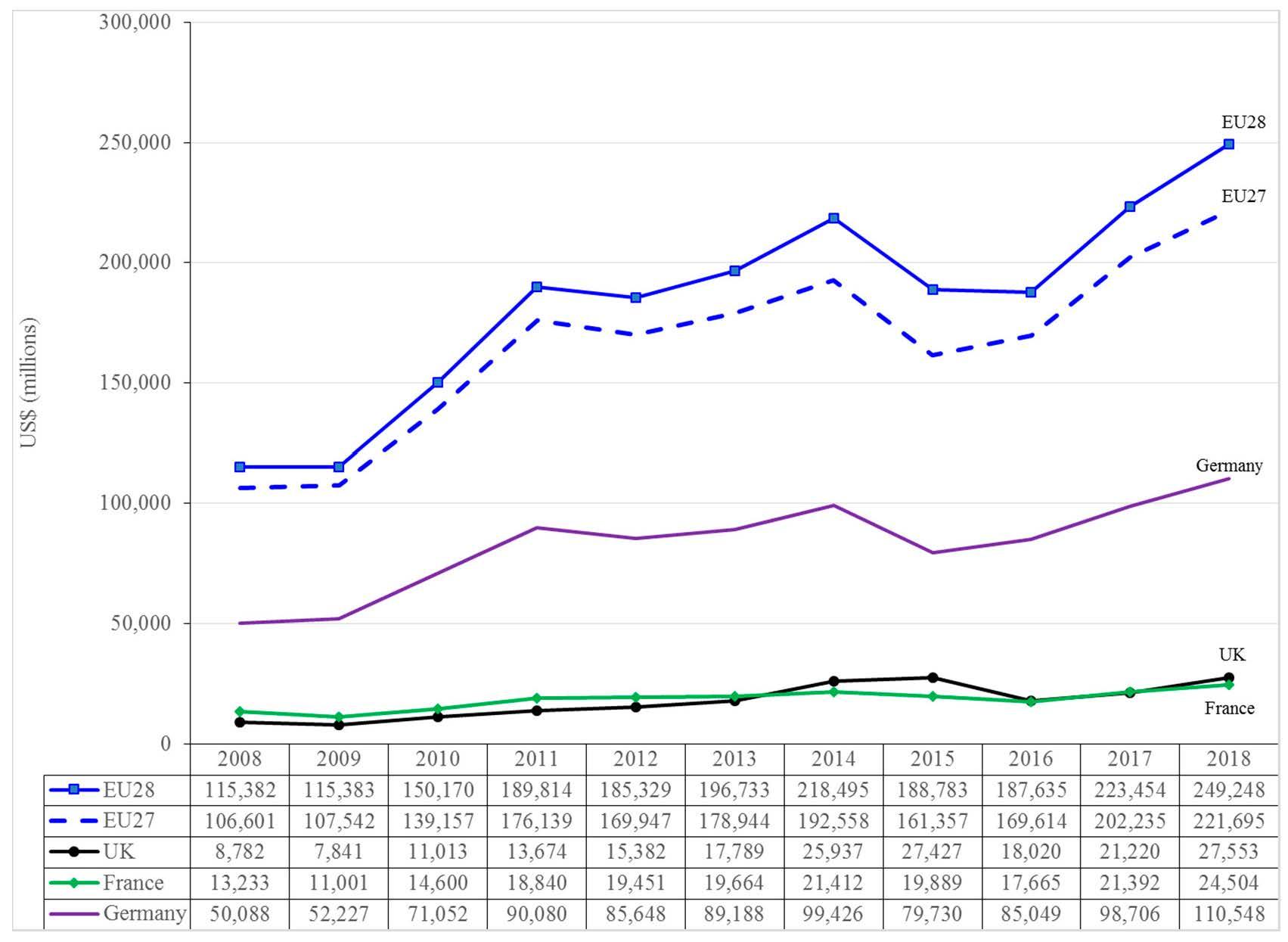

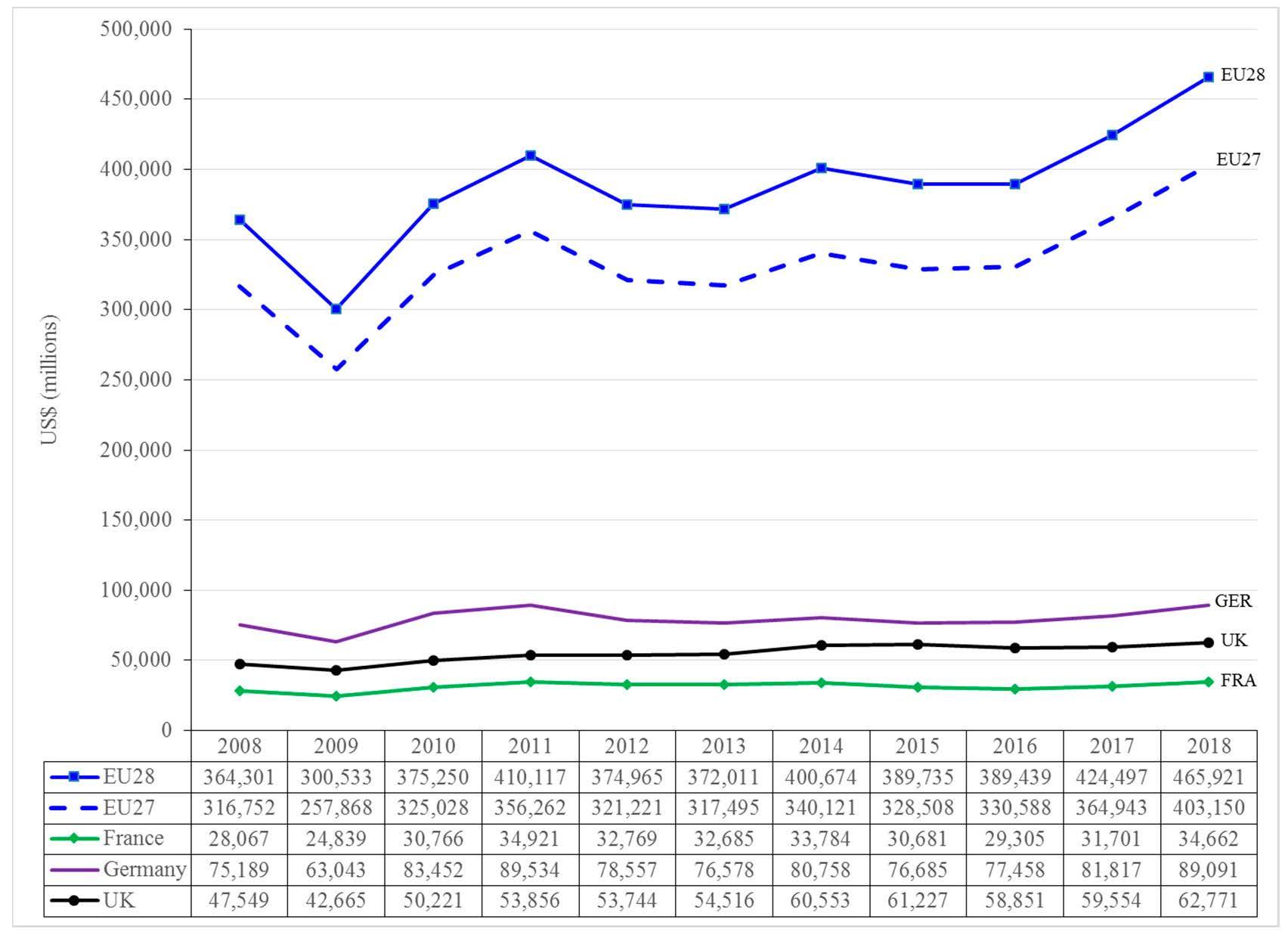

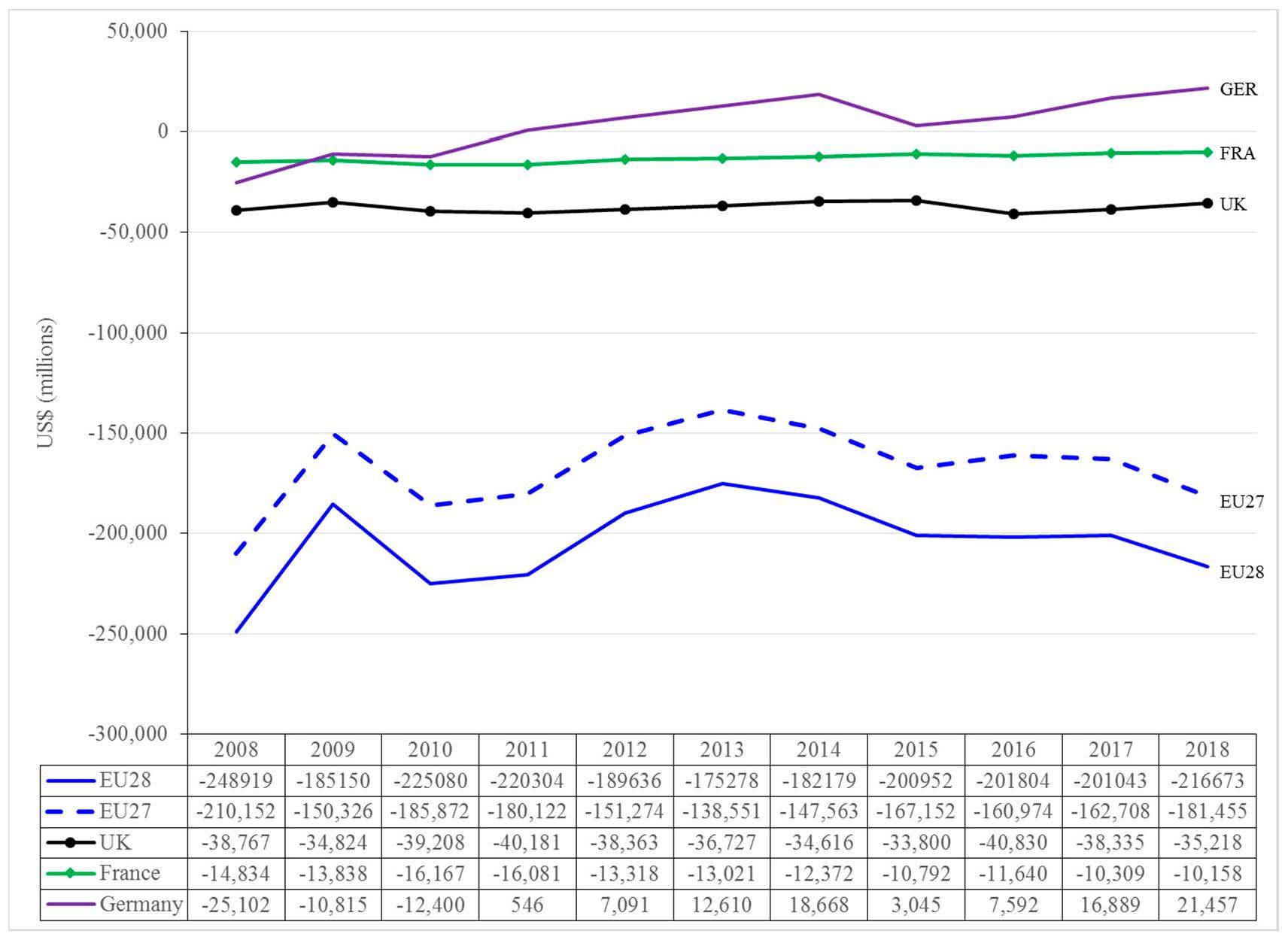

Turning to trade, the EU is China’s primary partner, while China is second to the US for the EU.9 The relationship is one of the world’s largest, and even without the UK, the EU is set to remain China’s most important partner. EU goods exports to China have grown over the past decade (Figure 5), although the UK’s contribution (11.1% for 2018) is small compared to Germany’s (44.4%). The gap is less pronounced for imports from China (Figure 6): in 2018, 13.5% of China’s EU exports went to the UK, behind Germany (19.1%). In the same year the UK received 2.4% of China’s global exports, whereas the EU27 took 15.3%. The UK is by no means an insignificant export destination, but the EU will remain far more important with a clear implication for where Beijing’s priorities will lie for future trade agreements. The EU and the UK run trade deficits with China (Figure 7), thus the absolute size of the deficit will decrease after Brexit – albeit the relationship will still be imbalanced in China’s favour. Overall, Brexit makes a slight dent in the absolute size of the trade relationship, but not the relative importance for either side. The story for the UK will be much different, having exited the sizeable EU bloc to face an economic superpower in China, hoping to come up with a favourable deal. The UK may have to come to terms with having ‘plutoed’ itself.10

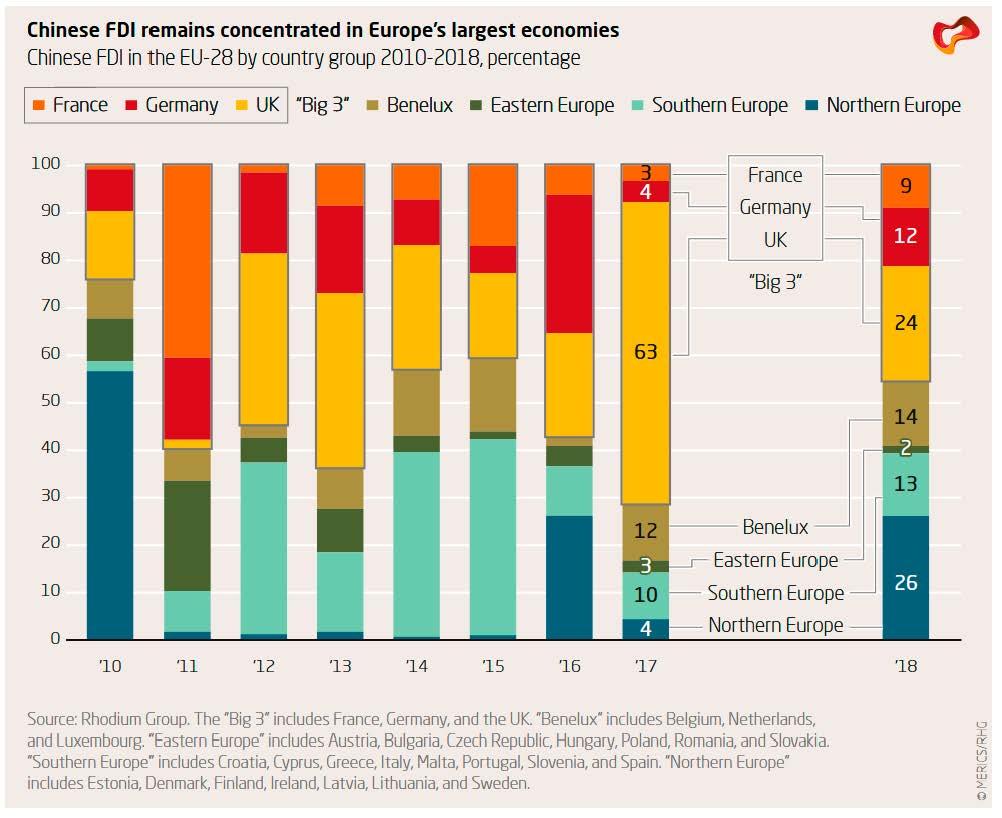

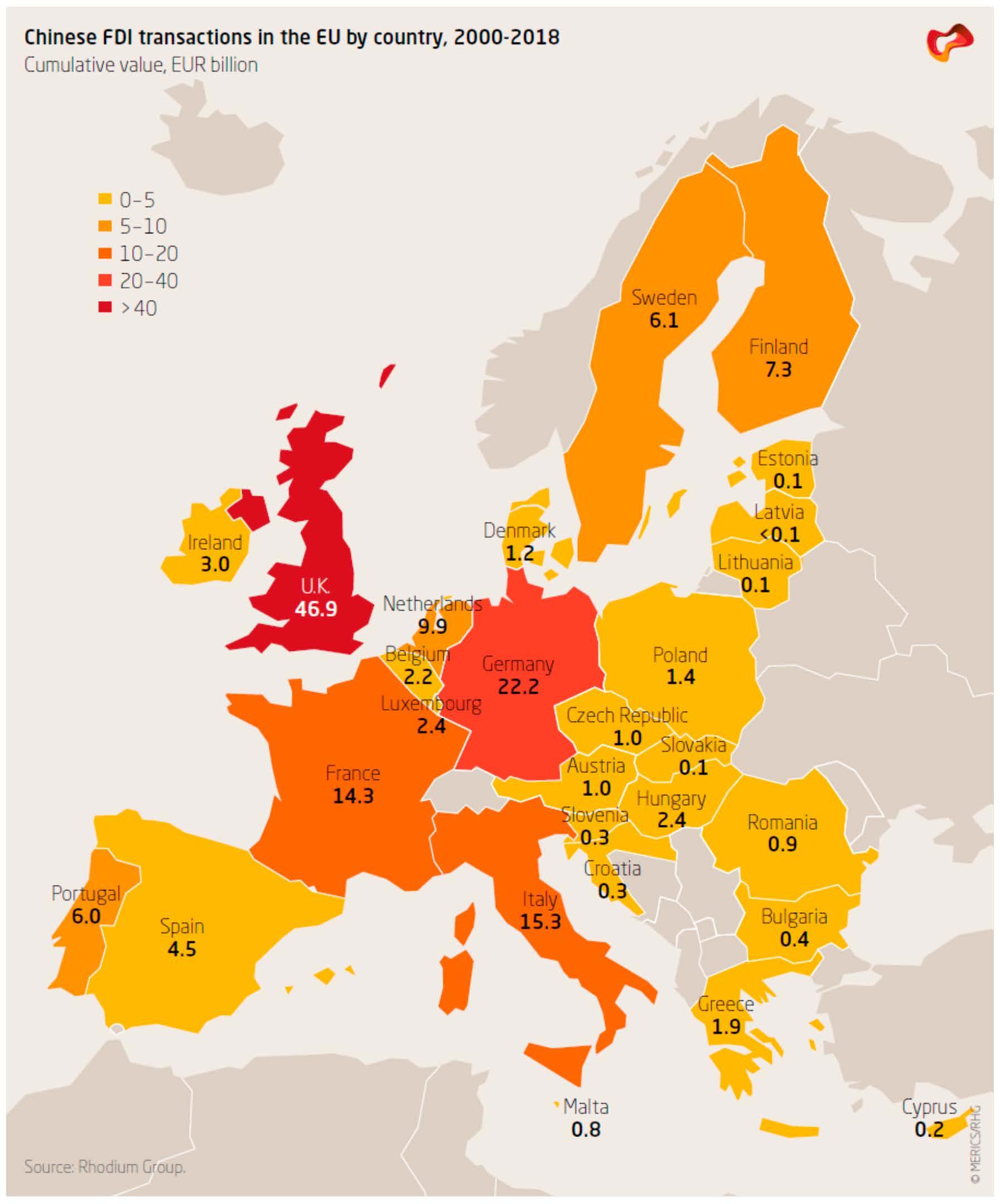

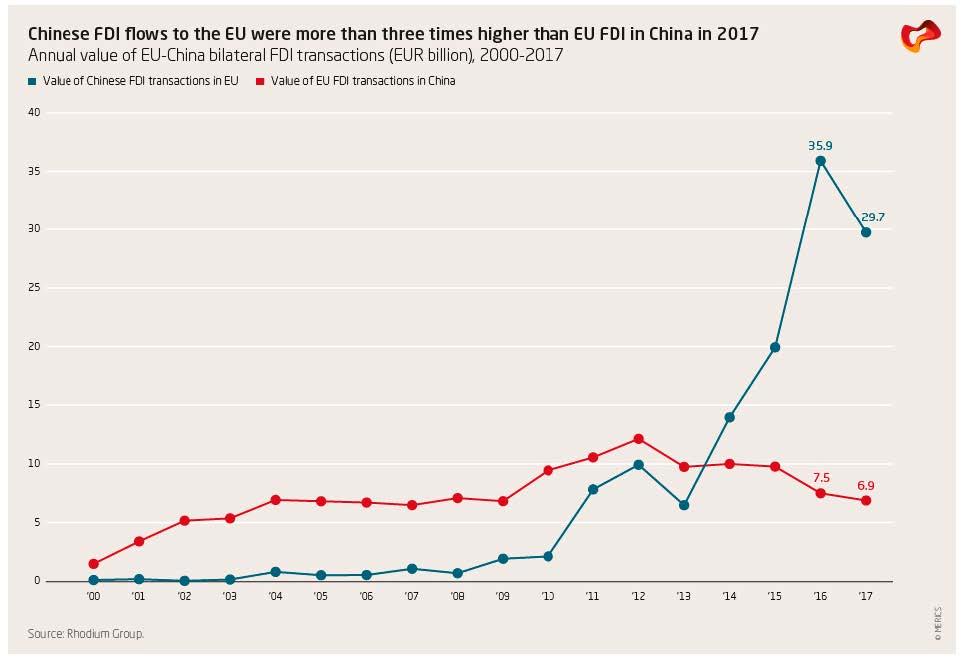

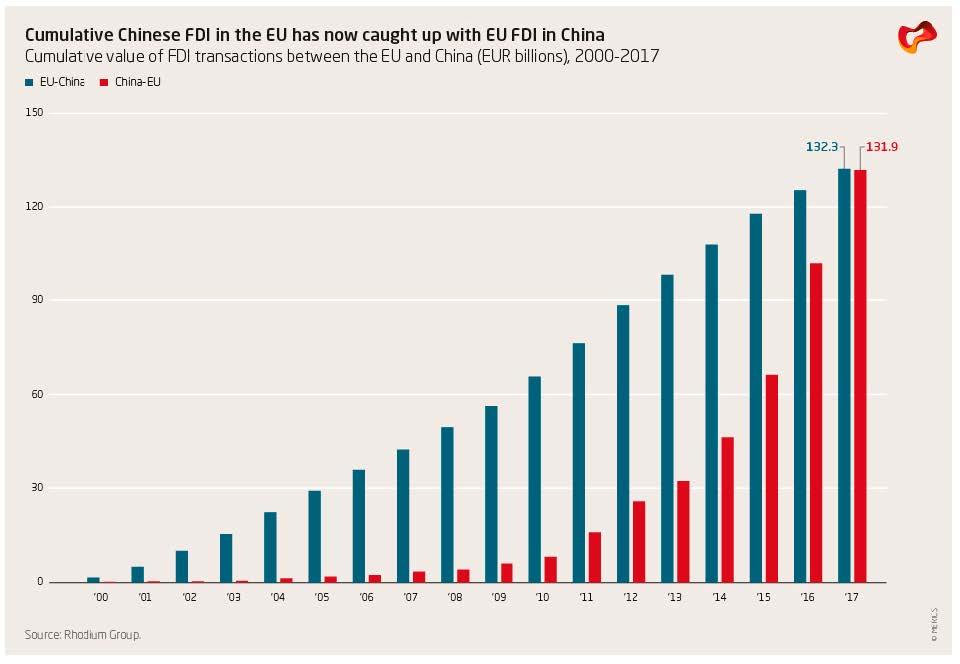

China’s Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Europe has increased significantly in recent years, which Meunier attributes to the European economic crisis not only creating new opportunities for Chinese investors (more assets and depressed prices), but also having contributed to ‘lessening political resistance and making Chinese FDI less controversial and more palatable than would have been the case in flusher times’.11 While the EU3 of France, Germany and the UK have accounted for a significant share, China also invested heavily in southern Member States, particularly during the Eurozone crisis. Figure 8 reveals the distribution of China’s FDI in the EU (2010–18) and Figure 9 shows cumulative FDI (2000–18). Both demonstrate the primacy of the UK as FDI recipient, with France, Germany and Italy as other notable destinations. The implication of Brexit in this sense will be to decrease the totality of China FDI into the EU. How attractive the UK remains for FDI post Brexit remains to be seen, although Dhingra et al’s analysis suggests that EU membership is a vital component of its appeal: ‘FDI in the UK is often motivated by the ease of selling to the high-income and nearby consumers in the rest of the EU.’12 However, the EU’s overall attractiveness from China’s perspective is unlikely to be affected. The EU stands to potentially benefit from the negotiation of a new bilateral investment agreement with China (Section 3.1), creating the possibility for greater two-way FDI flows. Figure 10 and Figure 11 show just how the balance has shifted in the bilateral relationship: Chinese investment in Europe has rocketed since the onset of the Eurozone crisis, whereas European investment in China has been falling since then. This has resulted in a situation where cumulative FDI in each other’s economies has reached parity. Europe is no longer the dominant actor in the context of their bilateral investment relationship.

2.2. Military power

I should clarify that in this analysis there is no expectation of military confrontation between the EU (or Member States) and China. I also avoid the assumption that intentions can be essentially inferred from capabilities, as espoused by some realists, for example Mearsheimer.13 Nevertheless, military power is still widely regarded as a component of ‘great power’ status,14 contributes to international prestige, and cultivates political influence. The Chinese leadership has prioritised the modernisation of the county’s military since the early 1990s and undoubtedly regards military power as a prerequisite for influence on the world stage.15 Consequently, the relative military standing between the EU and China is not insignificant. Further, the EU’s stated intentions of increasing its presence in the Asia Pacific – for example, to support the rules-based order in the South China Sea16 – implies that it conceptualises military power projection as one component of a broader toolkit of policy instruments at its disposal. In recent years, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has undertaken joint training exercises with Russia in both the Baltic and Mediterranean seas, and a solo live-fire exercise in the latter.17 The relative power balance between European and Chinese navies may come to receive greater political attention in the future if the frequency of these types of activities increases. Of course, the absence of a joint EU force is significant in this respect as common action of this type will require case-by-case agreements.

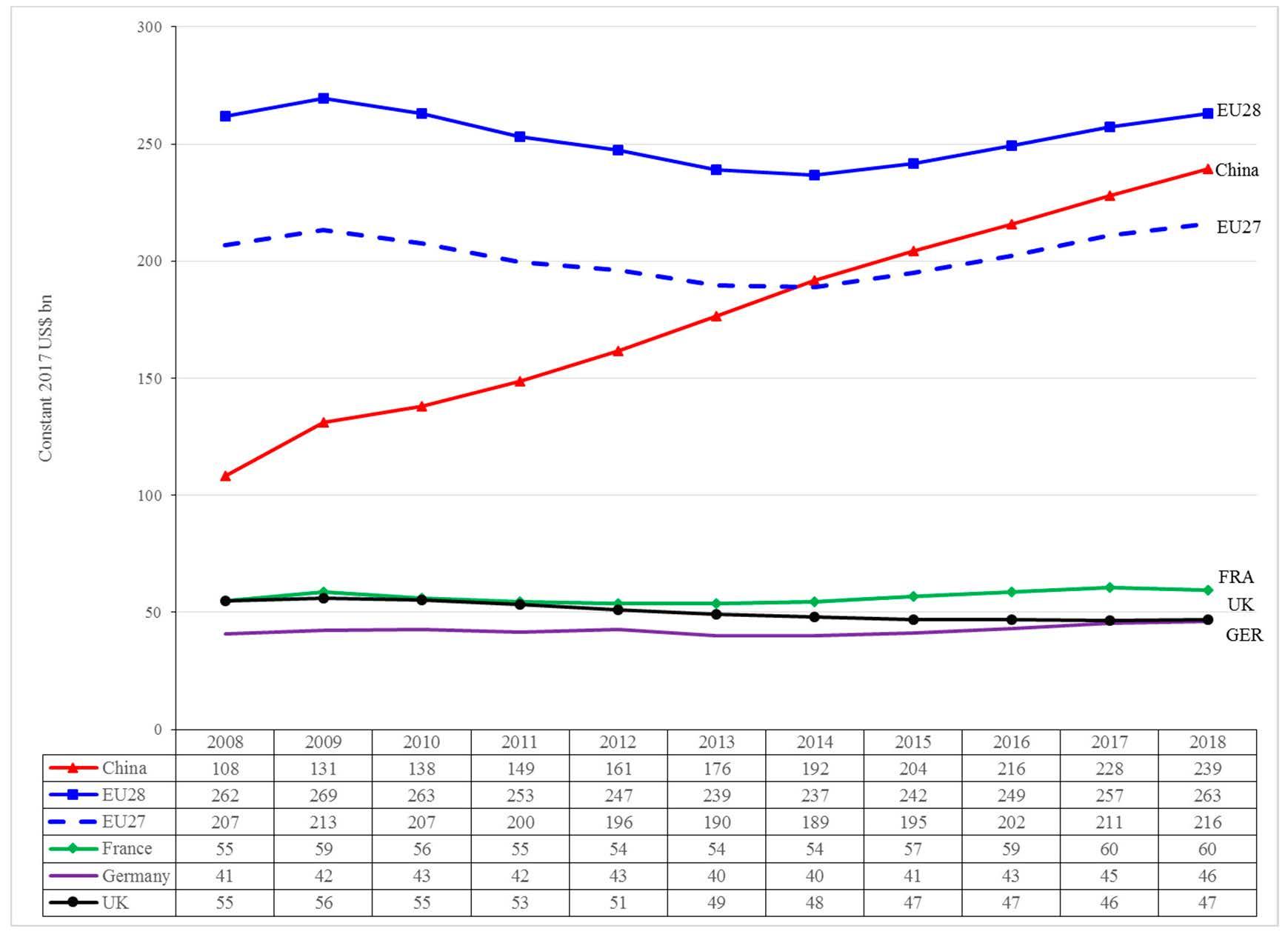

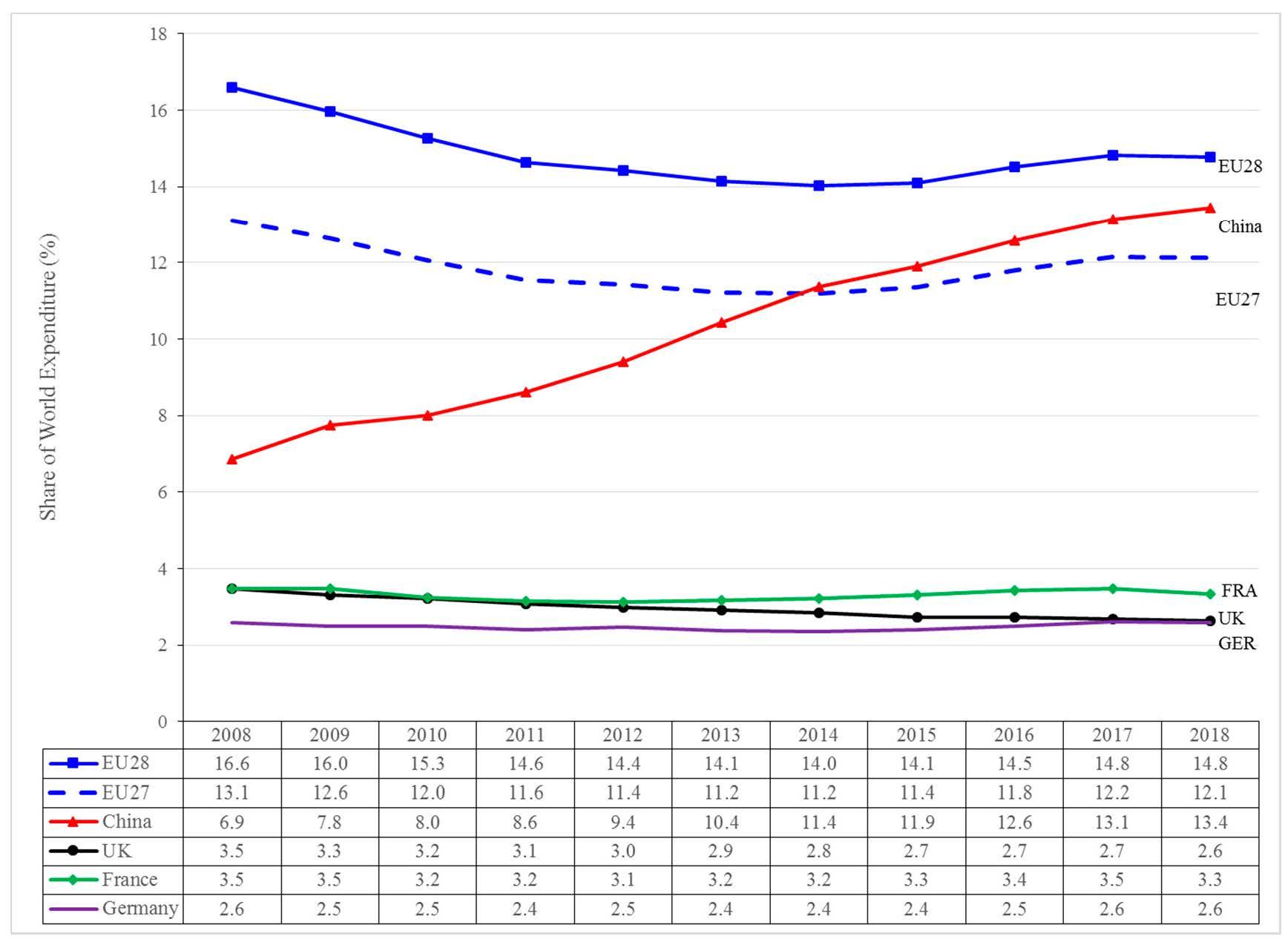

As a measure of input, defence expenditure18 on its own conveys little about power capabilities. However, trends over time can be indicative of the expected direction of national power (strengthening versus weakening) and of the level of political priority. Figure 12 displays trends in European and Chinese defence expenditure during 2008–18.19 An aggregate EU expenditure is presented to give an idea of what pooled resources look like, alongside individual defence budgets of the EU’s three biggest spenders – France, Germany and the UK.

China’s military defence expenditure more than doubled over the time period. By contrast, the EU28 in 2018 spent roughly the same as the EU25 in 2008.20 China’s military expenditure far outstrips any of the individual countries, though continues to lag the EU28. Modelling the EU without the UK, the EU27’s figures drop below China’s, indicating the UK’s importance to the overall picture of European expenditure; in 2018, it accounted for 18% of the EU28’s figure. While the UK will remain in NATO as Europe’s primary defence structure, Brexit presents a blow to the collective weight of the EU if it ever seeks to develop its security/defence presence through pooled resources. As it stands, the EU collectively constitutes the world’s second-largest military spender after the US; following Brexit, it slips to third. China’s share of world total expenditure has also been increasing as the EU’s decreases, but Brexit will see the EU drop below China on this measure sooner than it otherwise would have (Figure 13).

Table 1 provides a snapshot of select capabilities. A comprehensive overview of absolute military strength is beyond this paper’s scope; instead power projection capabilities serves as a useful heuristic for identifying which components to focus on. For simplicity, only the capabilities of the EU3 (France, Germany and the UK) are presented alongside China. What is immediately noticeable is that on certain capabilities, China is quantitatively equal to, or already pulling ahead of, the European powers. This is not to say that China’s capabilities are qualitatively equal, and its forces are less experienced than their European counterparts. Nevertheless, China has a greater baseline for undertaking power projection capabilities into Europe (should it choose to do so) than the reverse scenario. Of potential importance, China’s naval and air force capabilities would likely give Beijing the option of denying European powers the ability to deploy and operate within the Asia Pacific – if it perceived the need to do so.

China has already surpassed individual Member States with respect to the amount it is spending on its military capabilities and has been on a trajectory to overtake the EU collective. As defence expenditure and policy are still the domaine réservé of Member States,21 Brexit will have minimal impact on the actual defence situation, unless the UK’s economy suffers as a result and a political decision to cut back on expenditure is taken. However, the absolute balance of power between the EU (in aggregate) and China will shift towards the latter as the UK was one of the EU’s largest military powers in terms of spending, power projection capabilities and, in many regards, qualitative superiority. China’s capabilities have expanded from a low starting point at the end of the Cold War and it is increasingly closing the qualitative gap with European militaries, which have traditionally enjoyed technological and qualitative advantages.

2.3. Soft power

Lacking a dedicated hard (military) power presence, a common assumption is that the EU is primarily a soft – and even ‘normative’ – power.22 China, however, has amassed considerable soft power resources in recent years, translating its economic power into political power, but also increasing its diplomatic efforts and cultivating influence through persuasive means and efforts to project a positive image of China.

Various definitions of soft power exist, and cover a range of tools and attributes, some of which lend themselves to quantification and others which necessitate qualitative description. A full analysis of the components of soft power is outwith this paper’s scope. Handily, a composite measure of soft power has recently been developed to facilitate comparative analysis. This specific conceptualisation transcends the economic/non-economic components of foreign policy, grounding the concept in domestic characteristics that shape the actorness of States. Since 2015, Portland – the self-described strategic communications consultancy – has produced the Soft Power 30 index, which attempts to define and quantify soft power metrics. The analysis combines a variety of independent variables covering various aspects with different weightings.23 In the 2019 report 17 of the 30 were EU States – with France, the UK and Germany occupying the top three rankings.24 China ranked 27th, down from its previous best of 25th in 2017.25 The UK has ranked in the top two in all five years, holding the number one spot in 2018.26 While no combined EU weighting is presented, Member States’ dominance of the list is indicative of the soft power capacity which can be pooled or tapped into by the EU collective.

The Lowy Institute has developed a measure of the diplomatic reach of individual countries, which can serve as an indicator of soft power. The Global Diplomacy Index ranks the diplomatic networks of 60 countries based on the quantity of representations in third countries and multilateral organisations.27 Although the Index does not contain data on the EU’s delegations, 24 of the (then) 28 Member States are included, occupying four of the top 10 spots (Table 2). In 2019 China surpassed the US to take the top spot, with France in third. According to the European External Action Service (EEAS), there are 172 EU Delegations and Offices providing diplomatic representation to third countries and multilateral organisations.28 Incorporating this data, the EU places behind China and five Member States, but ahead of many others. Placed into the full Lowy Institute ranking, it would occupy 13th position, just behind India. Moreover, the EU’s delegations have carved out an interesting diplomatic role; while they ‘do not aim to replace or compete with EU member states’ national embassies’, they do conduct ‘traditional diplomatic practices and tasks in order to represent the EU’ and have added ‘the “extra-national” task of coordinating the European actors on the ground’.29 Arguably, the past decade has witnessed the development of the EU’s soft power diplomatic resources and enhanced the collective weight of its Member States. The unique character of the EU/European diplomatic networks transcends mere quantification.

Taken together, these two indexes reveal the EU’s substantial soft power advantage over China – largely thanks to the resources and status of Member States, including the UK. While China has now established considerable global reach that allows it to exert soft power, going by the Soft Power 30 index the extent of success is comparatively limited. Taking the UK out of the EU’s soft power equation will undoubtedly be detrimental for the EU, but it does not significantly alter the balance in China’s favour. The increased ability of the EU to coordinate Member State embassies in third countries stands to enhance its soft power further when the relevant diplomatic actors speak with a single voice.

2.4. Relative power standings before and after Brexit

In absolute terms, Brexit is not disastrous for the various facets of the EU’s power. Key States such as France and Germany will continue to contribute much to the economic, military and political (soft) power components of the EU’s aggregate strength, and the overall whole still puts the EU as one of the wealthiest and strongest actors in the international arena (usual caveats apply). The EU will continue to retain key advantages, such as the relative strength of the euro, technological advantages, low levels of corruption, and a free and open society where doing business is relatively easy. However, in the context of bilateral relations, if we assume that all other things remain equal in the trends observed above, the EU loses ground to China with the UK’s departure. This shifts the balance of power further in China’s favour, which may have implications for the negotiation of the bilateral investment agreement and, further down the line, a free trade agreement. The EU will have fewer capabilities at its disposal for influencing security dynamics in external regions, such as along the Belt and Road or in the Asia Pacific. China is, arguably, still rising, and thus its potential has yet to be fully realised. Any subtraction from the EU’s overall power decreases its standing relative to China. The UK is a significant loss in this regard.

3. Bilateral issues in EU–China relations

This section considers a selection of salient bilateral issues in the EU–China relationship. In each, I briefly outline the ‘state of play’ to provide contextual grounding, then identify the UK’s position/preferences and input into policy formation. I then contemplate how the issue will evolve post Brexit, considering how the EU’s position or ability to act may change, as well as whether the UK is likely to act independently towards China or in coordination with the EU where interests overlap.

3.1. Bilateral investment agreement

3.1.1. State of play

Negotiations on bilateral investment launched in 2014 and are shaping up as the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI).30 Due to limited progress in the political relationship since the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement negotiations effectively halted in 2011, there was hope among European policymakers that the CAI would provide an impetus for moving the bilateral relationship forward.31 A key goal for the EU is improving market access for investors in China, given the gap in investment openness resulting from ‘strategically limit[ed] access for foreign companies in many sectors and … rampant informal discrimination against foreign firms’.32

The EU–China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation – adopted at the 2013 bilateral summit as a framework for the relationship – emphasised the importance of the agreement for ‘securing predictable long-term access to EU and Chinese markets respectively and providing for strong protection to investors and their investments’.33 At the time of writing, the negotiations are ongoing; at the 20th EU–China Annual Summit in July 2018, the Join Statement identified the agreement as a ‘top priority and a key project towards establishing and maintaining an open, predictable, fair and transparent business environment’.34 In late 2019 the two sides indicated their intent to conclude negotiations in 2020.35 Notably, in policy documents and joint statements, the prospective agreement often features as part of the wider discussion around bilateral trade and investment, which is relatively easy for the two sides to agree on due to the dominance of economic issues in the relationship, an area where they can point to tangible results and goals.

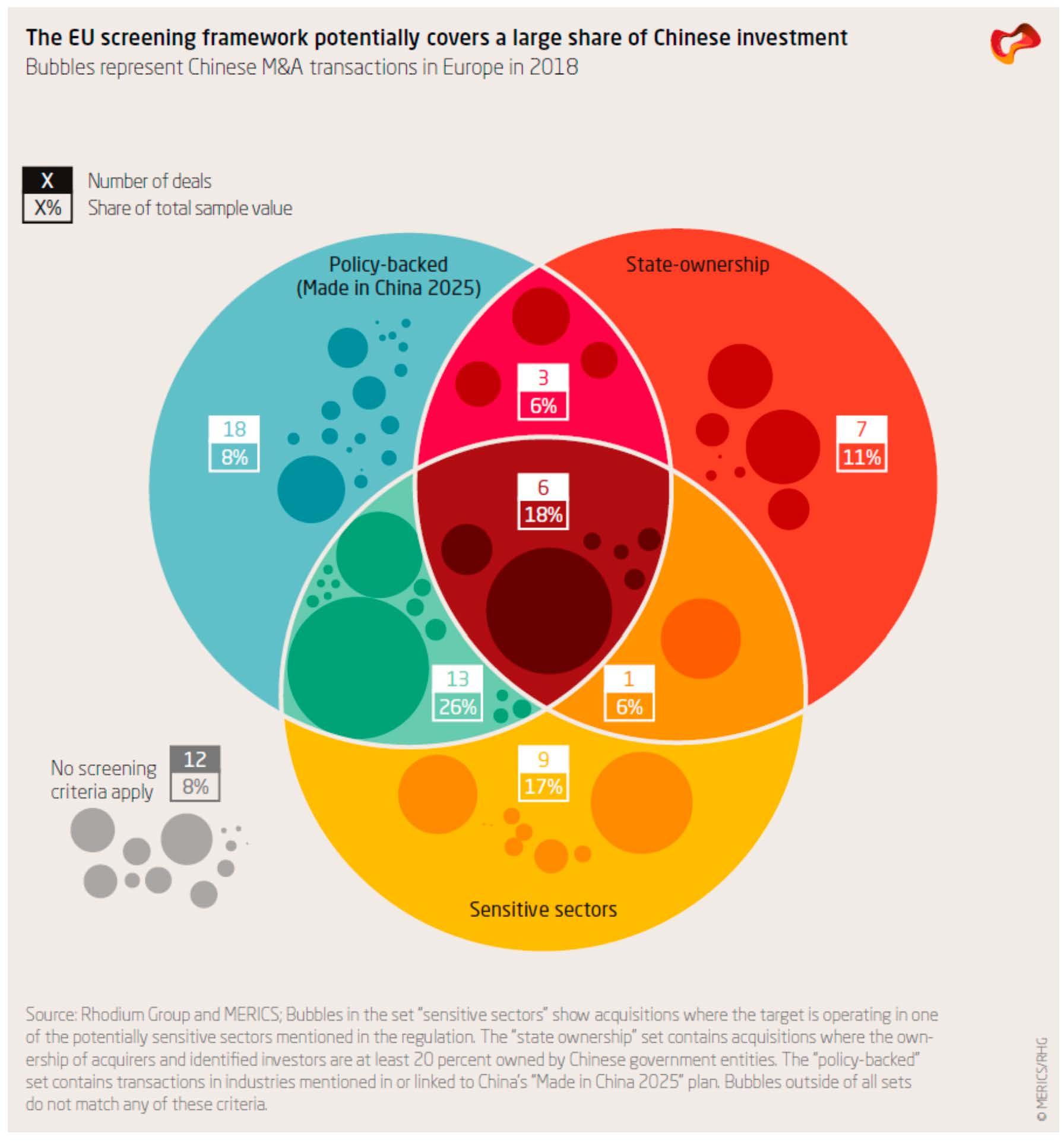

One issue that has emerged in recent years is the increasing attention on the security implications of China’s investment in Europe, especially with respect to high-end technology companies, often with strategic importance – such as robotics and sensors.36 In April 2019 the EU established a new screening system to ensure more robust consideration of FDI acquisitions to protect European security interests.37 This is not directed solely at China, but undoubtedly the country’s activities have been a catalyst for the creation of this new policy instrument.38 A report from the Mercator Institute for China Studies modelled the approximate potential application of the new screening mechanism based on Chinese inbound investments in 2018, finding that 83% of transactions would have been subjected to screening (Figure 14).39

Although some have suggested that the EU’s approach should keep the CAI negotiations on a separate track from the FDI screening mechanism,40 the EU cannot control how China will respond. It is possible to imagine a situation in which China slows or pulls back from negotiations in response to these new measures if they are perceived by the government as directed at, or discriminating against, China. This may open new fault lines among EU actors – between those who feel the need for greater monitoring of FDI acquisitions and those who want to see a more liberalised regime that encourages greater Chinese investment. At the time of writing the CAI negotiations had proceeded through 25 rounds,41 with Brexit seemingly having no adverse impact on the timetable.

3.1.2. The UK’s position and input

The UK had been a strong supporter of the CAI, owing to the prominence of financial and investment services in its domestic economy that would stand to benefit from increased access to China’s market. As Figure 8 and Figure 9 revealed, the UK is one of the top European destinations for Chinese FDI, alongside France, Germany and Italy. Consequently, while an EU member, the UK had strong reasons to support an improved investment relationship with China. Increased market access would increase investment opportunities for the UK’s finance and high-tech companies.

Since 2010 the Conservative Party-led governments have consistently adopted a stance of opening both the UK’s and European markets to China. From 2012 onwards, Chancellor Osborne was largely driving the UK’s China policy, advancing economic gains while side-lining political issues such as human rights.42 Explicit support for the advancement of the CAI was expressed on several occasions, although public statements are the most illustrative. In a 2015 joint statement, Prime Minister Cameron and President Xi pledged to ‘enhance bilateral trade and investment, and support mutual economic competitiveness and innovation’, committing to create ‘a fair, transparent, positive and business-friendly policy environment for two-way investment and addressing business concerns regarding market access and regulations’.43 With reference to the EU level, the statement confirmed Cameron and Xi’s ‘support [for] the early conclusion of an ambitious and comprehensive China-EU Investment Agreement, and call for the swift launch of a joint feasibility study for a China-EU Free Trade Agreement’.44

In the months following the Brexit referendum the new Prime Minister, Theresa May, appeared to signal a cooling of the UK’s positive disposition towards China by pausing finalisation of a deal for investment in the nuclear energy sector. Hinkley Point C, a planned nuclear power station, was to be part-funded by Chinese investment, alongside France. Potential security concerns had been flagged by some,45 which Cameron largely sidestepped. Ultimately, however, May’s government approved the deal with no further public scrutiny of security concerns. By this point it was known that the UK would leave the EU, therefore shifting attitudes in the UK were unlikely to influence other EU actors. The government’s subsequent pronouncements indicated that China will be a priority for the UK post-Brexit, with May and Xi announcing a joint trade and investment review in 2018.46

The UK is moving forward with proposals to modify its own FDI regime to allow for government intervention in merger deals where national security is perceived to be at stake. The government has collected feedback on a set of proposals set out in a white paper to inform future primary legislation.47 Although the UK has been one of the most favourable to the liberalisation of trade and investment in relations with China, there now appears to be a reconsideration of its priorities just as it leaves the EU.

3.1.3. Post-Brexit outlook

China already has bilateral investment treaties with all EU Member States, except Ireland.48 The Lisbon Treaty conferred competence for FDI to the EU, as part of the Common Commercial Policy (Article 207 TFEU).49 A new EU bilateral agreement would supersede these, while UK–China arrangements will continue as before unless there are separate negotiations for an updated version. Operating outwith the collective negotiating power of the EU, the UK would be unlikely to have the ability to extract concessions around market access. In light of comparative market size, the EU will be unlikely to perceive the UK as a competitor in seeking Chinese investment, therefore its approach to negotiations with China is likely to remain unaltered in that respect. While Brexit shrinks the EU’s market and shifts the relative balance slightly in China’s favour, it is unlikely to diminish the perceived importance of the European market for Chinese policymakers and businesses. The post-Lisbon competence over investment policy enjoyed by the Commission is important because ‘bringing trade and investment matters into the same hands contributes to ensuring the development of a strong, coherent and efficient external economic policy’;50 this is the far more significant factor when considering the EU’s capacity vis-à-vis China. Consequently, Brexit presents a new set of challenges to the UK–China investment relationship, but less so the EU–China one. The EU and the UK will still have overlapping interests with respect to addressing China’s market restrictiveness – according to the OECD, China remains one of the most closed nations for FDI51 – therefore coordinating their approaches to negotiations would be mutually beneficial, even if the logic of competition wins out in reality.

3.2. Belt and Road Initiative and the AIIB

3.2.1. State of play

As major foreign economic policy initiatives of Xi Jinping’s presidency, the BRI and AIIB are often touted as evidence of China’s ambitions to play a more prominent role in the world, including global economic governance. The BRI was announced in 2013, and the AIIB in 2014 as the former’s main funding vehicle. Reactions from individual EU Member States have varied but, on the whole, they were – at least initially – positive about both initiatives.52 In theory, most would benefit from the BRI at a minimum by virtue of Single Market membership and the improved trade connections between China and Europe, but there would also be opportunities for inward infrastructure investment from the BRI for the poorer Central and Eastern European (CEE) States. Those with the economic resources could contribute to the AIIB’s funds and participate in its governance as China deliberately sought to make it an international institution. Europe is the main ‘endpoint’ of the BRI, reflecting China’s recognition of the importance of the European market as an export destination. Both initiatives present clear opportunities for the EU, not just economically but also in terms of creating new opportunities for closer political engagement with China. However, both initiatives also spawn new challenges to the EU–China relationship, not least because of the concern that China could be seeking to ‘extend to a large part of the world its model of development both political and economic’,53 thereby undermining the EU’s self-styled role as a model for others to emulate.

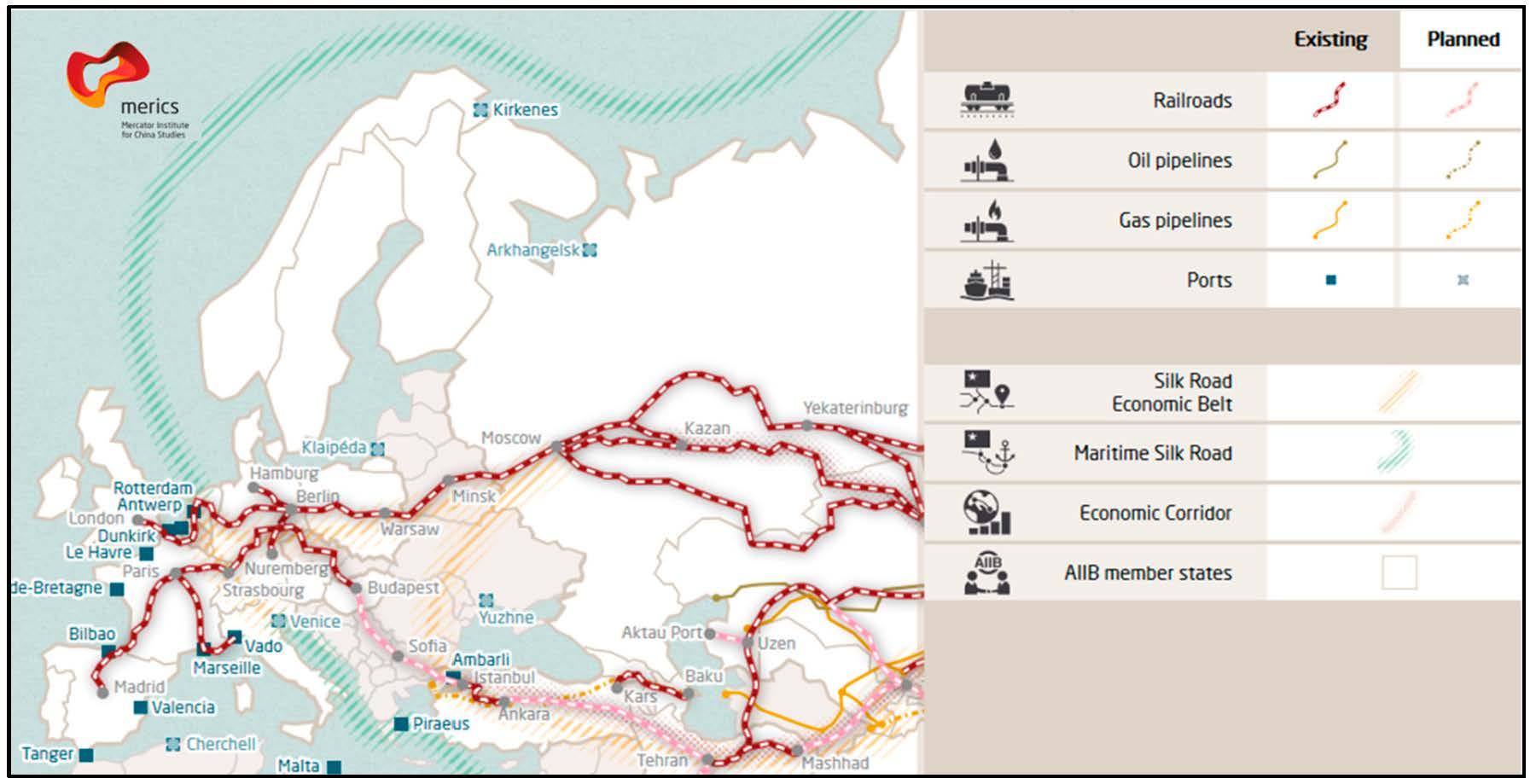

What exactly qualifies as part of the BRI remains somewhat ambiguous; even its geographic scope has expanded since first launched, with connections to Latin America now included under the term.54 The BRI lacks a specific legal framework, differentiating it from a traditional free trade agreement, and participation is open rather than exclusive.55 The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development cites an estimated ‘US$900 billion in projects … already planned or underway’ as of 2017.56 Figure 15 illustrates the European end of the BRI, plotting both existing and planned infrastructure networks. We can see that most EU States will be directly impacted by the creation of the BRI, provided the vision is implemented as intended. Inevitably, the BRI has become an item on the EU’s external relations agenda.

The EU has been relatively slow in reacting to the BRI, with Member States formulating their own positions. As recently as the 2018 Munich Security Conference, calls for a unified EU response to the BRI were voiced by Germany’s Foreign Minister Gabriel, France’s Prime Minister Philippe, and Commission President Juncker.57 Undoubtedly, the fact that some Member States perceive greater opportunities than others makes forging a common position more difficult. In April 2018 the ambassadors from EU States in Beijing worked on a document that was to critique the BRI; the leaked version asserted that the project ‘runs counter to the EU agenda for liberalizing trade, and pushes the balance of power in favour of subsidized Chinese companies’.58 However, the Hungarian ambassador refused to endorse the document, ending the initiative.59 Hungary has been one of the main recipients of Chinese investment among the CEE countries,60 with the Budapest–Belgrade high-speed railway – part-funded by Chinese enterprises – a significant component of the development of the BRI in Europe.61

In September 2018, High Representative Federica Mogherini unveiled the new Connectivity Strategy paper,62 widely accepted as the EU’s policy response to the BRI63 – although the official position is that it is complementary rather than oppositional. When asked if the intent was to challenge China, Mogherini responded that ‘[o]ur proposals, our policies and our calendar are not determined elsewhere … It is not a reaction … to another initiative’.64 The paper indicated that the EU is not offering simply a competing source of funding, but a qualitatively different approach to ‘connectivity’, emphasising environmental sustainability, digital infrastructure, promoting mobility and securing the interests of residents of areas undergoing infrastructure development.65 The vision laid out arguably resonates with the major and minor norms claimed to be at the centre of the Normative Power Europe model,66 which embodies the notion that the EU represents a distinct type of value-driven international actor.

References to the EU’s successful internal market are used to frame the logic behind the values- and rules-based approach to connectivity. The externalisation of the EU’s internal practices is thus offered as a proven, reliable approach to achieving objectives shared with Asian countries.67 China is mentioned only a few times – primarily in relation to cooperative endeavours68 – although the BRI is conspicuous by its absence, other than affirmation that the EU would work to ‘strengthen the existing cooperation on the respective infrastructure and development cooperation initiatives’.69 However, the strategy seems more aspirational than substantive, lacking details on specific future projects or financing. That the title stipulates that the document contains ‘building blocks for an EU strategy’ is indicative of its embryonic status.

As of December 2019, the UK and another 19 EU Member States are AIIB members; although the EU is not represented this collective presence is not insignificant, accounting for 21.4% of the voting power (when including the UK – 18.5% without) (Table 3). Only China has a greater share of voting power (26.7%) and the next-closest individual countries – India (7.6%) and Russia (6%) – lag some way behind (albeit holding more than any one EU country). Neither China nor the EU has enough votes to wield an institutional veto. In terms of subscriptions paid to the AIIB, the EU (20.4%, 17.3% without the UK) trails China (30.8%) despite greater relative wealth.70 However, since some EU actors have been pushing for a collective policy on the BRI, it is not out of the question that the very nature of the AIIB as a vehicle for funding projects may entail cooperation, including voting in the Board of Governors.

The EU has been well represented within the AIIB’s senior management team. The bank’s president, Jin Liqun, is a Chinese national but three of the original five vice-presidents were from the EU – specifically, France, Germany and the UK.71 The organisation’s Chief Risk Officer is currently a German national. Although these individuals work for the AIIB as private individuals rather than national representatives, they nevertheless could offer an avenue of influence for their home governments (and potentially the EU) to some extent. Their own professional backgrounds, in theory, could help with the process of translating European values and standards into the practices of the AIIB. Yet the institution is still in its infancy, and there have been few real tests of its governance standards to date. The extent to which European presence within it will shape its operations – and thereby influence the implementation of the BRI – remains to be seen.

3.2.2. The UK’s position and input

The UK has generally been supportive of China’s efforts with the BRI and was proactively engaged with the establishment of the AIIB. President Xi’s 2015 UK visit resulted in a joint statement endorsing cooperation at the UK–China and EU–China levels:

Both sides have a strong interest in cooperating on each other’s major initiatives, namely China’s ‘Belt and Road’ initiative and the UK’s National Infrastructure Plan and the Northern PowerHouse. They will further discuss a UK-China infrastructure alliance under existing mechanisms and explore cooperation in light of the China-EU Joint Investment Fund and Connectivity Platform.

In the same statement, the UK’s support for the AIIB was reiterated: ‘[The UK and China] look forward to the AIIB’s early operation and integration into the global financial system as a “lean, clean and green” institution that addresses Asia’s infrastructure needs.’73 At this time, the UK government was fully committing itself to the notion of a ‘golden era’ in bilateral relations, driven by Chancellor Osborne, who viewed economic engagement as the only viable path.74

While the UK has been a strong supporter of both the BRI and AIIB, many other EU Member States are equally (or more) enthusiastic. The UK acting as ‘first-mover’ on AIIB created pressure for other EU Member States to quickly follow suit, but these governments were already considering membership. There is little evidence to suggest that the UK has shaped EU collective positions on either of these issues to any real extent, even as an enthusiastic proponent. Those EU Member States that stood to gain most from investment through the BRI – the CEE countries – have embraced the plan even more strongly. The institutionalisation of Chinese coordination with 17 States75 known as the ‘17+1’ format is evidence of the extent of China’s growing influence in Europe. The UK government had not made any specific effort to direct the evolution of this new partnership, despite its apparent influence with many of these States.

3.2.3. Post-Brexit outlook

With respect to the AIIB, Brexit will have almost no direct implications unless the EU members eventually opt to coordinate their activities within the institution but exclude the UK. Still, it would be in the UK and EU’s interests to cooperate to increase their collective leverage. If China reneges on its stated commitment to uphold international standards of transparency and rules-based governance of the AIIB, then the European actors would be compelled to band together. In this hypothetical scenario, Brexit would not preclude UK–EU cooperation.

With the UK out of the EU, the latter will have fewer resources at its disposal for the implementation of its Connectivity Strategy although it remains possible that, depending on the negotiated future UK–EU relationship, there may be opportunities for the UK to cooperate with specific projects. Even if this is the case, it is unlikely that the Connectivity Strategy will rival BRI in scope or speed of implementation. The BRI already has a head-start of over five years, and it is not clear what appetite there will be for EU initiatives if China is already financing projects, particularly if there are additional regulatory restrictions around environmental standards. The Connectivity Strategy was notably lacking in detail of funds that will be committed, a key detail that will likely be revealed with future EU budgetary plans. Consequently, the EU’s commitment to following through on this strategy has yet to be tested.

On the BRI, Brexit does not necessarily entail greater coherence between the remaining EU Member States. The division between the larger States – particularly France and Germany – and the 17+1 group with respect to their openness to China’s investment in national infrastructure is likely to persist. The UK was often perceived as a counterbalance to the Franco-German duo in EU foreign policy and held influence with the CEE States due to common pro-Atlanticist leanings. Absent the UK, the larger, Western States might encounter greater obstacles to exerting influence over these States, especially if the latter perceive economic opportunities presented by China as lucrative enough to ignore attempts to build a collective EU response to the BRI.

If, as Rolland argues, the BRI must be understood as part of China’s ‘grand strategy’ designed to facilitate an ‘unimpeded rise to great-power status’,76 then the EU needs to go beyond the Connectivity Strategy and have a plan for ensuring that China’s great-power behaviour is compatible with the rules and dominant norms in the international system. This task will be more daunting as the EU is unlikely to have the means to influence China’s relationships with neighbouring Asian countries. Without the UK – still a significant diplomatic actor in its own right – contributing to such efforts, the EU’s efficacy will be further reduced.

In the AIIB, the collective presence of the EU will drop, with a reduction in voting power and a smaller share of the overall financial contributions to the bank’s funds. While it is possible that other EU States may join and make up for this to some extent, it is unlikely that their combined contribution would equal that of the UK. Any future efforts at policy coordination – and attempts to use their economic and institutional voting weight to influence China and/or the direction of the bank itself – will be less effective than if the UK were fully engaged. Again, it remains possible that the UK and EU would seek to informally coordinate in such instances, even in the absence of a formal agreement, but it cannot be guaranteed.

The UK’s post-Brexit plans have placed considerable emphasis on the need for strong trade relations with China. Prime Minister May publicly stated support for participation in both the AIIB and BRI, for instance in January 2018 while meeting with Premier Li:

[The UK welcomes] the opportunities provided by the Belt and Road Initiative to further prosperity and sustainable development across Asia and the wider world, and as with the Asian infrastructure investment bank, the UK is a natural partner for the Belt and Road initiative with our unrivalled City of London expertise … the UK and China will continue to work together to identify how best we can cooperate on the Belt and Road initiative across the region and ensure it meets international standards.

Despite this, the UK’s support for the BRI is not unconditional. During the same visit, it was widely reported that May refused to endorse the project in a formal memorandum of understanding due to concerns about the implementation and political objectives.78 Yet, to date, the UK government has not established a clear BRI strategy unlike the EU, US, Japan and India,79 potentially leaving it vulnerable to having a reactive rather than proactive approach in this dimension of its post-Brexit relationship with China. Whether the government under Boris Johnson will do so remains to be seen, but it is clear that the immediate post-Brexit agenda is dominated by negotiations on the future UK–EU relationship, and a potential trade deal with the US.

3.3. South China Sea disputes

3.3.1. State of play

In recent years the South China Sea disputes80 have drawn greater international attention as China becomes increasingly confrontational and as the US and others attempt to manage the situation by insisting on rules-based resolution.81 China asserts its sovereign claims through extensive island-building upon existing maritime features – a practice which has harmed the local environment – and deploying military assets to both existing and new islands under dispute. China has ignored adverse legal rulings, and in the absence of willingness among third parties to use military force to evict it from the claimed territories, is likely to continue to do so. Its ability to coerce other disputants has increased via its expanding capacity to project military power throughout the region. The South China Sea is a potential regional flashpoint that could draw in outside powers.

To date, the EU has played a relatively minor role in this dispute. The 2016 Elements for a New European Strategy for China document stipulated an ambition to proactively increase engagement in the Asia Pacific.82 The 2016 Global Strategy claimed the EU had a role as a ‘global maritime security provider’, identifying a key objective to ‘further universalize and implement the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, including its dispute settlement mechanisms’.83 While the EU has clear interests linked (directly and indirectly) to the situation in the South China Sea – continued trade flows, regional stability, adherence to the rules-based international order – its policy responses have been relatively limited and somewhat inconsistent. This is most clearly illustrated by the watered-down response to the Hague Tribunal ruling on the Philippines v China case in July 2016, when China’s historical-based sovereignty claims were ruled inadmissible.84 The High Representative, on behalf of the EU, supported binding arbitration before the ruling took place.85 Following the ruling, a new declaration noticeably omitted reference to the ruling as legally binding upon the two sides.86 Thanks to its economic leverage, China ‘soften[ed] the resolve’ of several Member States, with Greece, Hungary and Croatia effectively supporting its position.87

That the EU took three days to produce its response to the ruling and ended up with a less firm stance than it had previously adopted indicates the coordination problems facing Member States, illustrating the outsized influence of smaller countries motivated by economic interests. Some Member States have sought to influence the disputes outwith the EU structures, most prominently those with the capacity to project power into the region. Although at one time France had proposed a collective EU commitment to support the US in the region by undertaking freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) to underline that the territories remain in international waters,88 the lack of interest from most other Member States has seen the country opt for cooperation with the UK.89 In 2019, France reiterated a commitment to sail its warships through the South China Sea at least twice per year, while German officials reportedly remain split over any such actions.90

The disputes themselves remain a ‘live’ issue, with no progress towards a mutually acceptable solution emerging. Rather, China continues to change the material reality with its extensive militarisation efforts. In August 2018 the Philippines’ President Duterte – who initially pursued closer relations with China – publicly pushed back on the latter’s behaviour in the South China Sea, stating that he hoped ‘China would temper at least its behaviour’, warning that the potential for conflict between the US and China remained real, as ‘one of these days, a hot head commander there (could) just press a trigger’.91 Meanwhile, the US shows no sign of backing away from its approach of FONOPs, thus the status quo looks likely to persist.

3.3.2. The UK’s position and input

Although the UK has had virtually no regional presence since Hong Kong’s 1997 retrocession, arguably it has vested interests in the South China Sea disputes by virtue of its UN Security Council membership, close partnership with the US, its desire to support the rules-based order, and the possible threats to trade flows. Yet through much of the period when the disputes – and China’s island-building and militarisation activities – were intensifying, the UK remained relatively quiet. This has been attributed to the Conservative-led government under Cameron prioritising economic relations and adopting an accommodating stance on political and security issues.92 There were almost no independent statements made by senior figures in the government, instead the UK preferred collective responses from the G7 and the EU – but it was not a driving force behind these. At the 2016 G7 Summit, Cameron explicitly called for China to respect the (then-upcoming) Hague Tribunal ruling, ostensibly after being criticised by the US for the UK’s accommodating approach.93 Between the summit and the ruling, Cameron resigned from the office of Prime Minister.

Prime Minister May appeared to take a more resolute position as part of a broader strategy of reasserting the UK’s role as a global power, at a time when many predicted that Brexit would ultimately diminish its international role. Under May’s government, the UK has deployed Royal Air Force units to the region for overflight missions in the disputed territories,94 conducted FONOPs and pledged to cooperate with France on future operations,95 and committed to deploy one of its new aircraft carriers to the Pacific once fully operational.96 The UK’s 2018 FONOP led to criticism from China Daily, a State-controlled newspaper, warning that the agreed exploration of a post-Brexit UK–China free trade deal could be in danger as an ‘act that harms China’s core interests will only put a spanner in the works’,97 indicating that China is taking notice of the UK’s renewed regional activism.

3.3.3. Post-Brexit outlook

Since the implications of the disputes are mostly an indirect concern for Europeans, it seems likely that they will remain a relatively low priority – particularly compared with the CAI and BRI, which have palpable direct implications for European interests. The Elements for a New European Strategy on China barely referenced the disputes, and that was drafted and adopted prior to the July 2016 ruling, that is before the divisions between Member States undermined efforts to develop a unified approach. The EU is still searching for a policy on the South China Sea, and any actions in the immediate future will be carried out by Member States independently or in concert with select partners. The EEAS’s director of security policy, François Rivasseau, admitted that the EU was ‘not there’ in terms of contributing to FONOPs, although argued that it was ‘not entirely out of the question’ that this may change.98

France and the UK are, for the time being, likely to remain the only active Member States on this front. During the 2018 Shangri La Dialogue, the two countries announced joint exercises in the South China Sea.99 So far, the UK’s impending departure from the EU has not disrupted the Franco-British cooperative efforts in the South China Sea, and the two sides have reaffirmed their intentions in this regard. Within the EU, France is confronted by Member States that are deeply reluctant to become involved with the disputes to any extent beyond issuing declarations, are reluctant or unable to project power into the Asia Pacific, and a few that are, essentially, aligned with China’s position. Absent a realignment of political preferences or a rapid deterioration in the situation in the South China Sea whereby the EU is forced to pick a side, then France is unlikely to find support for its initiatives.

As the UK looks to shore up its reputation as a global player in the face of questions about the negative impact of Brexit for its international standing, it will continue to play the role of a cooperative partner for France. In the event that the EU does unite round a common position on the South China Sea and launches joint regional missions, there is no reason why this would preclude EU–UK cooperation, especially given that the UK’s regional presence will likely already be established by that point. The main obstacle will be the UK’s sensitivity to China’s threats to walk away from a post-Brexit trade deal if it continues to involve itself in the disputes; while France has the economic weight of the EU behind it, the UK will be more exposed to China’s pressure when it is seeking new trade deals.

4. The EU’s China strategy: Shifting internal dynamics, intensifying external challenges

The UK’s departure from the EU will not fundamentally alter the nature of the EU–China relationship but it will produce some notable effects. Primarily, the trio of France, Germany and the UK that has been the powerhouse of many aspects of EU foreign policy will be replaced with a central Franco-German axis. The number of large EU States willing and able to occasionally stand up to China politically and/or rebuff it diplomatically will be reduced, entailing that the internal balance will shift slightly in favour of the smaller Member States that are more accommodating of China and susceptible to the exercise of economic leverage. With respect to the EU’s soft power capacity, that the UK had shifted towards an accommodationist approach since 2012100 arguably further undermined the prospects for a normative stance towards China. Consequently, Brexit could facilitate the leveraging of soft power resources by the EU to pressure China on human rights. To date, there has been little evidence that the remaining EU States are inclined to do so. More pressing from the EU’s perspective are the external challenges it is facing with respect to China’s continued rise and the adjustments that the EU needs to make in order to develop a coherent and feasible strategy. As Callahan observed, those examining EU–China relations need to ‘switch from asking how the EU can socialize China, to consider how European leaders need to work with a Beijing that is trying to socialize Europe’.101

The power dynamic between the EU and China – across economic, military, and political/soft power domains – is already shifting in China’s favour, even though on many measures it lags considerably behind. The UK contributed much to the EU’s overall power standing; Brexit will only push forward the date at which China surpasses the EU collective on most metrics. As Maher noted, owing to the UK’s material and political clout, Brexit ‘will likely have some effect over both Europe’s willingness and its ability to project power beyond its borders’.102 While this does not immediately threaten the EU or force a policy rethink, it will necessitate a recalibration of the EU’s strategy towards China. Steps have been taken in this direction with a new ‘strategic outlook’ paper produced by the Commission and High Representative and presented to the European Council in March 2019.103 This document garnered much attention for its rhetoric on China, describing the country as a ‘systemic rival’ at one point – although less noted was the continued emphasis on the two remaining strategic partners.104 However, the Council did not adopt this paper as a new China strategy, therefore the 2016 paper remains the official framework.105 Nevertheless, the document evinces a shift in thinking towards China and may yet serve as the basis of a new strategic approach that recalibrates the EU’s policy.

Even before Brexit, Germany was arguably the most important of China’s EU partners, both in terms of the scale of their economic relationship and Germany’s political leadership – this will be further accentuated post Brexit. France and Germany are generally more closely aligned when it comes to policy positions with respect to China106 and so the UK’s departure will diminish the range of preferences among the Member States with the greatest capacity to influence policy direction. Absent the UK, France is unlikely to find much support from other Member States for a more proactive naval presence in East Asia, or specifically the South China Sea. The existing Franco-British bilateral frameworks for military cooperation – particularly under the Lancaster House Treaties of 2010107 – create the possibility that the two could opt to act in concert. If this transpires, then operations will continue as they are presently playing out, but the symbolism of a unified presence will be weakened insofar as one of the two naval forces can no longer be designated as acting under the EU umbrella.

The EU faces outstanding problems managing its relationship with China. First are the continued disagreements between Member States over how to handle relations, most clearly identified by Fox and Godement108 and supported by other recent research.109 This curtails the development of a coherent strategy to guide policy decisions. Second is the growing influence of China within Europe, using economic leverage to extract political concessions, particularly among those in the 17+1 group as recipients of funding and assistance under the BRI umbrella. Third, like it or not, the economic relationship with China is vital and cannot be put aside and compartmentalised. Fourth, the EU alone will struggle to influence China, especially on the BRI and the South China Sea disputes. There are real limitations to the EU’s power. Brexit does not help with any of these four factors, but neither does it inherently exacerbate them.

Brexit may, however, present an opportunity for the EU27 to enhance and accelerate foreign policy integration. As Whitman noted, the UK ‘opposed reforms proposed to the CFSP during the Amsterdam, Nice and Lisbon Treaty negotiations which would have strengthened decision-making within the [Common Foreign and Security Policy]’.110 If the EU does opt to integrate further in this domain, then there may be a strengthened process by which strategies for third countries such as China are generated. This will not automatically produce a strengthened strategy for China or guarantee that differences between Member State preferences can be overcome. More foreign policy-related competences delegated to the EU level, and possibly the expansion of qualified majority voting to a greater array of foreign policy areas, could expedite policy formation processes, facilitating speedier responses to changing circumstances in the bilateral relationship with China.

China’s growing political influence in the EU is likely to have more of an impact on the constellation of Member State preferences than Brexit, if the smaller CEE States continue to prioritise attracting investment and infrastructure projects. Had the UK remained in the EU, the challenge to recalibrate strategy towards China in the face of shifting preferences among Member States would have been largely the same, except for the UK lending its political influence to support France and Germany, who are increasingly in favour of a more cautious approach. The external challenges posed by China’s ability to challenge the status quo of the international order in Asia through the BRI, creation of the AIIB, growing military power and de facto control of the South China Sea all overshadow Brexit in terms of implications for the EU–China relationship. The key implication of Brexit is that it detracts from the EU’s ability to respond as effectively as it would have had the UK remained a fully engaged actor at the centre of EU foreign policymaking.

5. Conclusion

China is on a trajectory to emerge as one of the world’s pre-eminent military, economic and political powers and may eventually displace the US and the EU entirely. Although the EU cannot (and does not presently seek to) disrupt this trajectory, it still needs to adapt its approach to China faced with this new reality. Brexit moves forward the point at which China overtakes the European bloc, thus the EU needs to react even more quickly. Brexit does not fundamentally disrupt the EU–China relationship but has significant implications. First, the UK’s contribution to the collective understanding of – and policymaking with respect to – China will be missed by the EU institutions. Few Member States rival the size of the UK’s diplomatic service, which has built up considerable expertise in dealing with China – even if this often side-lined in favour of chasing economic incentives. Second, Brexit weakens the EU’s relative economic standing, decreasing its advantage in negotiating investment and free trade agreements with China. Third, it reduces the EU’s ability to formulate and implement responses to the BRI and dilutes the collective power within the AIIB. Fourth, and most notably, the ambition for the EU to become a security actor in the Asia Pacific – and contribute to the maintenance of stability in the South China Sea – is drastically impacted. The most likely vehicle for European influence in this regard will be Franco-British cooperation that has emerged in the absence of an appetite among other Member States to become involved and the blocking of a more forceful EU stance by smaller Member States that are swayed by the economic opportunities vis-à-vis China.

The EU will need to adjust to the dilution of its international influence and recalibrate its strategy in light of its reduced capabilities and global reach. From China’s perspective, the UK’s need for trade and investment deals to deliver on the supposed ‘promise’ of Brexit could open new economic opportunities. Further, it may also create opportunities to set the UK and EU in competition against each other, thereby extracting more concessions that are favourable to China’s interests than would have been possible in the face of a 28-strong EU with the UK continuing as part of the core ‘EU3’ alongside France and Germany. From the UK’s perspective, it now finds itself in a considerably weaker position when facing China, having lost the ability to influence the EU bloc in line with its preferred policy options.