In October 1979, Margaret Thatcher’s Secretary of the Environment, Michael Heseltine, announced that a Holocaust memorial would be erected on public grounds in London.1 The media reported that it was the first major memorial representing the British Jewish community and the Holocaust, and that it was long overdue. News sources stated that the memorial would be built along Whitehall, on Richmond Terrace, next to the Ministry of Defence and near the Cenotaph.2 After the memorial’s announcement, the Secretary of State for Defence, Francis Pym, wrote to Heseltine, “I seriously object to the selection of the Richmond Terrace as a site. … It would be rather a strange newcomer to a part of London where the existing memorials … relate very much to the British national tradition and our own victories and sorrows.”3 Pym’s objection reveals in no uncertain terms that Jews were considered an ethnic minority and not considered culturally British. His opposition parallels that from many sources; most of Thatcher’s ministers expressed reservations about the project in private memoranda to Heseltine and Thatcher, stating that Crown Land was only suitable for “British” monuments.4 Indeed, between 1979, when the Prime Minister endorsed the memorial, and 1983, when it was completed, various government ministers opposed the memorial, citing issues of British identity, heritage, and foreign policy.

Accordingly, this article examines the Hyde Park Holocaust Memorial as a case study to illuminate questions of “Britishness” and Jewish identity at play at this historical moment. By analysing the politics surrounding the memorial, its proposed site, and designs in its political context, I argue that the Memorial reflects an attempt by a British ethnic minority, the Jews, to mark the tragedy of the Holocaust publicly while simultaneously staking a claim on British space in order to belong. However, as I shall demonstrate, the spatial politics at the crux of this debate resulted in an unsuccessful and inconsequential memorial because there was no meaningful attempt by the Jewish community or the government to assess or express how Holocaust memory belongs within British national space.

Over the four years of planning the memorial, debates about site, design, and politics reveal a mindset that saw Holocaust commemoration as unrelated to British history. The planning and discussion from this period raise issues about what counts as British history, how that history is represented, and, ultimately, who is publicly recognized as British. First, the memorial’s placement raises several questions. Does a Holocaust memorial belong in public spaces devoted to centuries of British history? Framed in the language of memorials, to whom does the public space belong? Which British subjects have a right to representation in the public space? If a Jewish memorial does belong in the public space, where should it be? Second, discussions about the memorial’s aesthetic reveal that the Jewish community wanted to make a memorial that was aligned with contemporaneous Holocaust memorials in other countries. This demonstrates a desire on the part of British Jewry to insert Britain into an international conversation of Holocaust commemoration at that moment, and concurrently reveals the government’s conflict about participating in that exchange. Ultimately, the government’s decision to limit the memorial’s design and build it in a secluded area of Hyde Park demonstrates a rejection of the idea of expanding the definition of “Britishness” and national memory.

These issues raised by the Hyde Park Holocaust Memorial Garden intersect at the points between “Jewishness” and “Britishness” in postwar Britain. While the memorial came to fruition under Thatcher’s government, the impetus to build a Holocaust memorial came directly from the Jewish community. When the memorial was being built, Britain was already experiencing rising tensions among its ethnic minorities, including former colonial subjects along with Jews. Many were beginning to seek and expand the definition of what it meant to be a British citizen, not merely holding a passport and exercising the right to vote but being seen as culturally equal. While this discussion focuses on a particular ethnic minority – British Jews – the government’s reservations about building a “Jewish” memorial are not a reflection of antisemitism; rather, they represent a more general desire to shield the British national landscape from any diversity.5 British Jews’ place as an ethnic minority in Britain is further complicated by looking at the place of contemporary Jews in Britain and the current rise of antisemitism. The sociologist Keith Kahn-Harris posits that antisemitism in 2020s Britain is perpetuated because antiracist groups and educators define Jews as a religion and thus refuse their right to self-identify as a race or ethnicity. Kahn-Harris believes that identifying Jews only as a religion becomes a veil for antisemitism to hide behind, because if being Jewish consists only of belonging to a religion, then antisemitism cannot be racism.6 British Jews lobbied for this memorial as a means of being more fully included in the definition of Britishness; this was their cri de coeur to be included in the public sphere. After the memorial’s completion, Greville Janner, a Labour MP (who spearheaded the campaign for the memorial), stated in his 1983 Presidential Address to the Board of Deputies of British Jews: “I salute the common ground which we share in this happy land. Whether that ground was literal, as in Hyde Park, on our honourable and solemn Holocaust memorial site, or metaphorical, through that democracy which we share, we salute that argumentative diversity that unites us in the service of others as of our own.”7 Ultimately, however, since British Jews were focused on inclusion, and therefore forced to adapt to the contingencies of British government policy, they failed to make an effective Holocaust memorial, that is, a memorial that creates a space for people to remember the victims of the Holocaust and for people to learn about what happened to prevent reoccurrence.

The Hyde Park Holocaust Memorial provides an example of Jewish communal leaders capitalizing on an opportunity to stake a claim for themselves as specifically “British” rather than merely a religious and ethnic minority living in Britain. As the cultural geographer Peter Jackson articulates it, “[c]ultures are ranked hierarchically in relations of dominance and subordination along a scale of ‘cultural power’. Subordinate cultures frequently appropriate material resources from one domain and transform them symbolically into another.”8 Lobbying by the Jewish community for a memorial on state land reflects the hierarchical dynamic between dominant and subordinate cultures that Jackson describes.

Opportunities for Jews to attempt such a claim arose from identity politics in 1970s and 80s Britain. While this Holocaust memorial later came to serve as a means for Britain to use its Jewish community to exhibit its “diversity” and “multiculturalism”, initially these were fraught goals for British national identity. First, we need to establish the identity politics at play: what exactly did it mean to be “British” and “Jewish” at this moment in British history comparatively soon after the transition from Empire to Commonwealth? The demographic restructuring brought by the influx of immigrants from the Commonwealth amplified questions about Britishness and who belonged.9 Thatcher gave an infamous television interview in 1978 when she empathetically addressed people who “Are really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture.”10 Thatcher was essentially defining anyone who was not culturally “British” as an “other”. Linda Colley offers a useful frame to understand the constant conflict between Britishness and a true acceptance of all the constituents of a diverse population. She has argued that British national identity is defined through a set of values that stand in opposition to an established “other”. Frequently this dissonance around Britishness and identity comes from a fear of the “other” incorporating itself into one’s own identity.11 Thatcher’s statement offers a stark view of how multiculturalism was seen at that time: not British.

Exploring the events that led to the Hyde Park Holocaust Memorial’s construction and the politics surrounding its construction reveal the debate in the 1970s and 80s of inserting Jews into definitions of Britishness. This is clear from the first proposed site for the memorial, on Richmond Terrace near the Cenotaph and the Department of Defence. The centrality of this space demonstrated the Jewish community’s desire for a prominent presence in British public space. Placement at this first proposed site would have claimed cultural space and metaphorically represented full cultural acceptance for the Jews in Britain. However, this site failed to gain approval, ultimately because an ethnic minority did not deserve a monument on Whitehall – arguably at the core of Britain’s national monuments. Kirk Savage argues that the Mall in Washington DC is the monumental core of the United States, meaning it visually imposes the power and strength of the federal state in order to create a collective history and identity. The Mall achieves this because it acts as a pilgrimage site, drawing together masses of people who believe in that national history. The monuments in Whitehall act similarly: they tell a narrative of British imperialism and strength before the two World Wars, and honour and celebrate the victories of those wars.12 Importantly, the Holocaust memorial design remained consistent between Richmond Terrace and Hyde Park, but in the context of each site its symbolism and meaning changed dramatically.

Britishness and Jewishness in the 1970s and 1980s

Britishness is a thread of nationalism that is based in a belief that there is a commonality among the people as a collective subject, the state that rules them, and the territory in which they live.13 “Britain” is a constructed space – it is not Great Britain, the United Kingdom, or the British Isles – it is, as Benedict Anderson described, some imagined amalgamation of all three united by Crown, government, and a common language.14 In “Britain”, the collective subject in question – the basis for a nationalist ideology – is dominated by the upper class. In the same 1978 interview quoted earlier, Margaret Thatcher also said: “the British character has done so much for democracy, for law, and done so much throughout the world that if there is any fear that it might be swamped people are going to react and be rather hostile to those coming in.” Later in the same interview she continued, “We are a British nation with British characteristics. Every country can take some small minorities and in many ways they add to the richness and variety of this country.”15 Evident in these words is the populism, conservatism, and negative stance towards non-native British citizens that was at the core of Thatcher’s politics. Thatcher’s words encapsulate the tensions between ethnic minorities and notions of Britishness and British nationalism. If we use Colley and Anderson to understand Britishness as the construct of an imagined collective bound by territory and government, then Thatcher indicates two tiers in the British nationalist framework. First is the British nation with British characteristics, and second are other people who may contribute socially and economically but who are not the core of the nation.

For centuries Jewish communal leaders led a constant struggle for emancipation and acceptance into mainstream British society. Established in 1760, the Board of Deputies of British Jews (BoD) sought to represent a unified Jewish community, regardless of religious denomination or European origin, to the government, and lobbied for their interests.16 The leaders of the community believed that Britain bestowed a degree of hospitality on the Jews, allowing them to live, work, and worship freely, in return for the Jews providing gratitude and allegiance to the Crown and state. As a result of this pseudo-contract, the wealthier Jewish leaders manifested Jewish loyalty as conformity, and sought to rid themselves of as much of their “Jewishness” as possible. As David Cesarani argued, the construction of an Anglo-Jewish heritage was not intended to establish and continue Jewish values; instead it was used to challenge the notion that British Jews were not British, and amalgamate a singular British and Jewish heritage.17 They assumed this policy of conformity would rid Britain of antisemitism: if British Jews appeared just as “British” as everyone else, it would surely be a matter of time before discrimination disappeared. However, instead of becoming acculturated Britons, the leaders of the Jewish community developed an internalized antisemitism.18

This approach by the wealthier, educated Jewish enclave was successful in part because of the centralized organization of the Jewish community. The formation of a (perceived) cohesive group of British Jews followed a significant increase in immigration from Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century and subsequent anti-immigrant sentiments from inside the Jewish community towards less acculturated Jews. Jews who immigrated escaped antisemitism in Eastern Europe, and the Jews who were already living in Britain desired to avoid the trope of the alien group who did not fit into mainstream society.19

Are British Jews British?

While the BoD’s decision to lobby Thatcher’s government for a memorial symbolizes the Jewish community’s attempt to conform and acclimatize to British society, in reality the Board and other Jewish communal leaders were challenging the homogeneity of Britishness. A large part of my discussion revolves round the notion of heritage and belonging. Put differently: is the Holocaust part of Britain’s history and heritage? As David Cesarani wrote, “[h]eritage constructs a mythological national unity and homogeneity that excludes or marginalizes minorities.”20 Heritage is a construct designed to exclude the other, so the notion of assimilating and joining a specific historical legacy or cultural tradition is fraught with contradictions. This is particularly acute in the context of British Jews, forever vacillating between being considered neither Jewish enough nor British enough. Thus, the project of becoming fully British was doomed to fail from the start. Underlying these questions is another: do the Jews belong in British society? By absorbing the Jewish community into the construct of “Britishness”, the Hyde Park Holocaust Memorial was and still is an attempt to fracture the status quo.

In Britain Jews were not considered British enough, but to Jews in Israel or the United States, British Jewry was not Jewish enough. British Jewry’s petition for a Holocaust memorial in 1979 stemmed from pressure exerted by Jews from all over the world to bring the horrors of the Holocaust to the forefront of public consciousness. At the 1979 Claims Conference for Victims of Nazism in Geneva, the prominent Israeli Holocaust historian Yehuda Bauer criticized British Jewry for not having done enough to memorialize publicly the Holocaust. The BoD and its subcommittee, the UK Yad Vashem Committee (UKYVC), took offence at the remarks.21 They claimed that British Jewry had in fact taken action to promote the history and legacy of the Holocaust and its victims.22 Yet, even a brief examination proves that the activities by the BoD and UKYVC were limited, with only minimal education of the population about the Holocaust, and scarce memorialization of its victims. Before 1979, the BoD established Holocaust memorial committees, raised money for a professorship and post-doctoral fellow at Oxford University for Holocaust studies, and funded the publication of books (such as Martin Gilbert’s The Atlas of the Holocaust, 1982) as resources for school children to learn about the Holocaust in their history lessons.23 In the 1960s the Warsaw Ghetto Memorial Committee was established within the BoD. Its foundational goal was “to promote activities to lessen racial tension, condemn racial discrimination, and to work with others doing likewise and to establish a permanent memorial to the heroes of the Warsaw Ghetto uprising; as well as the six million Jewish and millions of other victims of Nazism.”24 The Warsaw Ghetto committee developed ideas for exhibitions and memorials, but nothing of note ever came to fruition. Further, as stated in their goals, any memorial they would have built would not have been a memorial for the sake of remembering Holocaust victims, but a memorial to “lessen racial tensions”. In essence, it was a memorial to help assimilate British Jews.

It is true that compared to other centres of postwar Jewry, such as the United States, Israel, Australia, and Canada, Britain had done the least in terms of Holocaust commemoration by the end of the 1970s. Arguably, this is because British Jewry was focused on Jewish integration within British society, and therefore did not deliberately promote their narrative as exceptional. Bauer’s critique of British Jewry called into question the priorities of British Jewry. The 1979 meeting had a ripple effect; soon afterwards, Greville Janner was elected President of the BoD and within a few months met Heseltine about a memorial, decisively shifting the BoD’s Holocaust commemorative programmes into the public sphere.

Why build a memorial? Nationalism and public recognition

Similarly to nationalism, identity is another term used to group individuals who share a perceived sense of unity through place and time. Memorials are a way to concretize that identity. People also build memorials to make sense of the world’s complexity and perform “memory work” as a collective, and in order to continue to construct an evolving sense of identity. Memory, as famously defined by Maurice Halbwachs, shapes our collective understanding of the past both individually and societally.25 National memory and identity are a set of ideas and beliefs shared by vast numbers of people who have no real connection to each other apart from geography and time. Yet, national identity is a notion heavily controlled and guarded by the people who purport to regulate it: governments and male elites. Governments build memorials (as opposed to plaques, days, books, and so on) to highlight certain moments in their nation’s history and to craft a national image. State-sponsored monuments typically affirm a nation’s glorious pasts, validate its triumphs, and honour those who died for the good of the nation. Granted, memorials are contingent on their audience, culture, and society, who often determine their own meanings and symbolisms despite planners’ intentions. However, Kirk Savage writes, “If the nation is ordinarily experienced in a diffuse, ever-shifting circulation of words and images, national monuments acquire authority by affixing certain words and images to particular places meant to be distinctive and permanent.”26 We build memorials in the hope of making a national sentiment everlasting through sculpture and architecture.

In Britain, one important memorial that falls into this category is the Cenotaph. Designed in 1919 by Edwin Lutyens, it is a straightforward 35-foot stone pylon with a series of steps, culminating in an empty sarcophagus at its apex. Carved laurel wreaths commemorate British soldiers lost fighting for their country. The memorial’s sombre, yet unemotional, form allowed all British citizens a space to mourn. Its modest rectangular form offers an egalitarian memorial space for people from all social classes collectively to remember the fallen soldiers. There are no symbols of king or country on it, and Lutyens carefully avoided overt representations of politics and military grief, which resulted in its appeal throughout the country.27 Absent is any jarring wartime, figurative imagery. It lacks victory symbols, such as a column or a Greek mythological figure. The subtle planarity and minimal sculptural qualities of the Cenotaph are precisely why it has come to represent a sacred national space in British collective memory since the world wars, and has been copied in many towns and cities around Britain. British memorials, particularly war ones, became central to postwar British identity, commemorating those who died during the world wars as true patriots and people of honour.

Why build a Holocaust memorial? Locating Jewish identity within national identity

In this context, British Jews set their sights on their own memorial, binding their legacy and contribution to Britain. But what does a Holocaust memorial have to do with national identity? For Jews themselves, a Holocaust memorial unites the Jewish community under a shared trauma. It physically serves as a centralized space for personal memory work and mourning. A Holocaust memorial also connects Jews with other Jews who are geographically far apart. It was implicit in Bauer’s critique of British Jewry that they needed to build a Holocaust memorial to demonstrate their loyalty to world Jewry. After thousands of years of persecution, the Holocaust now serves as the focal point for Jewish suffering and identity. Frequently, Holocaust memorials will have allusions to those countries where Jews died or where they emigrated from, creating a physical demonstration of the global scale of the Holocaust.

My understanding of how Holocaust memory intersects with British national memory stems from James Young’s fundamental observation that Holocaust memory is diverse and reflects the country in which it is being commemorated. Young wrote: “[f]or national memory of what I might call the Shoah varies from land to land, political regime to regime … At the heart of such a project rests the assumption that memory of the Holocaust is finally as plural as the hundreds of diverse buildings and designs by which every nation and people house remembrance.”28 Young’s categorization of Holocaust memorials and memory as “plural” refers to how various nations have come to use and adapt that memory for their own political purpose. In other words, the Holocaust becomes a symbol or paradigm for governments to craft a contemporary identity. For example, the United States used the Holocaust to champion liberty and democracy, postwar Poland created Holocaust memorials to establish firmly Polish nationals’ place as Nazi victims, and Israel built Holocaust memorials that define the founding of the State of Israel as the next chapter for Jews after the Holocaust. Young also argued that a nation’s monuments create “a matrix” that “emplots the story of ennobling events”, thus creating a constructed web of historical events that weave into a national history or memory.29 Additionally, discussing the politics of remembrance in national memorials, Kirk Savage argues that the memorialized persons become important in constructing national narratives because they offer the nation an opportunity to define itself as a people that memorializes victims (whether that be of war, genocide, terrorism, and others). Savage writes, “which victim deserves a monument is a fundamentally political question, whose answer depends on the meaning that society assigns to the trauma.”30 Thus, at a moment when Britain’s political allies were funding projects focusing on Holocaust memory and nationhood, British Jews sought to build a Holocaust memorial in Britain both to align with global Jewry and to establish acceptance and equality within their own, British, society.

A memorial that was primarily about Jewish history and personhood aiming to achieve acculturation seems like a contradiction. How can a memorial about a unique historical event that happened to the Jews integrate the British Jewish community with their United Kingdom neighbours? If this memorial was successful perhaps it would make the general British population aware of Jewish history and plight, and would potentially ensure some level of protection if something like the Holocaust happened again? The Jewish leaders led by Janner believed that if this equation could succeed then the Jews would really be a part of the nation, protected and respected by their fellow countrymen and women.

In other countries Holocaust memorials were used to construct this relationship between the local Jewish communities and the state. For example, in the United States, Jews of the Democratic political party saw an opportunity to push a Holocaust memorial project onto the president’s agenda when Jimmy Carter’s government sold aircraft originally earmarked for Israel to Egypt and Saudi Arabia in 1977. Additionally, as documented extensively by Edward Linenthal in his monograph about the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the powerful Democrat Jewish lobbyists were outraged by Carter’s exploration of diplomatic relations with the Palestinian Liberation Organization. Thatcher’s government also explored relations with the Palestinian Liberation Organization in 1980, and her agenda to develop a diplomatic relationship with them was probably a factor in her support for the memorial as an appeasement to her Jewish constituents.31 In 1978 Carter enacted the President’s Commission on the Holocaust and in 1979 the Commission recommended the construction of a national Holocaust memorial museum.

The example of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) clearly demonstrates how the Jewish community capitalized on a political moment to further their own memory and place within American society. The government’s response to that reflects its use of Holocaust memory and history to symbolize the paradigm of American democratic values. In his speech announcing the plans for the museum, Carter said, “[t]o memorialize the victims of the Holocaust, we must harness the outrage of our own memories to stamp out oppression wherever it exists. We must understand that human rights and human dignity are indivisible.”32 Carter emphasized the need to remember the victims, and to create a place to work through society’s collective anger about the destruction. He publicly stated that his objectives for founding a permanent Holocaust memorial in the United States were to educate the public, help the country understand the history, and position the Holocaust as antithetical to the US’s foundational beliefs, thereby cementing a connection between the American Democratic experiment with its Jewish constituents. Importantly, even though the USHMM originated from a moment of political self-interest, that was not the primary reason why American Jews wanted a memorial. The Jewish community and President Carter worked together to establish an educational memorial to benefit the general public, symbolically using Holocaust memory and its history to bring positive changes to society.33 This is an important point of comparison with the British memorial, where Janner and the BoD were not seeking a memorial to help other minority groups integrate, or to benefit the public in any way. It entirely stemmed from the institution’s self-interest.

Making the Memorial and Jewish entry into Britishness

It was Janner who privately spoke to Heseltine to request that the government fund the memorial. That this memorial started in private is significant. Janner keenly understood the political climate. It does not seem accidental that memorial discussions began in private, and that Janner chose which arguments would be most likely to work in his favour. Firstly, as mentioned, he situated his request in the context of the United States’ actions surrounding Holocaust commemoration, reminding Heseltine (and by extension Thatcher) about the political gains to be made through a Holocaust memorial. Secondly, Janner highlighted that the memorial would be about commemorating the eleven million victims of the Nazis, and emphasized that the Jews were just a part of that whole.

The focus on this eleven million, which includes Jews and non-Jews, versus the six million Jewish victims of the Holocaust, signals that the Jewish community was not looking for a way to be regarded as exceptional or to highlight their trauma as different, but sought to do so in a way that acknowledged their integration into a larger community of victims and of members of the British tradition. In my previous discussion of when Bauer criticized British Jewry for their lack of public Holocaust commemoration, I posited that a reason for the historic passivity of British Jews was their assimilationist agenda. For centuries British Jews fought hard to establish their integration into British society. Having a Holocaust museum or large monument would instead allow British nationals to learn about the exceptionalism of the Jewish experience and the distinct form of racism that is antisemitism. By comparison, during the planning phases of USHMM, led by Elie Wiesel, the instigators demanded that the core of the project be about the Jews murdered by the Nazis. They emphasized the singular, exceptional Jewish experience in the Holocaust while also acknowledging the other victims of the Nazi genocide.34 Wiesel’s stance contrasts greatly with Janner’s position. From the correspondence between Janner and Heseltine about the London memorial, it is clear that the Jewish community wanted the memorial to be open and accessible to as much of the British population as possible, and thus the Jewish focus was marginalized from the outset. Janner and Heseltine first discussed the memorial around 15 July 1979, about four months before they announced it. In a letter thanking Heseltine for the meeting, Janner wrote: “This would be intended as a tribute, a reminder and as a memorial to some eleven million murdered people, of whom perhaps six million were Jews and five million non-Jews. It would also recognize that we are indeed fortunate not to have been among the victims.”35

Richmond Terrace: the original site

The announcement of the memorial foregrounded reluctance regarding the construction of a memorial to supposedly non-British subjects on public land. It was originally intended for Whitehall, specifically on Richmond Terrace in front of the Ministry of Defence. That location was chosen because construction was already scheduled to begin on Richmond Terrace and the architect’s plans for the building included space for a monument. The site is fairly close to the Cenotaph, which as discussed is an incredibly significant British memorial.

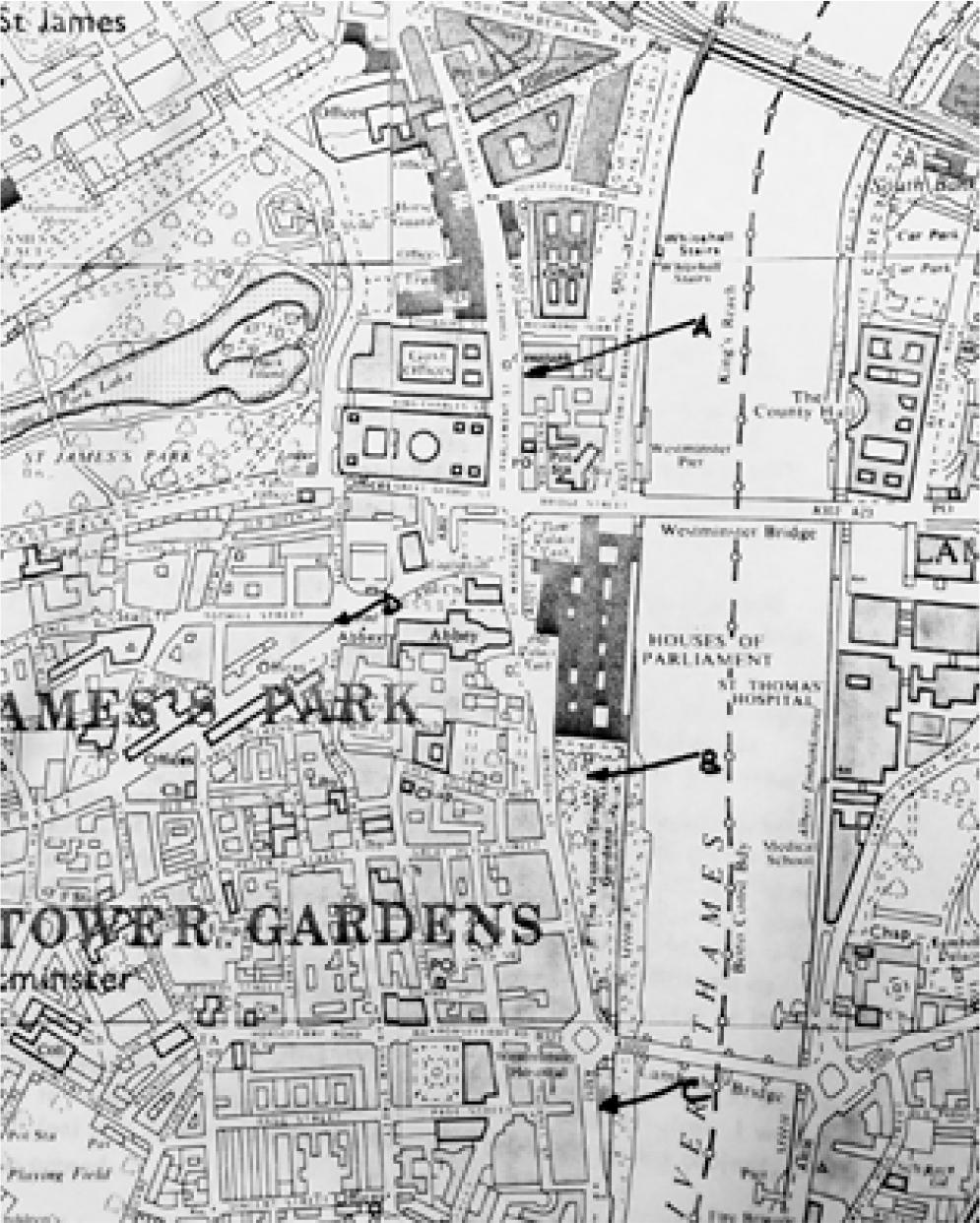

Initially, Heseltine’s team in the Department of the Environment offered Janner and the Jewish community a series of high-profile spaces, all of which would have given a Holocaust memorial a sense of gravitas by locating it near important national and historic buildings. However, the government rejected all of them. Their reasons suggest a fear that a Jewish memorial does not actually belong on public land for all to see. As seen on a map from the Department of the Environment’s archives, the alternative spaces included an option in Victoria Tower Gardens, where restoration was scheduled for a Rodin sculpture; another near Parliament Square and Westminster Abbey; and the last option was by Lambeth Bridge, along the riverfront. The chief architect for the Department of the Environment was concerned with vandalism and antisemitic attacks on a memorial if it was in the park or along the waterfront, leaving it vulnerable at night.36 Heseltine was hesitant about the Victoria Tower Gardens location because of its proximity to the Houses of Parliament and because MPs often gave television interviews from this location. He feared a Holocaust memorial in the shadows of the Houses of Parliament would be a disturbing juxtaposition for those occasions. This out-of-sight, out-of-mind attitude expressed by Heseltine reflects the late imperial British approach to emotion and uncomfortable topics, raising further questions about the place for a memorial to one of the most gruesome events in history. Heseltine’s reasons and attitude when rejecting the park and waterfront sites reveals that – even before the general public or the rest of the Cabinet were brought in – the Department of the Environment felt that the Jews were not in fact “British” enough, nor was the Holocaust part of British history.

Map showing optional locations for the proposed memorial, 1979–80. The National Archives, FCO 33/4845

Key: The lettering and arrows point to options given by the government to Greville Janner for the memorial: A: Richmond Terrace; B: The east end of Victoria Tower Gardens (directly west of the Houses of Parliament); C: The west end of Victoria Tower Gardens (directly west of Lambeth Bridge); D: A triangle of land in front of Westminster Abbey

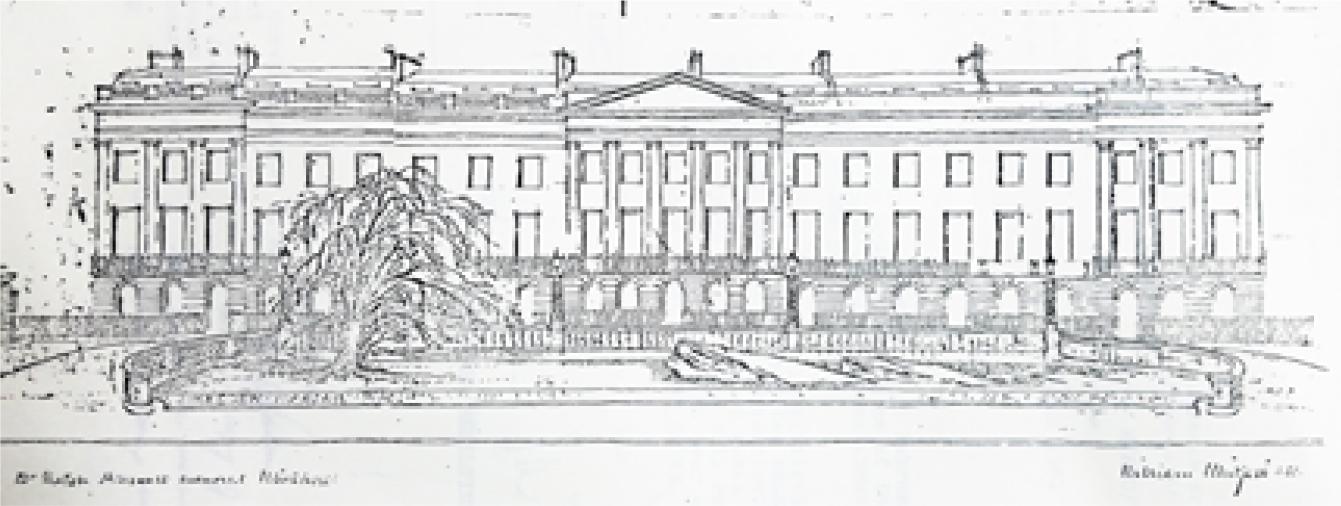

Richmond Terrace was the most suitable option because it was undergoing a complete rebuilding, designed by William Whitfield (1920–2019) and completed in 1987. The site originally housed one of the grandest homes in London, Richmond House, designed by Lord Burlington, the second Duke of Richmond, in 1720. In the nineteenth century the house was converted into terraced houses, rented by private individuals, and became known as Richmond Terrace. In the early twentieth century, the government took over the property, and it held various offices over the years. By the time Whitfield came to renovate it, the buildings had fallen into disrepair, and it was considered a waste of prime government office space.37 Whitfield’s plan for the building was to have a Brutalist front, incorporating a brick and concrete façade to serve as a backdrop for the Cenotaph. The Brutalist front was to provide a stage for the angular aesthetic of Lutyens’s design. Undulations in the façade also ensure that every office inside had natural light. The side of the building off Whitehall, facing Scotland Yard and the Ministry of Defence, incorporates classical elements with brick and concrete to recall the historic classical architecture of the original Richmond House.38 Heseltine intended to place the Holocaust memorial along the classically inspired side of the building.

The Richmond Terrace site appeared to meet all the needs of the Jewish community and the government. It was in a well-secured, available plot of land that the Department of the Environment allocated for public sculpture, and, for the Jews, the prime piece of real estate allowed Jewish memory to stake a claim physically within British national memory. However, the notion of Jewish memory and heritage sharing space with British national heritage in such a public way did not sit well with many of Thatcher’s ministers. There were two primary concerns with the Whitehall site. First, its juxtaposition with the Cenotaph caused offence. Since the Cenotaph memorialized all victims of the First and Second World Wars, Pym argued that Holocaust victims were already included in the Cenotaph’s purview, and the Holocaust memorial’s nearby placement would lessen the contribution of the British and Commonwealth soldiers who died fighting for their country.39 While Pym may have thought the Holocaust worthy of a memorial, he made it clear that it did not belong in a British public space. Taking a more extreme approach, Lord Carrington (then the Foreign Secretary) questioned whether or not a Holocaust memorial should exist at all. He said at a Cabinet meeting in November 1981: “the Holocaust Memorial should not be sited on Crown property. The Memorial has nothing to do with Britain. … [It would be preferable for the] Board of Deputies to buy or lease their own site in London, and either erect a Memorial privately or preferably create something useful like a park or playing field.”40 This Cabinet meeting makes evident that the government ministers still held to historic definitions of what and who was “British”, and victims of the Holocaust or their coreligionists did not fit into that definition.

The Memorial's original design

It is not known whether Carrington and Pym’s objections directly impacted the memorial’s design. There are no discussions in the Board of Deputies archives that indicate whether Janner and his team made concessions to appease the naysayers; there is not even discussion about constructing a simple, inoffensive memorial if that was all that was obtainable. The absence of such discussion implies that from the outset the Jewish community was not interested in making a statement about Jewish exceptionalism and trauma. Rather, they simply wanted to be included in the national landscape. This analysis of the original design was pieced together from one primary drawing and a series of memoranda circulated among the people involved. The design is anonymous, which speaks to the memorial project as a whole and its ultimate failure as a successful memorial. This unsigned drawing shows the memorial in front of a sketch of Whitfield’s plans for Richmond Terrace. Its classical elements are emphasized, showing a tripartite façade, a fictive portico – complete with engaged columns and a pediment – and a fence wrapping round the front of the building articulating a curved driveway or walkway. That fence has a scroll motif going round the area of the memorial, serving as a pseudo-frame and tapering off at street level, where a curb separates the area from the pavement. The memorial consists of a grassy bed with a willow tree and large jagged boulders placed to look as if they were organically emerging from the earth. Inscribed on the left side of the kerb is “Dresden Warsaw Hiroshima”.

Considering this memorial’s urban context, its use of natural rocks and trees emerging from the ground without apparent order or symmetry would have been in sharp contrast with the classical architecture of the adjacent government buildings. Furthermore, the other monuments along Whitehall are traditional early twentieth-century Beaux-Arts figurative memorials with a figure on a horse or standing in contrapposto atop traditional pedestals. The rocks in the Holocaust memorial drawing suggest an untamed landscape or heath, breaking the manicured and controlled nature of Whitehall. However, it contains no real allusions or references to the Holocaust.

Fred Kormis’s proposal for a Holocaust memorial in London, c. 1980. London, The Wiener Holocaust Library, Fred Kormis Papers 1032/2/243

This version of the memorial offers a temperate, British response to a historical event that is anything but that. Even within the Jewish community, individuals spoke to Janner about creating a memorial with a greater impact. Among those complaining was Fred Kormis (1897–1986), a moderately successful London-based Jewish sculptor and survivor of multiple concentration camps as a British prisoner of war. In 1982 he proposed a design consisting of two cast bronze arms rising from the ground, reaching up in prayer towards heaven. Janner replied to Kormis that the memorial would not include figuration of any kind.41 Information about the memorial’s design is limited, and why figuration was ruled out from the beginning is unclear, but it aligns with the rest of the discussions about the memorial from the Jewish community’s perspective. They wanted to create a memorial that would be accepted by all, one that would not offend anyone with disturbing imagery or content related to the Holocaust. This resistance to distressing imagery was first expressed by Heseltine when he rejected a site next to the Houses of Parliament. I contend that the opposition to figuration aligns with the tone Janner had in his original discussions with Heseltine about the memorial, and served to further Janner’s plan of avoiding Jewish exceptionalism and promoting integration. In that correspondence, Janner made it clear that the memorial would not be a strictly Jewish one and that it would be a memorial to all the victims of Nazis. From the outset Janner established that the Jews were not going to advocate for their voices to be raised above those of other groups. The goal of the memorial was to blend in with British society, integrate, and continue a strategy of acculturation that had been ongoing for generations.

The memorial ultimately suffers from the compromise not only that the Jewish community should not stand out but also from a view that the aesthetics should be the same for a memorial for a Jewish cause as a memorial for a solely British one. In the correspondence and meeting notes, there are suggestions of alternative designs or added elements to the memorial garden.42 However, no archival drawings exist. In memoranda between Thatcher and Heseltine’s offices, they discussed the idea of having an eternal flame as part of the memorial. Thatcher rejected this idea outright: “I concede that the project in its revised form is now open to much less objection, provided (a) there is no question of the eternal flame, which would surely be quite inappropriate when there is no flame at the Cenotaph, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier or War Memorials generally in this country”.43 Arguably, a composition comprised of rocks and trees appeared to be the least objectionable path towards getting the memorial built, but again, any overt, specifically Jewish symbols were omitted from the memorial.

The drawing that we do have lists three cities, Hiroshima, Dresden, and Warsaw, offering content related to the Second World War. At first glance, one might assume that this is important content for the memorial. However, the commonality linking those three cities is that they were demolished by Allied forces’ bombings. The British firebombed Dresden; Warsaw (at that point in history) was the epicentre of Holocaust history and memory culture; and Hiroshima’s decimation by the Americans’ atomic bomb made it the ultimate symbol of modern warfare. This reading of the memorial in conjunction with its site adjacent to the Cenotaph and the Ministry of Defence depicts the Holocaust as a summation of a new type of violence in the twentieth century.44 Rather than a project of mournful memorial focusing on victims, this design could be read as self-reflective. It seems to consider Britain’s role in the war and to offer a new lens for the Cenotaph’s straightforward approach to mourning the dead.

It comes as no surprise that the government took issue with these three cities. Pym wrote to Heseltine and Thatcher:

Indeed I am afraid that I am still not entirely clear what is the object of the proposed memorial. I had understood initially that it was to commemorate the victims of the Nazi Holocaust; but in the sketch which you showed me only three words legible along the front of the monument are Dresden, Warsaw, and Hiroshima. It is a legitimate subject for debate whether the monument should refer by implication to the victims of Allied bombing, but it is one which certainly needs to be discussed.45

Pym’s confusion regarding the design reflects the obvious problems with the memorial. The design is not about the Holocaust in any apparent way. Even my possible analysis of the significance of these cities’ names would require a lot of reflection, meditation, and knowledge to discern any meaningful content about the memorial. However, in Pym’s letter he offered an alternative memorial for the site:

The memorial to the victims of the Holocaust is of course not the only one about which we have to think at present; there is also the prospective memorial to Lord Mountbatten. As I reflect upon this, I am increasingly attracted to the thought that a statue of Lord Mountbatten outside Richmond Terrace would both fit in admirably with the other memorials in the neighbourhood and commemorate his own association with Richmond Terrace when he was Chief of Combined Operations in wartime. I should like to urge you to consider carefully whether this might not be the most appropriate solution for Richmond Terrace.46

Pym countered a potentially self-reflective memorial – one that might even deign to impugn British history – by making clear that the memorial does not belong at all on land that is drenched in British wartime history. Instead, he offered the antithesis, championing someone whom he called a wartime hero: Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy in British India. Pym’s argument for Mountbatten, a colonial leader and the embodiment of the English upper class, exemplifies traditional notions of Britishness. In Pym’s mind, this glorious Anglocentric past still comprised the core of Britain’s national legacy.

Pym was not alone in his desire to put forth a more traditional “English” subject for the site. Carrington agreed, stating that Crown Land should not be used for “a foreign memorial.”47 Thatcher’s personal notes from the November 1981 Cabinet meeting read, “the Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary said that, in his view, the Holocaust Memorial should not be situated on Crown property. The Memorial had nothing to do with Britain.”48 Carrington did concede it was probably too late and that the government should offer the Jews a more low-profile site where it would be less of a disturbance. It appeared that the Richmond Terrace site was too central to historic British memory and including a memorial to an ethnic minority was not conducive to that space. Thatcher seemed insistent that the government hold up its agreement with the Jewish community and provide a suitable piece of government land, so the discussions then turned to the Royal Parks.

The second site

Shifting the Holocaust memorial to the Royal Parks both physically and symbolically negated the memorial’s prominence. It showed that the history and heritage of the Jews did not belong alongside that of the British. The Royal Parks are still public land but are less obviously political and a less conspicuous site than Whitehall; therefore, they were seen as a suitable compromise to uphold the government’s commitment to the memorial while still being able to hide it within a park. The government also decided that the memorial would be a simple garden of remembrance, again limiting the project not only in terms of site but also of content. These series of compromises make clear that the primary goal from the government’s perspective was to placate the Jewish community, while also barring them from true inclusion into British national memory. Recognizing victims of the Holocaust and constructing a meaningful memorial space was incidental at best and at worst a begrudging concession.

There was some discussion about which royal park should be used. St. James’s Park was offered but quickly ruled out because it had no history of memorials and monuments. Its proximity to Buckingham Palace was considered problematic, demonstrating again how an association between the Crown and a “non-British” issue was unacceptable to the government.49 Green Park, which houses many sculptural memorials, was discussed as a reasonable option, but Heseltine suggested that it was not the best idea because the area was “crowded and heavily trafficked.”50 We see the continued desire to hide the memorial and put it in a place where fewer people would see it. At one point Carrington even suggested siting the memorial in the Docklands, specifically where Canary Wharf stands now, an area developed during Thatcher’s tenure as Prime Minister. At the time of these discussions, getting to the Docklands would have been difficult, with no public transport links, and placing the memorial deep in an industrial area would have been tantamount to it not existing at all. Janner rejected this idea immediately, giving as his reason that most of the Jewish community no longer lived in East London, “so that such a memorial would be dead rather than alive.”51 Overall, the Government ministers sought to move the memorial as far away from the heart of London as possible.

Ultimately the Government, led by Heseltine in the Department for the Environment, decided that Hyde Park would be the solution to all the various concerns: it was the only Royal Park patrolled by the London Metropolitan Police, which it was hoped would ward off vandalism. Furthermore, Hyde Park was the largest park in London, so the memorial could be inconspicuous and thereby potentially avoid controversy.52 The safety and security concerns Heseltine gave to Janner were ultimately inconsistent because they chose a dell for the memorial. A dell is a small, secluded valley often in a larger park that is designed to evoke a natural, wooded space. There are many prominent and open spaces in Hyde Park, which is a large tract of land in the centre of London. Placing the memorial in an isolated, tree-covered space would in fact be a prime space for vandals and antisemites to deface it, since it would be hard for any passersby to see. Claiming that a dell in Hyde Park is a safer space than Whitehall, which is adjacent to Scotland Yard and the Ministry of Defence, is illogical. This questionable rationale makes clear that the issues of vandalism and high public traffic were excuses to move the memorial into the shadows of some trees where Britain could publicly claim to the world that they do have a Holocaust memorial and stand in strong opposition to fascism while not addressing any of the difficult subject matter underlying a Holocaust memorial. It simultaneously makes evident that Thatcher’s government neither recognized the suffering of the Holocaust as relevant to its own history, nor saw the Jewish community as truly acculturated and British.

Ultimate construction of the Hyde Park Holocaust Memorial

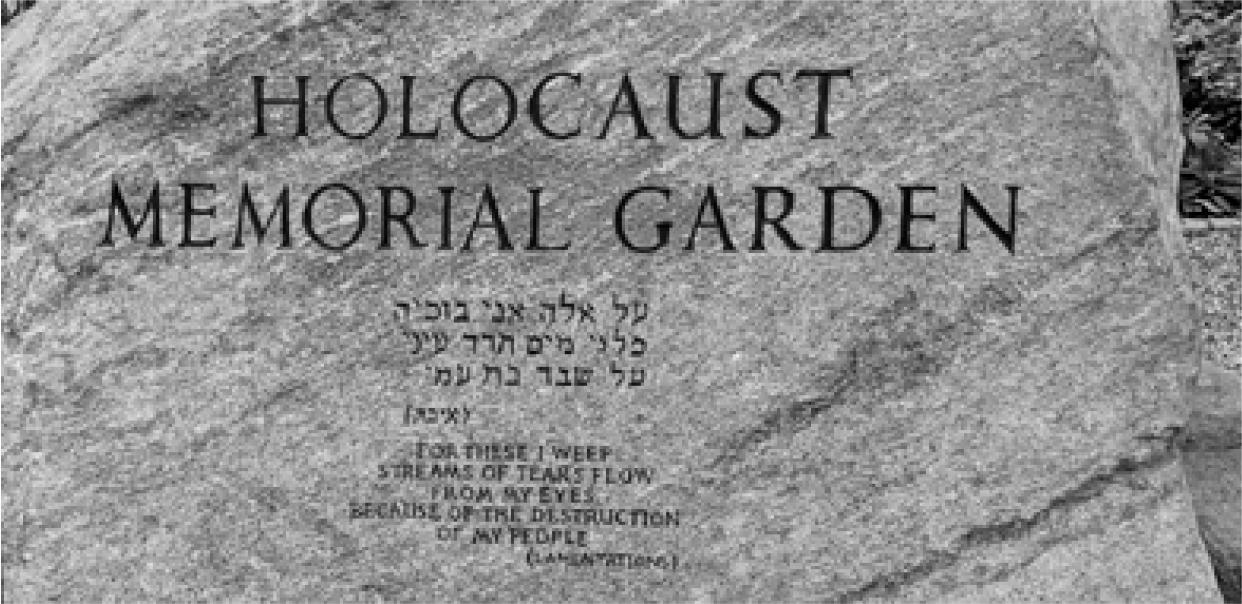

The memorial that was built achieved none of the goals it set out to do: it neither raised awareness about the Holocaust for the average British citizen, nor did it provide the Jewish community with a place to mourn and gather over their shared trauma. It was ultimately built in the Dell in Hyde Park and designed by the architect Richard Seifert (1910–2001). The BoD paid for the materials and the architect, but the government donated the land. Seifert’s memorial blends in so well with the dense landscaping of trees, bushes, and other rocks that even if one actively seeks it out, it is easy to miss. The final design consists of two large boulders in a gravel bed surrounded by trees and greenery. One of the boulders reads in capital letters “HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL GARDEN”. It is also inscribed in Hebrew and in smaller capitals with a verse from Lamentations (1:16), “FOR THESE I WEEP/STREAMS OF TEARS FLOW/FROM MY EYES/BECAUSE OF THE DESTRUCTION/OF MY PEOPLE”.53 There is no mention of Jews, Nazis, or when the Holocaust occurred. Based on the information present, an ignorant visitor might even surmise that the Holocaust was a biblical event.

In addition to the large boulders, smaller stones in a gravel bed surround the larger rocks, and silver birch trees line the circumference of the space. Although the memorial is secluded and lacks any content specific to the Holocaust, the landscaping is cultivated and not heath-like, which makes it clear to anyone who notices the garden that this is different from the immediately surrounding areas. The garden’s gravel bed is lined by rectangular stones, distinguishing the ground of the memorial from the rest of Hyde Park, marking a clear boundary. The memorial does not entirely get lost among the trees if one is looking closely. It is possible to discern the transition from grass to gravel in a park otherwise dedicated to lounging and recreation, a subtle boundary that creates a physical distinction that encourages contemplation and elevates the memorial’s significance. One can also hear the fountains and running water from the Serpentine, and because the memorial is in a dell, there is an odd quietness that one rarely finds in a city like London. All in all, the site itself could have been used to create a beautiful and contemplative memorial. But, a pleasant garden with no bench to sit on, with no symbolic designs and no historical context all but guarantees that this memorial is of no practical use to anyone. Yet, there are moments when the memorial starts to work, such as the shift from grass to gravel and the boundaries it sets between the park and itself. Unfortunately, it ultimately falls short and does not extend those moments to any meaningful elements relating to the Holocaust. To passersby, and even to some extent to people who seek it out, the memorial’s purpose and context is opaque and potentially meaningless. Even if they know a great deal about the Holocaust and garden design, they would struggle to find meaning in what is in front of them. After attending the memorial’s unveiling in 1983, the prominent Jewish leader and activist June Jacobs wrote a letter to The Jewish Chronicle expressing her thoughts on the memorial: “I wonder, though, if people passing by next week, next year and next century will understand that the rock commemorates the heinous murder of six million Jews by the Nazis.”54 Apart from its actual design, it remains very much on the periphery of the public space. This memorial is thus more an academic case study to understand just how deep tensions in postimperial Britain were between the British state and ethnic minorities at this moment in history; it shows that anyone who was not ethnically British was still seen as an ethnic other.

The memorial was unveiled on 23 June 1983, and speeches at the ceremony provide more evidence that this memorial is a story about an ethnic minority’s desire to acculturate into British society, a minority defined by the government as existing on the margins. At the opening ceremony, Heseltine’s successor as Secretary of the Environment, Patrick Jenkin, said:

There was, I know, much discussion about the site and form for a British memorial to Holocaust victims. As beautiful gardens and pleasant green spaces in large cities are features of the British environment of which we can be justly proud, I think the final decision to create a Garden of Remembrance could hardly be bettered. And Hyde Park, as the place where people of all colours, creeds and nationalities can air their views in public – that was an anathema to the perpetrators of the Holocaust – strikes me as an imaginative site.55

He added that the memorial was meant to “commemorate the victims of all faiths”,56 removing Jewish specificity from the memorial at a ceremony organized by the BoD. Jenkin’s declaration that Hyde Park is a multicultural space for all peoples is an excuse for not needing a memorial devoted to issues of racism and antisemitism. It is as if he were stating this is not an issue in Britain because we have public parks that were built to democratize public space. Similarly, the implication that hiding a memorial in a grouping of trees is meant to “protect” it demonstrates that Thatcher’s ministers were unable to reconcile their biases. Furthermore, Jenkin’s contextualization of the memorial within Hyde Park’s history as a site of protest oversimplifies the issues that a Holocaust memorial should raise. Rather than memorialize and remember the millions of humans who were murdered because of their race, religious belief, sexuality, or political views, the memorial’s goal – according to Jenkin – is to beautify the city and contribute to London’s green spaces. Jenkin’s words affirm that the government’s intentions were to build a Holocaust memorial on public land but not to integrate the Holocaust into Britain’s national consciousness.

It is important to record that on the whole Jews failed to challenge the government or critique the memorial’s obvious failings.57 Janner echoed Jenkin’s sentiment in his speech: “The garden looked beautiful and tranquil with the memorial stone itself beautifully set into its natural surroundings.”58 Even in his speech at a ceremony organized by the BoD, Janner negated any mention of Jews and the particularity of the Jewish experience during the Holocaust. This demonstrates that Janner and the BoD’s motives were not about highlighting Jewish specificity to ensure future Holocausts would never happen. It falls in line with the historian Steven Cooke’s argument that the goals of British Jews were at odds with the tendency in world Jewry to push for a narrative of Jewish exceptionalism in the Holocaust. Cooke wrote: “[t]his proved problematic for the main actors within the campaign for the monument, all leading Anglo-Jews, who were operating within a strategic framework of assimilation and non-particularity.”59 Cooke contended that the opening ceremony speeches proved that Janner’s intention was assimilation and acceptance, not building a Holocaust memorial to educate the British populace to remember what happened to the Jews during the Second World War.

By any definition of what a memorial should do, the Hyde Park Holocaust Memorial is not successful since it does not commemorate the Holocaust. After its opening, it was twice vandalized, and after only a handful of years of use the memorial was abandoned by the BoD as the site for their annual Holocaust Remembrance Day service.60 While its failure could be blamed on the site and design (which do contribute to its failings), more important was the Jewish community’s goal of acculturation over recognition of a specifically Jewish tragedy. Rather than building a space where survivors could mourn their loved ones, or constructing a site where British Jews could find a space that unified their past with their present, the memorial represents compromise and capitulation to the point of near erasure. This project initiated and driven by the Jewish community ultimately failed as a site of Holocaust memory and in its attempt to integrate British Jews within Britain’s national monuments.