Introduction

The last decades have seen a proliferation of calls for historical justice, that is, the desire to right past wrongs, in both post-conflict societies and more established democracies (Neumann and Thompson, 2015). In Sweden, such calls have led to reconciliatory investigations of abuse and human rights violations towards the Swedish Romani minority in the past and present. These investigations resulted in state-sponsored knowledge production through White Papers and teaching materials for schools (Government Offices, 2010, 2011, 2015). In this new era of reconciliation, indigenous history was established as new statutory content in secondary school history education, and the syllabus stated that students now ought to obtain ‘knowledge about the cultures, languages, religion and history of the national minorities (Jews, Roma, indigenous Samis, Sweden Finns and Tornedalians)’ (Skolverket, 2011: 11). In addition, the Swedish National Agency of Education (NAE) directed further attention to the difficult histories of the Romani by prompting secondary school students to consider the past and present of the Swedish Roma in a high-stakes national test in history in 2014. This fact accentuates that the knowledge of this – in part untold1 – past may be regarded as powerful and important knowledge in schooling. In light of the desire to right past wrongs regarding Swedish Roma history, research has called for a stronger focus on state redress in education (Fagerheim Kalsås, 2018). As scholars have highlighted history education as an important arena for social memory processes (see, for example, Ahonen, 2012; Thorp, 2016; Fagerheim Kalsås, 2021; Arvidsson and Elmersjö, 2021), this study will shed light on state redress politics in education by looking into students’ responses to an assessment task within the high-stakes national history test from 2014. More precisely, it examines how students make sense of the past, present and future of Romani peoples, as well as their human rights. The inquiry is guided by the following questions:

How do the adolescents view the intercultural idea of a shared responsibility for human rights of the Roma: who do they consider to be agents of change in the past, present and future of the Romani peoples?

How may we understand the students’ narratives of this particular past, present and future, in relation to notions of historical justice and transformative change?

In order to address the two research questions, this article comprises the following sections: a combined literature review and conceptual framework addressing the complexities of teaching difficult pasts and change; a description of the setting and context of Swedish history education; issues of data and methodology; a report of the findings; and a concluding discussion.

Realising Roma rights in a high-stakes history test: Towards a conceptual framework

This inquiry is informed by research concerning the complexities of teaching and learning about the history of minorities through a lens of recognition and reconciliation, as well as the complexities of teaching and learning about historical change for social change in the present and future. This section offers an overview of research that addresses these two notions. The section also considers the theoretical and empirical implications of this study.

The complexity of teaching and learning difficult histories through recognition and reconciliation

There is an extensive body of research concerning difficult histories, often concerning challenges, possibilities and limitations for transitional justice in post-conflict and settler-colonial societies in policy (for example, Bentrovato, 2017; Tibbitts and Weldon, 2017; Keynes, 2019; Miles, 2021); postcolonial perspectives and difficult histories in textbooks (for example, Nieuwenhuyse and Valentim, 2018; Fru and Wassermann, 2017); teacher perspectives on difficult histories (for example, Zembylas, 2017; Zembylas and Loukaidis, 2021); and students’ thinking about indigenous peoples’ history in settler colonies (for example, Sheehan et al., 2018; Miles, 2019). Research on transitional justice processes in established democracies has also been carried out, albeit with a strong focus on colonial pasts in settler colonies and the role of history education in these societies (see, for example, Winter, 2014).

In light of this perceived missing dimension, scholars have called for a stronger focus on the role of schools in state redress politics and historical reparations in Scandinavia (Fagerheim Kalsås, 2018). With regard to this call, historian Jan Löfström (2011) argues that the practical implications of these institutional apologies for history education are twofold. On the one hand, an apology may serve the purpose of providing a platform for the perpetrators and victims to share their experiences of the past in order to be better prepared for a future together. On the other hand, a historical reparations approach to the past may result in the exact opposite to its intention, and may exclude and:

… conflate the idea of political and cultural community so that ‘our nation’ as a political community [in the present] becomes equivalent of ‘our nation’ as a historically established cultural community, whereby also the notion of citizenship is given an ethnic twist: cultural belonging is made the core of citizenship. (Löfström, 2011: 104)

When an apology is given by a state in the name of the nation’s past, each individual has to decide whether s/he identifies (both culturally and historically) with the group who apologises or with the group who is being apologised to (Löfström, 2011). Thus, individuals who transcend these boundaries and identify as Swedish Roma may find themselves in a ‘cultural-political limbo’, where they are incapable of entering the national community of memory or feel obligated to abandon their collective memories of a minority past in order to assimilate (Löfström, 2011: 105). Bearing in mind how history is a narrational practice, always contingent on cultural context (Rüsen, 1996; VanSledright, 1997; Thorp, 2016; Grever and Adriaansen, 2017), research has suggested that learning about difficult pasts challenges students’ perceptions of history of cultural groups, and implicates their identities in complex ways (Elmersjö, 2015; Thorp, 2016; McCully et al., 2021). In relation to this notion, it has been suggested that such a focus on difficult pasts may have the potential to empower adolescents, further an appreciation of unity in diversity and a shared responsibility, and spark action for change in the present and future among adolescents (Ahonen, 2012; Osler, 2015; Nordgren, 2017). However, it has also been suggested that such a focus risks re-establishing stronger ethnic group identities among students, and thus impeding multiperspectivity and a sense of a shared responsibility for human rights among students (Löfström, 2011; Apple, 2014; Elmersjö, 2015; Zanazanian, 2019; for further reading on the overlapping concepts of historical culture and memory processes in education, see, for example, Thorp, 2016; Carretero et al., 2017; Assmann, 2010; Zanazanian, 2019). Thus, one may argue that the difficult history of minorities and their human rights becomes steeped as a politically charged matter of intercultural education in the present, with the potential to include and exclude people or groups (see White, 1973, 1980; Parkes, 2011, 2013).

The teaching and learning of difficult pasts through reconciliation has been noted to hold further challenges for both teachers and students (Zembylas, 2017; Chinnery, 2019). A difficult past is, by definition, ‘an ethical debt we have done nothing to incur, but which neither can we refuse’ (Chinnery, 2019: 101): a moral burden and possibility of hope, which inevitably may lead to feelings of guilt among young learners (see Seixas, 2000; Elmersjö, 2015). Difficult pasts, scholars argue, therefore call us to take a different stance on how we narrate history, and force us to acknowledge a human ‘inescapable indebtedness to [a past] which we can never fully know or understand, but for which we are responsible nevertheless’ (Chinnery, 2019: 104). In addition, the teaching and learning of difficult pasts is dependent upon space for dissent and critical engagement with narratives in the history classroom (Chinnery, 2019). Furthermore, it calls for history education to raise an awareness of historicity among adolescents in order to realise intercultural goals such as a sense of unity in diversity or a shared responsibility for the rights of minorities in the past, present and future (Chinnery, 2019; Nordgren, 2017; Thorp and Persson, 2020). However, research has noted how teaching and learning difficult histories is often met by resistance, since it challenges teachers’ own beliefs and perceptions of the past, and may cause discomfort and trigger unforeseen affectual responses among young learners as they engage with sensitive topics in the history classroom (see, for example, McCully, 2006; Zembylas and Kambani, 2012; Zembylas, 2017). Concerning sensitive historical topics, Swedish students have been noted to express distress and knee-jerk moral responses as they consider difficult indigenous pasts through assessment tasks prompting them to read and think like historians (see Nygren, 2016; Nolgård and Nygren, 2019). However, how students consider the difficult past, present situation and future of the Swedish Romani, as well as the development of their human rights in light of historical justice, remains a lacuna.

The complexity of teaching and learning about historical change for social change in the present and future

A basic premise of this study is not only that education can change society (Apple, 2013), but also that history education can be the means by which transformative social change and empowerment may be accomplished (see, for example, Barton and Levstik, 2004). Learning for change in history education is widely believed to be best enabled through transformative, active educational designs, which have the potential to empower learners to critically engage with, for example, human rights issues and work for a just world (Tibbitts and Weldon, 2017; Tibbitts et al., 2020). Scholars of human rights education and history didactics have identified this notion as ‘the change approach’, consisting of three dimensions (Tibbitts, 2002; Løkke Rasmussen, 2013). The first dimension includes that students should learn about human rights, and related institutions and their development, as well as about principles, norms and standards to obtain an understanding for the transfer of knowledge about systems upholding rights in the present. The second dimension includes learning through transformative pedagogies, supporting and enhancing solidarity, multiperspectivity, empathy and respect for human rights values. The third dimension includes teaching for change, with the aim to empower students to assert their own and others’ human rights, as well as to critically engage with human rights issues and work for a just world (see Løkke Rasmussen, 2013; Lücke, 2016; Nygren and Johnsrud, 2018). Research has been carried out regarding how these learning dimensions about, through and for change are underpinned through human rights and peace in policy and curricula (see, for example, Robinson, 2017; Parker, 2018; Standish and Nygren, 2018), and through investigations of students’ knowledge of human rights issues (see, for example, Bajaj, 2004; Kim, 2019; Brantefors, 2019; Nolgård et al., 2020; Tibbitts et al., 2020; Barton, 2020). Acknowledging the fact that there is a strong connection between education and society (Apple, 1992), learning about past historical injustices and the development of minority rights as a part of one’s own history has been brought forward as a fruitful way to further an active engagement with issues related to historical justice within and beyond borders (Osler, 2015; Struthers, 2015, 2017). Previous research within history education has, however, found indigenous peoples’ difficult pasts to be a silent historiography in history textbooks (Mattlar, 2014, 2016), as well as in students’ perceptions of the history and development of human rights (Nolgård et al., 2020). Swedish adolescents, specifically, have been noted to bring to the foreground many different historical events and movements connected to human rights in the global context, but they steer clear of the rights of persons belonging to indigenous peoples in the local context (Nolgård et al., 2020). Researchers have noticed, yet not studied in practice, how teaching and learning about the missing dimension that is the past, present and future of the Swedish indigenous peoples may result in students appreciating values of cultural diversity and attaining a sense of shared responsibility and a global awareness (Osler, 2015; Nolgård et al., 2020). Teaching about historical change may thus enable transformative social change.2

Research attending to the concept of historical change has concluded that history often is presented by teachers through a plethora of various past events in the classroom, with the potential consequence that students may not see change as a construed continuous process of events (changes), but rather as isolated episodic events of change (Lévesque, 2008). In addition, history education researchers have debated what events to bring to the fore as historically significant in school history, and also what sets of criteria might be deployed by students to apply judgement about the significance of a historical event – that is, why, how and in what ways event(s) and human experiences of the past implicate the present and future (see Arthur and Phillips, 2000; Counsell, 2004, 2011; Davies, 2011). Although interesting, the question of historical significance and models for teaching and learning relating to historical explanation is beyond the scope of the present investigation, and thus this paper will not offer an in-depth analysis of students’ use of second-order concepts (for such an analysis in the context of high-stakes history tests, see, for example, Samuelsson and Wendell, 2016; Nolgård and Nygren, 2019). Research on students’ narrational practices of historical change has concluded that a basic understanding of chronology is key for students in order to fully grasp complex ideas of interdependent concepts such as continuity and change, cause and consequence, or progress and decline (see, for example, Levstik and Barton, 1996; Lévesque, 2008; Nersäter, 2014). While many studies have concerned onto-epistemological, theoretical and historiographical underpinnings of change, and have concluded, as Keith Barton (2001a: 882) eloquently puts it, that ‘ideas about history are profoundly shaped by the cultural contexts in which they arise’, fewer studies have engaged with students’ understandings and narratives of change from a sociocultural point of view. Although explored empirically to a lesser degree, there are studies of students’ understandings of historical change and specifically the agents of change that may inform this inquiry. More precisely, previous research has noted how young students may attribute change to either changes in material culture (inventions and new ideas) or to changes in social relations – to attitudinal shifts among individuals, or to collective action and changes in social institutions in society (such as law and jurisdiction) (Barton, 1997, 2001b; Barton and Levstik, 1996; Nolgård et al., 2020). These findings align with the change approach to history education discussed above, which suggests that agents of change may be found on different levels (Løkke Rasmussen, 2013; Lücke, 2016), ranging from the individual to the nation state to international organisations.

Altogether, the body of research in this literature review points to the need for further studies concerning how history education can better scaffold students’ understandings of intercultural perspectives, diversity and human rights within hot historical topics and difficult histories. This study may offer a contribution to that implicit call.

Implications for investigations of students’ narrational practices of the Swedish Roma past, present and future

Forcing students to consider the past, present and future of the Swedish Roma minority in a national test may not only be interpreted as a way for the authorities to direct attention to state redress through history education, but it also accentuates that the knowledge of this past may be regarded as important knowledge in schooling. Regarding this notion, research has argued that a focus on difficult pasts and the development of minority rights – examples of historical change – in the local context may empower students to make decisions and become action-competent citizens in the present and future (Barton, 2001a; Ahonen, 2012; Osler, 2015; Lücke, 2016). The research presented here also shows how teaching and learning about difficult pasts through state redress implicates students’ identities in such ways that it also has the potential to disempower young learners (Löfström, 2011; Thorp, 2016). It is important to bear this theoretical divide in mind in the present empirical investigation.

Research attending to the broad concept of change (historical change and social change) suggests that agents of change relating to a difficult past, present and future may be found on different levels, ranging from law and jurisdiction, to international organisations, to the nation state, to the majority individual, and to indigenous people themselves (see, for example, Barton, 2001b; Bajaj, 2004; Lücke, 2016; Tinkham, 2018; Sheehan et al., 2018). Thus, these findings have practical implications for the present investigation, which consequently employs the identified levels as analytical entities and codes in the analysis of agents of change in students’ narratives of the Swedish Roma’s past, present and future (see the ‘Data and methodology’ section, below).

Setting and context: The intended curriculum and the national history test

On the topic of human rights, the national compulsory curriculum, LGR 11, states that each student should be able to: ‘determine their views based on knowledge of human rights and fundamental democratic values, as well as personal experiences’ and to ‘empathise with and understand the situation of other people, and develop a willingness to act with their best interests at heart’ (Skolverket, 2011: 10). Furthermore, schools are responsible for ensuring that each student, on completing compulsory schooling, ‘has obtained knowledge about the cultures, languages, religion and history of the national minorities (Jews, Roma, indigenous Samis, Sweden Finns and Tornedalers)’ (Skolverket, 2011: 11). This is emphasised in history education by bringing to the fore ‘historical perspectives on the indigenous Sami and the position of other national minorities in Sweden’ as core content in secondary school history (Skolverket, 2011: 213). By the end of secondary school, students should also be familiar with different historical concepts about historical thinking, historical empathy and historical consciousness, such as continuity and change, historical explanation, criticism of sources, identity and the use of history (Skolverket, 2011).

To safeguard the implementation of core content and second-order concepts, a national history test was introduced in 2014. Albeit serving the purpose of a tool for quality assurance and accountability, the test is primarily said to be constructed with the teacher in mind, namely serving the purpose of supporting the teacher in assessing students’ historical knowledge. In the highly decentralised Swedish education system, the responsibility for instruction, assessment and the award of grades lies with the teacher, and the national test is no exception (Klapp and Cliffordson, 2008). Therefore, the test comes with rigorous and detailed assessment instructions. The test is constructed by a group of expert scholars at Malmö University, on behalf of the Swedish NAE, in close collaboration and dialogue with history teachers.

Data and methodology

This paper analyses student responses to one essay question from the national test in history in 2014. The test was called ‘The Development Line of Intercultural Interaction’, and it focused on the Roma peoples’ situation in the past, present and future. The test was composed of a handful of multiple-choice questions and three essay questions, designed primarily to test and stimulate historical thinking and empathy skills (see Nolgård and Nygren, 2019 for an analysis). The test was taken by about 25 per cent of all Swedish Year 9 students (ages 15 and 16). This particular data sample was collected and copied by the author at the NAE archive, located at Malmö University, Sweden. In total, the NAE archive received 575 tests, of which 317 were complete with student and assessment details. In turn, 293 students answered the final essay question, which serves as the basis for analysis in this paper. The data compiled from 293 tests come from 129 municipalities and together represent all 21 counties in Sweden from the far north to the south. The analysed tests are samples from students born on the first of each month and sent by their respective teachers to the NAE archive. This sample is thus to be considered a statistically assured sample. The gender balance in this sample was 53 per cent males and 47 per cent females. (The students were ascribed their gender by the teachers who sent the history tests to the NAE archive.) The assignments were handwritten, and they were transcribed into qualitative data software. The student accounts and quotations presented in this article were originally written in Swedish and were translated by the author. Close attention was paid to each student’s response in the translation process in order to make sure that the English translation reflected and captured the vocabulary and jargon of the original text.

In the analysed essay question, the students were tasked with considering the Romani past, present and future by utilising the disciplinary concepts of continuity and change in order to strengthen their argumentation and reasoning, as can be seen in Table 1. The words of reconciliation uttered by the former Minister of Integration Erik Ullenhag (2012) form the springboard for the assignment:

The analysed essay question and grading criteria as found in the national history test

| Title | Instruction | Grading criteria |

|---|---|---|

| The Minister of Integration reflects on the future |

Use the reading material for tasks 13–17 when you solve this task!

Task: Use the concepts of continuity and change, and reason about possible extrapolations of the situation for the Roma people living in Sweden. Provide examples from the past and present to support your line of reasoning. | E – You describe a possible extrapolation of the situation for the Roma people living in Sweden. You connect some of the sources to the given extrapolation. You use either the concept continuity or change in a correct way. C – You describe a possible extrapolation of the situation for the Roma people living in Sweden. You connect several of the sources to the given extrapolation. You use both the concepts continuity and change in a correct way. A – You describe some possible extrapolations of the situation for the Roma people living in Sweden. You connect several of the sources to the given extrapolations. You choose the most reasonable extrapolation and give reasons for your choice. You use both the concepts continuity and change in a correct way. You show what these concepts mean by making use of examples from the past or the present that relate to the task at hand. |

In today’s Sweden, Romani people live in huge alienation and discrimination, and prejudice is the reality they live in every day. We have a past and a present to feel ashamed of concerning the Romani people. Now, it’s about doing what’s right so we don’t need to have a future to be ashamed of too.

Using different approaches to text analysis, the analysis combined an iterative and abductive coding with hermeneutical readings of the students’ texts (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Creswell and Plano Clark, 2017). Moreover, the analysis was conducted using qualitative and quantitative data software (NVivo), and was well documented through memoranda. The analysis of the students’ answers was conducted in five steps, following the process shown in Table 2. In a primarily qualitative study, it is impossible to illustrate the entire set of data upon which conclusions are based. The conclusions that are presented in the findings section may therefore be seen as an attempt to cluster or summarise views present in students’ responses. Throughout the study, quotations from students’ responses that represent various views on the history of the Romani and their rights are provided to illustrate a richness of perspectives, and to provide the reader with an understanding of the evidence (that is, the student narratives) on which the conclusions are based.

Overview of data analysis

| Step | Aim | Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coding and identifying the narratives of continuity and change that students bring forth in their responses. | The codes were developed in an iterative and inductive process, where close attention was paid to the text in order to capture the richness of perspectives in regard to the narratives of continuity and change. These perspectives are presented in the following section of this article. |

| 2 | Coding the agents of change in these processes. | The codes were developed in a multi-step abductive process. Drawing from the intercultural notion of a shared responsibility for Roma rights, guarantees for Romani human rights were identified through a set of predetermined agents: the EU and/or other states; Swedish law and jurisdiction; the Swedish state; the individual; the Roma. Thereafter, the responses were coded in regard to agency in order to map what agents are subjects in the processes of continuity and change. In a bid to strengthen validity and reliability, two colleagues familiar with the theories and concepts employed in this study conducted an inter-reliability test on a small random sample after Steps 1 and 2 of the analysis. The agreement of coding was 90 per cent on the level of phrases. The uncertainties regarded two cases of distinctions and overlaps between the ‘Swedish law and jurisdiction’ and the ‘Swedish state’ as agents of change. These cases were discussed thoroughly, and were addressed by revisiting the codes in order to safeguard reliability. |

| 3 | Identifying and coding other tendencies and themes. | In an inductive fashion, codes were developed for all other possible themes brought to light by the students: ‘The altruistic Swede; the mean Swede’, ‘Roma integration; Roma assimilation’, ‘a dark past – a bright future’ and so on. These themes are used throughout this text as a structuring principle of the data analysis. They also serve the purpose of clustering views visible in many of the student accounts. |

| 4 | Analysing the interplay between different codes of continuity, change and agents of change (and all the other set of codes). | At this stage, the Jaccard similarity coefficient was used in order to compare similarity – and diversity – between the set of codes. This similarity metric enables an analysis of non-linear correlation between the set of codes – that is, to inform the researcher of whether, for example, the continuity of oppression and change/no change occur at the same time, and how they may interplay. |

| 5 | Analysing each student text hermeneutically. | At this stage, every student text was analysed hermeneutically in order to understand and interpret narratives of change and continuity. The hermeneutical readings were inspired by Ricoeur’s notion of a ‘hermeneutical arc between explanation and understanding’, that is, a critical or alethic understanding of hermeneutics (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2009: 92; Ricoeur, 2016). |

Like most studies, this study has certain limitations. First, the analysis is limited to students’ written responses. This means that it is impossible to link students’ responses to history educational practices within schools. Second, the prompt to the analysed assessment task, through its somewhat leading quotation from a government official, may provide students with a clear premise for an acceptable narrative pertaining to, for example, change. Also, like any document-based assessment, such as the Advanced Placement Test in the US or the GCSE in the UK, the supporting historical documents may influence what the students write, as they must use documents to support their narratives. Nevertheless, one has to bear in mind that this test is preceded by nine years of schooling and history teaching (including content about the history of minorities and human rights). Whether taught ‘within’ or ‘outside the box’, this teaching and learning of history is conducted within a national history culture, which arguably influences the histories that students narrate in an even more profound way (see, for example, Goldberg, 2017; Porat, 2004). Although we must acknowledge the fact that the test may prompt and stimulate certain narratives more than others, one may argue that this fact is inescapable due to the nature of tests and test construction.

Findings

As the students considered the difficult past, present situation and future of Romani peoples and their human rights, a myriad of narratives unfurled. The analysed assessment task prompted students to consider this chronology using continuity and change as structuring principles. This section will be organised accordingly. Subsequently, agency and agents of change relating to Roma history and rights in the past, present and future will be explored within two subsections.

A continuity of oppression

Prompting students to narrate the history of the Swedish Roma peoples and their human rights by utilising the disciplinary concept of continuity resulted in one prominent but complex narrative of oppression, which was written by 196 of the 293 students. Referring back to previous sources in the test to support their arguments, the 196 students collectively portrayed the state as the oppressor and perpetrator in the past. This phenomenon is illustrated in this student answer:

The Roma have been discriminated against ever since the 17th century in Sweden and I can see that clearly as source 1 in task 13, The Gypsy Law from 1637, proclaims that the Roma would be hanged if they did not leave Sweden immediately. It reads that the state will hunt them down, confiscate their belongings and sentence them to death by hanging. That is a clear violation of human rights from the state and perhaps also the people of Sweden. And it has not changed since, because Växjö municipality currently refuses to raise the Romani flag on their international day. (247)

As this quotation illustrates, this student characterises the state as the oppressing force of the past. Through corroboration, the student also expresses judgement about the state’s actions in the distant past and in the present. In the same vein, 57 students underscore the present event, where Växjö municipality refused to raise the Roma flag on the international day, as an example of a continuity of oppression by the state. Moreover, 135 students explicitly address and acknowledge xenophobia and racism against the Swedish Roma today. In these narratives, right-wing populism and neo-nationalist ideology are underscored as perpetuators of oppression towards the Swedish Roma. However, most students link xenophobia and racism towards the Roma to individuals, rather than to the state. Such individuals are construed, for example, as: a municipal commissioner refusing to raise the Roma flag on the international day (N=118); a xenophobic person (N=43); an individual belonging to a blinkered generation of adults with preconceptions about the Roma (N=36); a voter for the nationalist party, the Sweden Democrats (N=27); or a grandparent with outdated views about human beings (N=5).

Narrating the development of human rights for the Roma: A dark past and a bright present

Engaging with the development of human rights for the Roma people, 258 students (88 per cent of the students) narrate a dark history and a bright present for the Romani. This may thus be considered a grand narrative. This student account provides a representative evidence-driven narration of the development of Roma peoples’ human rights:

The future for the Romani looks brighter compared to the 17th century when the Roma was forced to leave the country or be beheaded. Slowly, but surely things turned to the better for them. But in task no. 14, Singoalla [The Wind Is My Lover, a novel by Viktor Rydberg] from 1857, we are told they are thieves. The special treatment/discrimination continued well until the 1940s and 1950s when they had to go to special schools, which besides was a tent. They could not afford anything at the time, but there were kind Swedes helping them. The change is drastic. The continuity is that Roma people to this day are seen as shifty and that they are poor and undereducated. Since the law on the protection and furthering of minority culture (2010) passed it has become much better for the Roma and their children are allowed to attend school. Many Swedes have changed their perceptions of the Romani and they are treated better by the people so it is a huge change. (18)

While all the students discuss prejudice and oppression in one way or another in their narratives of a development of human rights for the Romani, a group of 49 students (17 per cent) contrast the past with the present, stating that human rights for the Romani are now established. From a historian’s point of view, these two narratives encapsulate the notion that history follows the dramaturgy of a march towards greater progress or enlightenment, that is, a Whig interpretation of the past (see Butterfield, 1965).

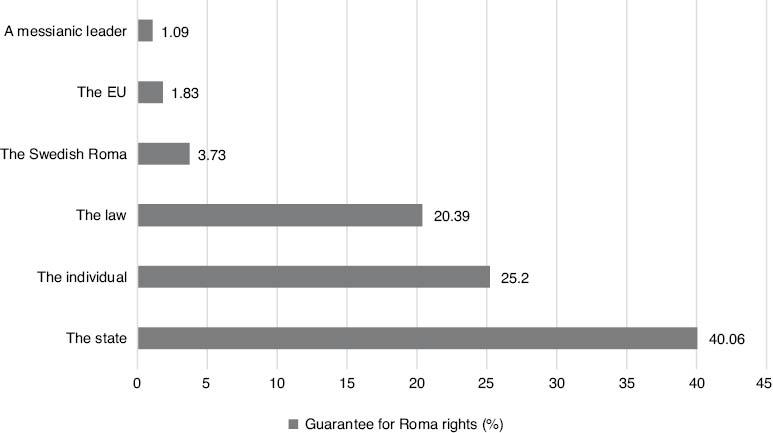

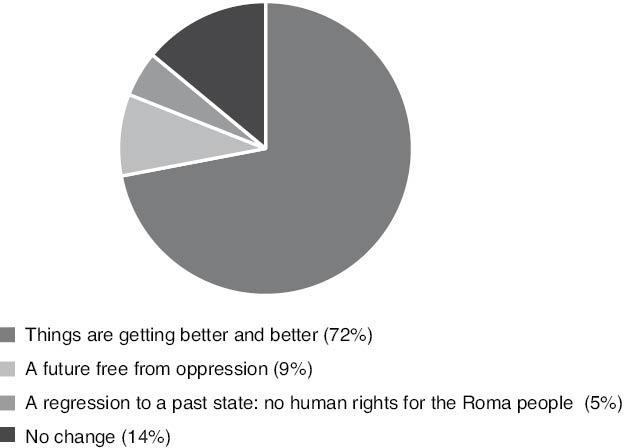

Narrating change

As the students considered the past, present and future of Romani peoples and their human rights, four prominent narratives of change unfolded (see Figure 1). All four narratives are equally present among all students, regardless of grade, and they constituted 86 per cent of the total amount of text in the student accounts. A Jaccard correlation coefficient analysis of grades vis-à-vis the manifested narratives of change showed no statistical correlations of significance. These four narratives are equally present among the whole cross-section of adolescents. The question of grades in relation to specific prompts in assignments, or in relation to skills and values, is, however, interesting, although beyond the scope of this paper. In addition, an analysis of non-linear correlations between these narratives of change shows that they are brought forward one at a time and not intertwined. In line with that finding, rather than considering multiple outcomes, students narrate what change scenario they find most plausible. These narratives will be explored further in the following section.

Prominent narratives of change manifested in the student texts, displayed by percentage of coding coverage (source: author)

By using corroborating sources in the national test to support their narratives, 186 students narrate an increasingly improved situation for the Romani peoples when it comes to their human rights. This narrative alone constitutes 61 per cent of the total coding coverage of the students’ texts, and it is exemplified in this student account:

In the future, I think that the situation of the Roma in Sweden will get better. What leads me to that conclusion is that Sweden, as time has changed, has become more tolerant and accepting towards the Romani. I do not, however, believe that this change will be radical, but rather that acceptance and tolerance is a continuity and that we in a number of years will have fully accepted them. (202)

Many students also pay attention to people in positions of power, such as politicians, when narrating this change:

I believe the situation for the Roma people will get better. Erik Ullenhag wants to make the society a better place for the Romani and he is a man of power. If you look at the timeline you may see how they [the Roma] had a tough time in the past and how it has only got better and better. Judging by the development, that makes me think that their situation will get better and better. (153)

This particular manifestation of change is thus expressed in the student texts in a myriad of ways, for instance, through the agents of change. In addition, a fairly large proportion of the students (N=53) involve themselves as actors of change, or express care through reassurance and feelings of hope, in line with this account:

In the future I hope and believe that the Roma are going to be a more integrated part of Sweden. That they won’t live in alienation from society as they did before. I hope they may live without fear of being expelled from Sweden. Looking at the progress made makes me feel hopeful. (189)

Another position on agents of change for Roma rights is a belief in the capacity of Roma people themselves, a view expressed within this narrative by 24 students, including:

The future will definitely get better for the Romani. If the Roma have managed to survive in Sweden during all these years and have got access to education and schooling, the Roma people will counter the exclusion and discrimination with the help of the Swedish people. (126)

In relation to this change, 30 students look to a future free from oppression, with statements such as ‘in our common future, the Roma people will face a brighter future and live as any other Swede without consequences and discrimination’ (248). In light of the lack of interest in considering multiple perspectives at once, discussed above, the narrative of things will get better and better may be perceived as a grand narrative about the development of Roma rights.

Change is not going to come

Looking to the future, 44 students narrate a future where there will be no change in the situation for the Roma peoples. Often, these narratives articulate a subtle critique directed towards various agents of change. The target is often an unnamed collective, as can be seen in this student narrative:

Everything points to that there is going to be no change at all. I think so, since there has been a lot of talk and no action in regard to change. In the future, I believe the situation for the Romani in Sweden will be the same as it always has been – horrible. (1)

While condemning actions, or the lack thereof, in the past and present, this student distances herself from being an actor. In contrast, and more commonly, students tend to include themselves in a construed majority of we, in line with the notion of a shared responsibility, as manifested here:

I believe most sources point to that we’re still going to be critical and racist towards the Roma. Because humankind has not overthrown and countered racism against Romani in such a long period of time, I doubt we will be able to do it within the next couple of centuries either. (227)

Along these lines of reasoning, students frequently shine a light upon a pervasive lethargy among the Swedes regarding Roma rights, as expressed here:

In the future, I believe things will remain the same; we know we need to do something but nothing happens since there are so few people who have dared to stand up for the Roma people. (217)

Within this particular narrative, we can see a complex duality about how the nation state is portrayed. One student states that the situation for the Roma will remain as it is, and argues: ‘I do not think the state takes them very seriously. Education, health care and economy always come first’ (147). In the same manner, another student adheres to the use of a majority we, and formulates what may be perceived as an explicit critique of the aforementioned lethargy:

Regardless of how much we want change things won’t change. As seen in task 17, power dimensions and money are the strongest factors as to why not. We say we want ‘a new Sweden’, that we should not need to be ashamed of our future, but what future? We cannot afford waiting the way we do. The minorities are long gone if we do not act now! I am certain that the situation for the Romani won’t be better in ten years from now. And that is because we refuse to let go of the security blanket and stand side by side with the Roma for change. Money is, as previously stated, an important aspect. Especially today as the world is struck by recession. At times when we can afford change, we care too much about our capital and do not give a shit about acting for change. When we find ourselves in recession we can’t. That is why the situation for minorities is a continuance. When a country is in a bad state, nationalist parties and mindsets grow stronger. If I didn’t know better I would blame REVA3 and the Sweden Democrats, but I know better than to put the blame on them. We humans are cowards and I am tired of our indifference and the fact that we do not dare to stand up for anything these days. It is that kind of behaviour which makes discrimination a continuity and stands between us and change. (282)

This student construes a narrative where the citizen has their hands tied behind their back by a capitalist state. By pointing out structures of power and money as reasons for the lack of interest in Roma rights, and calling for individual action, the student implicitly expresses the notion of a shared responsibility for Roma rights, suggesting an interdependence between the state and the individual.

State regress: The pendulum swings back

In 18 of the students’ narratives, the future will see the current state of rights come to an end. The majority of these narratives link this extrapolation to the emergence of a new wave of extreme right-wing ideologies in general, and the growing support for the Sweden Democrats in the 2014 national elections specifically, as exemplified in this student account:

Things might get worse. For example, if a right-wing extremist party such as SD [Sweden Democrats] would get their reform proposals through. They believe that the Roma is a threat to Swedish culture and economy. If this happens, we will regress to a situation reminiscent of the 17th century with expulsion of ethnic minorities and ethnic cleansing of immigrants. This will inevitably prevent the situation for the Romani to change. They will get much less of a dignified existence than their forefathers and theirs before them. (257)

It is noteworthy that in these narratives a specific political party becomes emblematic of a leaning towards a hostile, conservative society of cultural homogeneity, where even the expulsion of minorities and ethnic cleansing of immigrants may occur.

Agents of change

Narrating change, the students underscored the importance of six different agents of change. These guarantees for Roma peoples’ human rights are manifested in the texts to varying degrees, as shown in Figure 2. In the student narratives, the state is identified as providing the single largest guarantee for Roma rights in the present and future by 122 students. This is chiefly done in four ways: (1) by narrating a development, where Sweden is credited for giving the Roma certain welfare benefits (health care and schooling); (2) by emphasising the weight of economic and labour policy supporting the Swedish Roma; (3) by underscoring the role of the state as providing a guarantee of education – about, as well as for, the Roma; and (4) by praising the nation state for its role in sustaining human rights for the Roma.

For the purposes of this study (and in Figure 2 specifically), the state is separated from the law, despite having legislative powers. This is because the students, in their responses, explicitly underscore the frameworks and laws supporting minorities on the one hand, while on the other hand stressing the importance of an interventional nation state or politicians as role models. Of late, Scandinavia has seen an increase of juridification processes with regard to minority politics, where precedential rulings, one may argue, serve as the basis for new decisions about minority politics to a greater extent than politicians in the service of the state (see Radio Sweden (2020) for readings on the Girja trials as a contemporary example).

Many students also critique the role of the state, arguing that the state only shows a veneer of concern for human rights, rather than actually looking to sustain Roma rights in the present and future. Therefore, 81 students emphasise the weight of individuals as agents of change. The rights of the Roma are narrated to be guaranteed by: (1) individual Swedes in the past and present, helping the Roma in the spirit of altruism; (2) individuals who organise for social justice, human rights and peace in the present; and (3) by an open-minded younger generation of individuals brought up with a view of humanity in line with the notion that all human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. (This exact formulation is used by 31 students, without specific reference to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.)

The weight of laws sustaining human rights for minorities as guarantees of the Roma’s rights is stressed by 79 students. The majority of these narratives show great faith in the revised framework and law on the protection of national minorities and minority languages, arguing that legislation paves the way for positive change. In conjunction with the narrative of law and legislation as guaranteeing the Roma’s rights, 38 of these students acknowledge the primary function of the law as a defence of the cultural right, that is, embracing the specificities of Roma culture, and developing and furthering Roma culture. As part of a development of rights, the law is also identified as an agent of change by the acknowledgement of the legislative power of the nation state.

Altogether, 24 students call attention to the Roma and their rights by: (1) highlighting the perseverance and fighting spirit of the Roma in the struggle for schooling (8 students); (2) narrating scenarios where the Roma peoples and Swedes join forces in demonstrations for Roma rights (6 students); and (3) praising the perseverance of the Roma people throughout years of oppression (10 students).

Moreover, 5 students view the European Union and its member countries as providing a guarantee for Roma rights. What is common to all of these student accounts is that they suggest that the situation for Roma people in Europe has to be a shared responsibility, and that Sweden as a country should further the cause of Roma human rights in the European Parliament.

In addition, 4 students narrate a past, present or future where Roma rights are dependent on a messianic leader. The actions of Raoul Wallenberg during the Second World War are recalled by 1 student, who argues that such a prominent figure may influence others to work for the common – and Roma – good; 2 of the students argue that the former Minister of Integration, Erik Ullenhag, is characteristic of such a figure. The fourth student emphasises the need for a messianic leader, stating that ‘we need a new human like Nelson Mandela in order to make the Roma people accepted in Sweden. Someone who can really order the government to take action and question their inaction’ (174).

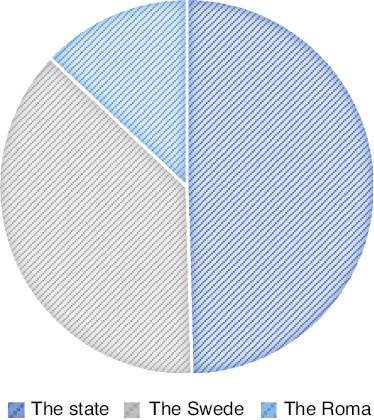

Positioning themselves and others on agency and ethical standpoints

As the students consider the past, present and future of the Romani in Sweden, they manifest agency in different ways. The investigation shows how agency is attributed to three different actors: the state, the Swede and the Roma. In Figure 3, the groups given agency are presented by the number of coding references.

It is evident that the analysis of agency indicates a strong alignment with the distribution of agents of change. What is common for all these accounts is that the students play an active role in disseminating Roma history by explicitly sharing their standpoints (visible in 430 unique references), rather than producing neutral narratives (see Thorp and Vinterek, 2020). Pertaining to agency, the analysis reveals a conflation of historical agents, wherein the state and the individual become intertwined. This is manifested in the answers by the use of the inclusive first-person pronoun ‘we’ (used by 120 students), as exemplified in this statement:

How may we learn from each other and learn to accept one another? As past and present events have shown, things have not changed. We, in Sweden, still have limits for how included they may be. They’ve never been included in the history of our nation, never felt welcomed or even seen as people and this has to change. If we only could see beyond the epithet ‘Roma’ and get to know the person behind, we would stop pointing out the Roma as a group every time someone of Roma descent is making criminal offences. Just because one person did something does not mean that a whole group has to take the blame. They must prove their innocence, that they’re not thieves, in today’s society and ‘a Swede’ does not have to prove anything. Their rights must be regarded as a matter of course and not something they have to be ‘grateful to have’ or ‘appreciate’, because they are basic principles and should be regarded as such. (285)

In addition, most students express transformative views as they give agency to the state. This is often done by stressing a need for further welfare benefits concerning housing, education or public celebrations, with many students stating that ‘the state does not do enough for the Romani’. There are also students who emphasise ideals of democracy and rights as fundamental parts of the modern nation state:

I think we should learn from the past and make a real change for the Romani so the situation will be better for them in this democratic society which Sweden is. And I think the world can learn from our example. (260)

Regarding individuals being given agency, most statements concern prejudice or xenophobic views among individuals. Doing so, 61 students use an excerpt from the novel Singoalla by Viktor Rydberg (1865) as historical evidence to advance arguments about the ever-present prejudice that Roma people are thieves. Moreover, students give individuals agency as they narrate Swedes as providing guarantees of Roma rights, or as they make moral judgements such as: ‘we shall not oppress anyone, we shall welcome them!’ (150); ‘we must have justice now!’ (225); and ‘all people – Swedish or Roma – should be treated equal!’ (262).

The vast majority of the students guard the rights of the Roma people to further and develop their own culture, and almost unanimously emphasise this as a positive and unifying phenomenon from an intercultural and integrational point of view. There are, however, student voices that question this view and argue that the Roma must adapt and assimilate. This tension becomes most salient as the Roma are attributed agency. Students state that the Roma must ‘accept and succumb to Swedish values’; ‘dress as normal people’; ‘make better efforts to collaborate and do something about their situation’; and ‘actually show that they want to be Swedish’. In relation to the sources that are presented throughout the test, 20 students also attribute the Roma agency in narratives of their struggle for schooling and rights during the twentieth century.

Roma integration and assimilation: An ethical divide

In line with theoretical notions of historical culture and public memories (Löfström, 2011; Elmersjö, 2015; Thorp, 2016), 31 students explicitly underscore the importance of the majority acknowledging Roma culture as an act of inclusion and integration. A majority of these students point to public celebrations of important events for the Romani, such as in the statement: ‘we should regard their international day as an important day of great symbolic value to us all, since we actually belong together these days’ (216). Similarly, another student highlights the importance of ‘raising the Roma flag on the international day as a way of sending a clear signal to everyone that the Roma is an integral part of our country’ (246). A third student encompasses this view by suggesting that ‘we can celebrate their international day together with them and make it into a national holiday, a celebration to the people, paying love and respect to the Roma’, while also stating that ‘we could also learn more about Roma history and culture in school, which would result in children learning to understand, tolerate and appreciate Roma culture’ (270). Education, both formal and informal, as a means to overcome prejudice is highlighted by 12 students; for example:

We must keep on trying to overcome xenophobia and hatred towards the minorities in Sweden. There are many ways in which this may be accomplished, e.g. through teaching and talking about the minorities so more people can acquire knowledge and an understanding. One could introduce a celebrational special day for the minorities, the same way we’ve the Pride event. That way, I am sure the situation for the Romani will turn to the better in Sweden. Because it is all about smashing prejudice and that is best done with knowledge. (291)

Through their narratives, these students manifest a willingness not only to embrace minority culture, but also to become co-creators of social memories together with the minorities. Part symbolic act and part practice, this may, in line with theories of historical culture, hold the potential for constructing new collective memories, and thus for changing historical culture from within.

There are, however, students who disagree with this line of reasoning. In line with the findings on Roma agency, 37 students construct narratives where an important part of Roma integration lies in assimilating: the Roma should speak Swedish, and should appreciate and live by ‘Swedish values’. Within the group of students emphasising assimilation, there are 14 students manifesting thoughts of xenophobia or nationalism in their narratives to a greater extent than other students, making statements such as ‘we must make sure to keep Sweden Swedish’ (41), and ‘we should close our borders and push the gypsies out’ (120), or narrating passages of how they have seen Roma people shoplift in grocery stores. In light of the theoretical notion of powerful groups (Löfström, 2011; Elmersjö, 2015), this advocation of assimilation may be viewed as an imperative to the Roma: forcing them to suppress their collective memories of a minority past, a history culture, in order to assimilate, and thus to become incorporated into the discourses of a perceived national majority group.

Discussion

This study intended to examine how students make sense of the difficult past, present situation and future of the Swedish Roma. In this section, the findings presented above will be discussed in the light of notions of historical justice and change.

The investigation makes evident that a vast majority of students construe a narrative wherein a nation imbued with antiziganism transforms into a prosperous nation when it comes to ideals of democracy and a development of fundamental human rights for the Swedish Roma: a grand narrative of the nation state and a development of cultural interaction, which all the while is getting increasingly better. Along these lines, most of the students emphasise the weight of the nation state as an agent of change and guarantee of rights for Roma in the past, present and future. In what has been described as an era where nation states are in decline (Olick, 2007; Elmersjö, 2015), this cross-section of students thus expresses a strong belief in the interventionist nation state through their narratives of historical change. The document-based query sources provided as supporting evidence for students facilitate, one may argue, a certain chronology to the narratives of rights, wherein the state is inevitably construed as an important agent of change. In light of historical justice, redress politics and reconciliation, one may regard the analysed test as teleological in its nature and purpose, that is, that this test constitutes an example of history education in the service of the nation state (as in, by the state, for the state). Against this backdrop, it is noteworthy how the test is constructed without referential statements about violations of Roma rights in the present and recent past, for example, the forced sterilisation of Roma people that took place between 1934 and 1976. In accordance with theories of narrational practices in history education (White, 1973, 2014; Parkes, 2013; Elmersjö, 2015), one may view the selection of sources as a political act, with the possibility of influencing the extent to which the students regard the nation state as a guarantee of Roma rights in the present and future. Constructing a national test such as ‘The Development Line of Cultural Interaction’ may, in light of historical justice and state redress, also be viewed as a hegemonic practice in itself (see Barkan, 2000; Löfström, 2011; Carretero, 2011; Elmersjö, 2015; Neumann and Thompson, 2015).

Although students express dismay over the past in general, and the nation state’s actions in particular, the prevailing image of the nation state is that of a country defending cultural rights, human rights and democracy (see Osler, 2015). In relation to this finding, one can sense the move towards a shared line of reasoning, in that 120 students use the first-person pronoun ‘we’ in the construction of their narratives of the past (see Samuelsson, 2017; Thorp and Vinterek, 2020). The use of ‘we’ signals a certain closeness to the past and affinity with the majority: ‘we’ should be ashamed of ‘our country’ and ‘our past’. While that aligns with the thought of reconciliation, one may, from a history culture perspective, argue that the students thereby construe Sweden and the Swede in the present as intertwined cultural and political entities, both of which further values of democracy and rights.

In spite of this, the empirical investigation shows that many of the students accentuate the importance of a shared responsibility concerning Romani peoples’ human rights. Through narratives challenging the often-told history of an uncontroversial development towards improvement, this sample of students reflects how an intercultural democratic society is a common endeavour, which largely depends on participation from the majority of Swedes, the state and the Roma. One might argue that students answer the assessment task in the hope of earning a good mark, and that they do not necessarily agree with everything they have written. Nevertheless, it is clear how students, through their narrational reconstructions of the past, present and future, realise and recognise Roma rights in several ways. On the one hand, they do this by describing historical changes regarding Roma rights; on the other hand, they express not only hope for future change, but also a willingness to participate in the common endeavour of sustaining human rights for the Swedish Roma. In addition, their narratives bear witness to an understanding that individuals and the state may suppress oppression through joint actions. From the point of view of state redress and historical justice, these findings may, in fact, suggest that it is possible to instil and realise a sense of shared responsibility for Roma peoples’ human rights through a state-sanctioned national history test – and thus counter the perceived silent historiography (see Mattlar, 2014, 2016; Osler, 2015; Nolgård et al., 2020).

Bearing in mind that the minister’s statement of apology in the assessment task is given in the name of the state, while also referring to ‘our nation’s past’ and ‘our history’, this calls for what Löfström (2011) describes as a cultural and political solidarity by the students. In order to become empowered with this notion of transformative change, students must identify with the Swedish nation and majority historical culture, and accept the indebtedness to the difficult past of the Swedish Roma. This empirical finding raises further concerns regarding those students whose history cultures overlap, and who transcend cultural and historical boundaries. Since being part of the national community of memory is key to becoming empowered and action-competent through this subject matter, for example, students who identify as Roma-Swedes may find themselves in a ‘cultural-political limbo’ (see Löfström, 2011), feeling incapable of entering the national community of memory or feeling the need to abandon their collective minority memories of the past in order to assimilate. In relation to this observation, 37 students construct xenophobic narratives, where the importance of assimilation is accentuated. This view may be regarded as a manifestation of the excluding potential that an official apology and history education, driven by notions of historical justice, reparations and reconciliation, may have, namely that citizenship and rights are given an ethnic twist by a reproduction of symbolic and mental group boundaries and structures of the past. Instead of an enhanced appreciation for cultural diversity and empowerment, this national history test may, for these students, lead to stronger ethnic group identities.

Furthermore, it is noticeable how 61 students use an extract from the novel Singoalla by Viktor Rydberg (1865) to support their reasoning regarding prejudice in both past and present. In addition, none of the 293 analysed student texts scrutinised the source and considered its fictional nature. This unreflective stance towards sources may be seen as problematic for many reasons, and it can be interpreted as presenting two similar but somewhat different challenges to be addressed in future history education research and practice referring to difficult pasts. The first challenge is of a historical thinking nature: as an expression of a perceived lack of critical historical thinking and sourcing skills. By this logic, this could be addressed by paying closer attention to the act of sourcing in the history classroom. The other challenge is more closely related to notions of historical culture and the pursuit of justice through history education. In accordance with Chinnery (2019), this conflation of fact and fiction may potentially be overcome by raising an awareness of historicity in the histories we narrate, and in how we perceive and use said narratives. With a better understanding of historicity among young learners, it may become easier for practising history teachers to illustrate how different history cultural aspects affect how we approach and reconstrue difficult pasts.

As a closing remark, it is evident how this attempt at state redress has seeped down and made its imprint on the students’ narratives. As stated above, making students consider this difficult past may be interpreted as a way for the authorities to direct attention to this subject matter (see Zembylas, 2017; Sheehan et al., 2018; Chinnery, 2019). Regarding the notion that learning about historical change may lead to transformative social change, one may say that this test has the potential to equip students with important intercultural knowledge about a difficult past and a sense of a shared responsibility for human rights in the present. Steeped in perspectives of historical justice and reconciliation, this historical encounter holds the potential to further an appreciation for cultural diversity and to instil intercultural values such as a sense of shared responsibility. From a schooling and citizenship point of view, this may be viewed as a desirable goal. In light of this goal, and in relation to the findings, it may, however, be worth considering whether history education through historical reparations and reconciliation really is the best means by which this may be accomplished. This is especially the case if empowering all young learners to become action-competent – that is, teaching for change – should be an objective and an integral part of social studies and history education. Further empirical research is needed to explore how alternatives, such as different multi-perspective approaches, may support students’ sense-making and narrational practices of controversial histories and difficult inheritances. Decision-makers, researchers and teachers may ask themselves how practice can help scaffold and realise an in-depth understanding of human rights, diversity and historical justice in line with intercultural goals, without reconstructing mental and symbolic boundaries, which potentially may disempower young learners in the history classroom.