Introduction

Following the demands of students at the University of Cape Town in South Africa to remove a statue of Cecil Rhodes (SAHO, 2017), prominent institutions in the UK have begun to decolonize higher education (Chaudhuri, 2016; Students’ Union UCL, n.d.; SOAS Students’ Union, n.d.; Bretan, 2017; RMF Oxford, n.d.). These include the University of Oxford (Mohdin et al., 2020), the University of Cambridge ( Decolonising the English Faculty: An open letter, n.d.), SOAS University of London (SOAS Students’ Union, n.d.) and Goldsmiths, University of London (‘Decolonising the curriculum – the library’s role’, n.d.). Other than at UCL (n.d.) and the University of Sussex (n.d.), there are few examples of decolonization efforts in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine (STEMM) disciplines in the UK and no empirical studies to our knowledge. This presents challenges in that, as educators seeking to invite debate around decolonization and how it applies in the engineering, natural and medical sciences, there is little guidance or previous experience to follow.

It is in this context that we embarked on an initiative to examine whether, in our educational practices (or praxis), we are privileging certain perspectives over others. Our approach was data-driven and reflexive. Funded by the Vice-Provost for Education to stimulate innovation in teaching and learning, this work was conducted during a far broader process of educational reform at Imperial College London (henceforth ‘the College’).

Our aim was to understand whether biases against research from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which we had published on extensively in the past (Harris et al., 2015, 2016; Harris et al., 2017b; Skopec et al., 2020), was a concern or at all relevant in our educational practices. Initiatives involved the empirical analysis of the geographic origins of the research papers included on the reading lists of 16 modules of the Master’s in Public Health course. The findings of this analysis were compiled into reports, which were distributed to module leaders. We developed a bespoke implicit association test (IAT) in collaboration with Project Implicit at Harvard University (https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/), to test respondents’ unconscious biases between ‘good research’ and high-income countries (HICs). Together with the College’s Educational Development Unit, we delivered workshops on Examining Geographic Bias in our Curricula, where participants were given the opportunity to reflect on and discuss results of the reading list analysis and the IAT. From the workshop participants, we recruited eight volunteers for hour-long, one-to-one interviews, with the objective of illustrating challenges and barriers to including more LMIC research in their teaching materials.

Central to the decolonial debate is understanding how the dominant epistemic community has systematically negated ways of knowing and being that are not in accordance with its ideas (Boidin et al., 2012; de Oliveira Andreotti et al., 2015; Icaza and Vazquez, 2013; Mignolo, 2009; Mignolo and Tlostanova, 2006). Epistemic communities are networks of knowledge-based experts, who share the same world view (or episteme) and can create substantiated claims to knowledge, influence decision makers (Haas, 1992) and exercise decisive power (Antoniades, 2003). While members of the same community may still engage in often intense debates to generate a new consensus (Haas, 1992), there are few studies which have highlighted the antagonistic relationship between communities in different places (Dunlop, 2013). Further, epistemic communities can guide, but also constrain, practice (Wagner and Newell, 2004). If confronted with anomalies that happen to undermine their shared beliefs, members of the dominant community might withdraw entirely from a debate (Antoniades, 2003).

Previous research has demonstrated a discounting of research from LMICs (Abu-Saad, 2008; Bornmann et al., 2011; Cooper et al., 2018; Harris et al., 2017a; Pan et al., 2012; Scheurich and Young, 1997; Warikoo and Fuhr, 2014). Through centuries of HIC dominance, LMICs have been relegated to consumers of knowledge, rather than producers of knowledge (Abu-Saad, 2008), and they are seen as the subordinate epistemic community. Bringing formerly subjugated ways of knowing to the fore by challenging the dominant epistemic community’s authoritative claims to knowledge may result in a shock to that community (Haas, 1992).

Although not representative of the entirety of experiences, in this article we propose and describe epistemic fragility, which we define as an effortful reinstatement of an epistemic status quo, as a reaction against introducing ideas, narratives and research associated with decolonizing the higher education curriculum. We foreground this in particular because of its significance as a notable reaction to the reading list analysis, its resonance with similar concepts such as ‘white fragility’, introduced by Robin DiAngelo (2011), and for the opportunity it provides us, as educators, to improve practice in decolonization efforts moving forward. DiAngelo (2011) describes efforts to reinstate a racial equilibrium, following challenges to objectivity, meritocracy, authority and centrality. The decolonial movement directly reflects these challenges, calling into question not only the racial equilibrium, but also the Eurocentric epistemic equilibrium. In this article, we observe that fragility reactions may arise in response to clashes of epistemic communities, when core principles of STEMM (objectivity, meritocracy, authority and centrality) are challenged by suggesting the introduction of research outside of the hegemonic academic canon.

Decolonization is far more than the removal of statues from college campuses or the diversification of reading lists. It is our intention to describe and understand reactions to our efforts by reflecting on both confirming and dissenting voices with humility, and to explore decolonization and its place in our institution, as we believe this provides learning opportunities for others engaged in this space.

Methods

We describe an explanatory sequential mixed methods case study (Creswell, 2014: 264–88; George and Bennett, 2005: 34; Yin, 2011: 3–20) set at Imperial College London. One of the top-ranked higher education institutions nationally ( THE Student, 2020) and globally ( THE, 2020), the College has been shown to be a thought leader and ‘cognitive authority’ (Haas, 1992) in the STEMM field, driving crucial policies and serving as an expert adviser, most recently during the COVID-19 pandemic (Whittles et al., 2021).

Following widespread social justice protests over the summer of 2020, the College began to act publicly around decolonization. There have been several correspondences by the President, Provost and Faculty Chairs on the issue. Certain measures have been taken, including a fundraising campaign to support scholarships for black students, new advice and guidance for members of the university to be better white allies and the removal of the institutional motto (‘Scientia imperii decus et tutamen’, loosely translated as ‘Scientific knowledge, the crowning glory and the safeguard of the empire’) from the coat of arms (Evanson and Scheuber, 2020).

The growing realization of a colonial legacy deeply embedded within our educational and research practices is acknowledged, and the university administration states that ‘we choose not to deny that history, but [we will not] be defined by it either’ (Imperial College London, 2020). These initiatives have done much to sensitize faculty to issues of social justice, for example around addressing any colonial legacies in the university’s history, as well as consideration for a more diverse student body and the benefits that this brings. As a predominantly STEMM-focused university, the College has taken steps to incorporate humanities and social science perspectives into curricula, with undergraduates required to choose a module from beyond their discipline, and postgraduates encouraged to take additional courses to expand their epistemological and methodological repertoire (Imperial College London, 2021). Introducing natural science educators to the benefits of research methods and lines of enquiry classically used in the realm of social sciences has been an important advance to improve educational practice, as well as to prime the faculty body to the decolonization debates.

It seemed reasonable to begin with an understanding of whether or not there was a geographic over-representation of readings from HICs at all, particularly as this sort of empirical analysis tends to be missing from decolonization efforts in other institutions. Much like analysing the demographic characteristics of student cohorts to identify under-representation from marginalized groups, analysing reading lists provides a snapshot of the programme, asking whether certain geographies are represented more than others. In this way, we can better understand not what is taught, but from where we are teaching. We undertook a descriptive analysis of the reading lists used in each of the 16 modules on the 2017/18 Master’s in Public Health programme to determine the geographic distribution of literature sources. Modules included Principles and Methods of Epidemiology, Foundations of Public Health Practice, Global Disease Masterclass, Global Health Challenges and Governance and Health Economics. Reading lists were gathered from Leganto, the platform used to compile, manage and share recommended readings (Imperial College London, n.d.). We identified the institutional affiliations of authors, as a proxy for country of origin, and we collated data on first and last authors only, as these are conventionally agreed to have contributed the most to the final publication (Bhattacharya, 2010; Riesenberg and Lundberg, 1990). We were aware of the impact of this on the level of granularity of the data, but it was preferred for the purposes of expediency, given that many articles have more than 15 authors on each citation. Results were presented to module leaders in bespoke reports, using summary statistics to compare the composition of their reading list to the readings assigned on the course overall. Along with the graphical representation of the analysis, we provided module leaders with a brief outline and context for the project, which was to invite reflection on the distribution of readings in each module.

In a second phase, we ran staff development workshops for faculty from across the College aimed at sparking debates around decolonizing higher education curricula. We invited participants to reflect on what their reading lists currently look like, why they look the way they do, whether they consider it a problem and what they might do to change them. We also asked participants to consider what challenges or barriers to making changes to their reading lists they had already experienced or anticipated. In advance of each workshop, participants were invited to take an IAT as a point of departure for the subsequent discussion. Our IAT (the methodology for which has been described elsewhere; see Harris et al., 2017a) was used to assess participants’ unconscious association between ‘good research/bad research’ and ‘high-income countries/low-income countries’. Project Implicit stored and managed all collected data and made raw data available to us on request. Data were analysed using Stata SE 16.1. Data collection for the IAT is ongoing, as the link to the test is still actively being distributed to members of the College community and beyond. Our findings pertain to results up until 20 May 2020 and comprise scores for respondents from the College community only, as discussed in the ethics section below.

Following the workshops, we invited all participants for hour-long, one-to-one interviews. Of the 27 attendees at the workshops, 8 volunteered to be interviewed. Participants represented a wide array of professions (from teaching fellows to educational directors) and spanned multiple faculties and departments (such as Medicine, Physics and the Central Library). Although several of the module leaders whose reading lists we had analysed attended the workshops, none of them were available to be interviewed. Interviews sought to explore through open-ended questioning themes around attitudes and choices involved in developing reading lists, the role of the interviewee’s country of origin in identifying teaching and learning resources, and experiences around attaining geographic representation in taught programme material. Interviewees were also asked to consider the broader barriers and challenges to incorporating research from LICs in the curriculum, exploring rules and practices – both written and unwritten – that discount or omit research and practices from sources outside the Global North. Interview questions are shown in Box 1. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis was carried out separately by two researchers (MS and MF) to increase the validity of the generated codes (Braun and Clarke, 2019). A third coder (MH) was consulted periodically to help resolve differences of opinion and assist in organizing themes into a coding framework.

Interview questions

We derived the notion of epistemic fragility through synthesizing discussions held at the workshops and following the iterative nature of interview analysis. It was not an a priori decision to choose this framework at the outset of our project; rather, it emerged over the course of the case study. We draw parallels to DiAngelo’s (2011) ‘white fragility’ not because we feel it offers a perfect fit, but because, in our estimation, it offers some explanatory power and potential for further exploratory research as a conceptual framework in initiatives to decolonize curricula. Here we are concerned not with ‘white’ fragility per se, but more with an ‘epistemic’ fragility, where challenges to one’s conceptualization of knowledges and knowledge hierarchies elicit defensive moves.

Positionality

We focused our analysis of reading lists only on the Master’s in Public Health programme in the first instance because, in terms of pedagogic ‘jurisdiction’, we had a degree of control over this programme and its delivery. MH is a co-director of the programme, MS is a graduate teaching assistant and is a former student on the master’s, as is HI. We sought to balance our research team with KI and MA, of the university’s Centre for Higher Education Research and Scholarship, and MF, an educational researcher in the School of Medicine. As programme and module leads, our own practices and perspectives are offered up for analysis through a constructivist epistemology, whereby the research process and findings have emerged through collaborative engagement between the research team and other participants in these activities. While some of us were very close to the occurrences, others (such as MA, KI and MF) were more remote, and this allowed us to consider the unfolding events reflexively and from a variety of different perspectives. The research team comprised public health specialists with a track record of publications around the concept of reverse innovation in the National Health Service (MH and MS), educationalists (KI and MF) with experience in inclusive practices, an anthropologist (MA) and a social scientist with extensive experience researching knowledge hierarchies in the space of international health partnerships (HI), contributing a diverse and interdisciplinary range of perspectives in the analysis. This interdisciplinarity also meant that the team held an organic tension regarding the use of quantitative data for the purposes of decolonization. The study team’s own geographic diversity similarly influenced the viewpoints and perspectives expressed in the interpretation of the data. Three team members (MH, KI and MA) were British, with considerable experience working and studying abroad (in Brazil, Mexico, South Africa and the US), two (MF and MS) brought their perspectives from the American higher education system to the British context and another was a first-generation immigrant to the UK from Somaliland (HI).

Ethics considerations

Although the IAT is accessible through a link that can be freely distributed to anybody, our ethics approval exclusively covered data collected from members of the College community. Interviews took place on College premises, with informed consent obtained in advance. Interviews were recorded using a laptop computer and a mobile phone app, uploaded, stored on a password-protected server in accordance with ethics protocols and subsequently deleted from the laptop and mobile phone. Transcribed interviews were then anonymized to remove all identifying features.

Results: A case of decolonial enquiry and resistance

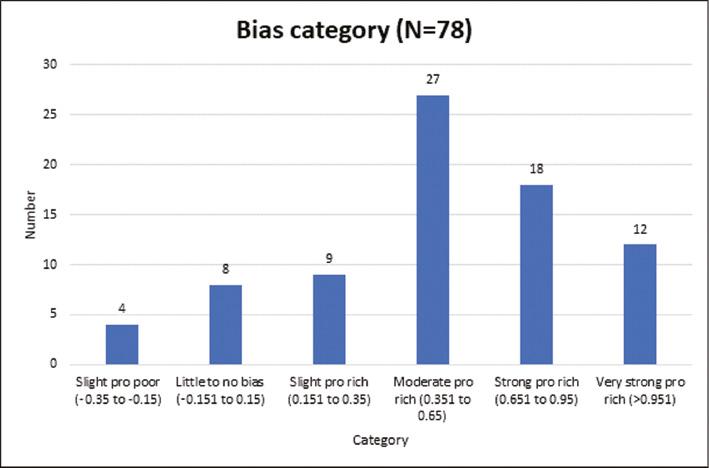

The reading list analysis provided the geographic origin of 676 assigned items for the 2017/18 Master’s in Public Health programme. Overall, 97.8 per cent of first authors and 96.4 per cent of last authors were affiliated with institutions based in high-income countries, compared to 1.2 per cent, 0.3 per cent and 0.6 per cent for first authors, and 1.9 per cent, 0.4 per cent and 0.5 per cent for last authors for upper-middle income countries, lower-middle income countries and low-income countries, respectively (using World Bank categories). Figure 1 depicts a cartogram of the relative geographic distribution of readings assigned on the reading list and the countries’ Gross National Income/capita. Descriptive reports of findings from the reading list analysis were sent to module leaders and, over the subsequent few days, this elicited a wide variety of reactions, with many suggesting that the analysis had made them more aware of the geographic distribution of the readings and that it had stimulated some discussion around whether modifications could be made in the future.

Cartogram depicting the relative distributions of citations on the 2017/18 Master’s in Public Health course (larger size of country represents higher number of citations; darker shade of country represents higher income status based on gross domestic product (GDP)) (Source: Authors, 2021).

The major themes that were identified through interview analysis included the positive changes that have occurred at our institution over the years, how our work resonated with participants and made them reflect on their work, and practical barriers that make decolonizing and including more diverse sources in the curriculum a challenge. A theme also emerged which describes deeply entrenched cognitive barriers that may lead to defensive reactions and constitute major challenges to advancing decolonization work. Each of these are discussed in turn below.

Positive changes and reactions

As discussed above, the College has taken several actions in recent months to address calls to decolonize. Another initiative has been the Learning and Teaching Strategy (Imperial College London, 2017), which has prompted educators to think about what they can do to make their programmes more inclusive, as explained by this participant:

People have become much more interested in these issues, it’s kind of, much more, sort of, ‘acceptable’, it’s much more embedded in the Learning and Teaching Strategy …

It’s something to kind of … point to, it’s something tangible that you can say to people, ‘Here is a thing and it says that we should be doing X.’ (Participant 1)

For some, it has provided the ‘language’ that enables them to engage with educational reform:

I’ve seen that people are more receptive to some of these ideas, or people will say, ‘Oh, I’ve been thinking about these things for a long time, but I’ve just never had the language’, or ‘I didn’t know it was a thing’, or whatever. (Participant 1)

For many participants, our faculty workshops have been an opportunity to consider how geographies are represented in curricula, and the structures that perhaps perpetuate such representations. Two participants, one from the Central Library and one from the Faculty of Medicine, shared how they intended to apply new understanding to their professional lives:

But [the workshop] made me go away thinking, specifically for my work … would there be a purpose to looking more closely at the work that I do. And I think, looking on a really surface level, the information literacy frameworks I’m aware of are all developed in Western countries. (Participant 2)

I hadn’t really thought previously about looking at our departmental work in this way … What your work showed, and what we know, is that medical research is not free of subconscious bias … I’m really lucky, I work in a very progressive department … and there are a number of us in our department that have a real interest in this and feel committed to wanting to engage with this further … This is educationally sound that we address this, this is not just a case of equity. (Participant 3)

Practical barriers to diversifying the curriculum

Although overall the reactions from workshop and interview participants indicated a sustained engagement, barriers were also discussed. Some mentioned a lack of time or a need for space to think harder about the aspects of their STEMM curricula to which this is relevant:

So, in the relative scheme of taught courses within Imperial, undergraduate first and second year [physics] doesn’t lend itself to the possibility of the sort of geographic bias you were referring to in that [workshop] as much as some others. But there are some aspects of it … because of the timing of when [the workshop] was, and the teaching I’ve done since, I literally haven’t had a chance to implement anything. (Participant 4)

Discussion of representativeness relies on module leaders, as subject matter experts, to decide whether any skew in geographic representation of readings is expected, surprising or even problematic. However, lack of access to research from different disciplines may also simply be due to administrative barriers:

We have a collection development policy, … and that choice to not have access to [social science] materials isn’t necessarily the manifestation of any kind of bias, other than, like, these disciplines – let’s just say, anthropology, or, let’s just say, sociology – are not departments here. (Participant 2)

This participant also explained that through the institution’s membership of the Society of College, National and University Libraries (SCONUL), there is a way to gain access to resources that are not in the Central Library’s permanent collection. As educators ourselves, we have often been warmly encouraged by librarians to suggest and request acquisitions in fields such as anthropology. Yet, even though advances in curricula to involve viewpoints from a diversity of disciplines, and perhaps therefore from a diversity of geographies, have been made, actually doing so may be hindered by the simple fact that the library holdings of a STEMM-focused institution do not always allow for a quick and more large-scale inclusion of such literatures.

The presentation of reading lists as cartograms and as descriptive statistics representing the geographic origin of the authors of citations on the lists was an approach supported by some faculty members, in part because where a literature is from is not immediately apparent from the citation sources on a reading list. There was a sense that being conscious of the geographic location of authors is not a particularly common occurrence, and signalling this could promote important awareness:

I thought, ‘my awareness of where the research has come from is woefully inadequate.’ I don’t know, often. When I thought about it, I thought most of it comes from the typical UK, US, few European institutions, so it’s very traditional in that sense. (Participant 5)

I’ve not at all in this past year even been conscious of the geographical location of authors or who my authors are, or indeed where they come from, and, again, I think that’s what a lot of your response is going to be like. You know, ‘I put this because it’s good content, period.’ (Participant 6)

It would require conducting systematic reviews on every taught topic to ensure that reading lists are representative, which is clearly impractical, and so module leaders, as subject matter experts, are an integral part of the diversification of reading lists for the purposes of decolonization, whether they are aware of the research landscape or not. By pointing out the geographic diversity of teaching materials, and by relying on their expertise to interpret it, course reading lists may ultimately become more representative of the global research landscape.

There are also organizational barriers noted in the interview data. As is likely to be the case in any large institution, organizational inertia can impede change, irrespective of any bias or prejudice against the changes being proposed. For example, despite some noteworthy initiatives outlined above, some management styles can be perceived to favour the status quo:

Now, I think quite a lot of the management style at Imperial … is not so progressive, but sort of just maintaining the status quo … I don’t think there’s any proactive engagement to kind of really facilitate and change or progress. And that’s, regardless of the context around that, that’s kind of the response … the majority of people are just upset [because] they’ve been asked to change, as opposed to [having] any real hostility towards the changes themselves. (Participant 6)

Furthermore, whereas some university actors, such as librarians, are potentially well-placed to offer insights into reading list characteristics, speaking up to help incorporate more geographically diverse reading materials is not yet perceived to be a safe space for their involvement. When asked if they could see themselves influencing reading lists, a librarian replied:

Perhaps … I hesitate to say ‘yes’ … To open the door to there would ever be a scenario where you’re going to be sitting down with an academic and be discussing the content of their reading list with them – that’s just, like, so daunting. (Participant 2)

Beyond organizational inertia, and entrenched roles across the institution, we found also that there are significant cognitive barriers that must also be addressed.

Cognitive barriers: A case of epistemic fragility?

Although we do not know the reasons for it, our initiative led to a complaint that was escalated to senior faculty, and we were requested to retract the work, submit an apology and justify the purpose of the reading list analysis. Our project was about introducing ideas and conversations that normally occur in the realm of social science into a STEMM context. This required an understanding that access may not be equal between groups, that there may be an imbalance of power, that members of certain sociodemographic groups may be privileged and that unconscious bias may exist. This may, however, sit at odds with the natural sciences for several reasons. We classified these central tensions that exist within the minds of academics in the STEMM field and the principles of the decolonization movement as ‘cognitive barriers’, which were an impediment to the goal of our project. One participant explained their experience with discussing social sciences at Imperial College:

When I first started teaching [at Imperial], [social science] was totally alien to people, people were like, ‘what are you talking about?’ Or, people were quite antagonistic against it, there was almost a sense of, ‘we’re scientists, we deal in objective facts, we’re not biased, we deal in merit. If somebody is good enough to become a professor, then they’ll become a professor’, sort of thing. (Participant 1)

Conversations around representativeness invoke discussion of unconscious bias and privilege. Although the reading list analysis cannot prove, on its own, whether a particular gaze, unintentional or otherwise, is occurring, it requires consideration of this possibility, and thereby places the educator in a reflexive position which, for some, might be outside of a comfort zone:

The risk is that people will turn around and say, ‘Well of course I’m not biased, I’m very objective, I’m a scientist, science is very objective, you know, we don’t deal with bias, and in any case, it doesn’t really – that’s not what we are about teaching in the medical field.’ (Participant 3)

One aim of the decolonizing movement is to challenge hegemony in the higher education setting. This means ensuring that knowledge created in LMIC settings is considered equally to knowledge and research originating from HICs, and not prematurely discounting it or being prejudiced against it. Some of our interview participants pointed out that this is still a deeply entrenched issue:

In my mind, so many of the health practices or understanding of health in [an African] way, from where I’m from, is just, they are not – they are almost automatically considered unimportant or not worthy. It’s very difficult to shake that assertion that a lot of people make, that it is superior, it is better, it is of a higher quality if it is Western, if it is white, if that is where you’ve derived your knowledge from. (Participant 6)

Sometimes we try and think about using examples that are really similar to Imperial, because that will be acceptable to people. (Participant 1)

Several interviewees further elaborated that reading lists can be categorized as having formal and informal elements, and it is far simpler to make changes to the informal ones (such as reading for homework assignments), whereas there was discomfort in challenging or changing core texts:

I think amongst some staff, there might be a sense of, ‘Oh, but if you start putting in this research from a low-income country, you are overshadowing the stuff we really need to know’, like, the absolute basics. (Participant 5)

The idea that the ‘absolute basics’, or what students ‘really need to know’, could be ‘overshadowed’ or diluted if research from LMICs is included suggests entrenched beliefs about the relative importance of different knowledges. This highlights a key barrier to geographic representation, as content still competes for inclusion in often over-full STEMM curricula. Despite positive comments regarding the importance of this initiative in raising awareness about lack of representativeness, interviewees also highlighted the sensitivities around the messaging and an unintended impact of the reading list analysis:

I could understand that people could easily feel quite threatened by thinking ‘Oh, you’re saying I have unconscious bias, are you calling me a racist?’ (Participant 3)

It’s taken as criticism, and there’s a feeling that this idea that it’s audited is quite, you know, invasive and critical. (Participant 6)

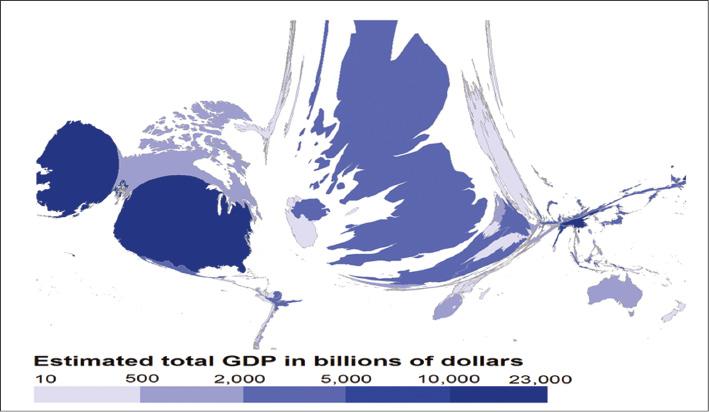

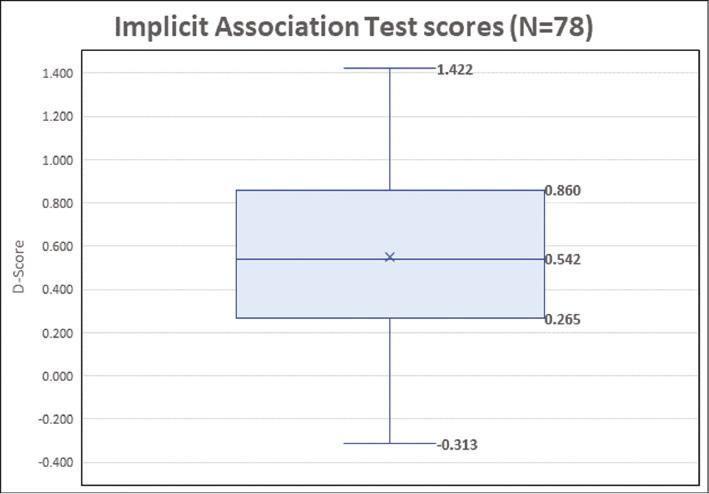

We end our results section with the findings from our IAT (Figures 2 and 3). For the 201 College members who have completed the test, 78 were faculty, 75 were students, 13 worked in administration and 35 worked in other departments. The median D-Score (the measure of unconscious bias) for just the faculty respondents was 0.542 (95 per cent CI –0.211; 1.315), suggesting a ‘moderate’ unconscious association between high-income countries and ‘good research’, and low-income countries and ‘bad research’, with 73.08 per cent of respondents exhibiting either a ‘moderate’, ‘strong’ or ‘very strong’ pro-HIC bias, suggesting, if nothing else, that there is scope for further enquiry to understand whether choices made in developing teaching material are indeed based purely on merit.

Implicit association test scores showing the distribution of results across 78 faculty respondents. D-scores represent the associations between the categories ‘high-income country/low-income country’ and ‘good research/bad research’. A D-score of 0 represents no implicit association between categories (Source: Authors, 2021).

Discussion

Although the practical barriers were indeed insightful, we focus our discussion on the salient issues of cognitive barriers in decolonization initiatives. It may not have been the most common theme, but we find it to be the most interesting because it represents a dissonance between what we expected and the reactions we received.

In so far as diversity and inclusion of marginalized groups are important, so is the inclusion of marginalized epistemologies and knowledges. However, we are disciplined by our disciplines, and the extent to which these constrain the geographies from where we source our learning and teaching becomes important. Different cultures from different geographies have different sciences, technologies, ways of knowing and conceptions of what qualifies as knowledge (Andreotti et al., 2011; Cetina, 2007). As some suggest, rather than erasing differences through ‘gender-blind’ or ‘colour-blind’ policies and practices, it would be more beneficial to embrace differences and previously marginalized epistemologies, to thus grapple with the ‘messiness of difference’, and advance through the discomfort that this may produce for some (Paton et al., 2020). While it may not improve a particular discipline, it would seem that diversity of geography and perspective on a curriculum would nonetheless be of value, regardless of the discipline that is being taught.

We had assumed that presenting the reading list data would at best be used to stimulate debate, and at worst be ignored. However, this perspective presupposed an awareness of debates around privilege and decolonization that perhaps was overestimated, in the sense that these values might not be equally shared. It also presupposed that such a representation was neutral, which, as it turned out, was not the case. It has been a learning opportunity for us, and therefore may also be for others engaged in this process, not least because there is a general lack of empirical experience. There are parallels with other similar debates, particularly in the realm of social, rather than cognitive, justice, broadly analogous to the fragility responses described in detail by DiAngelo (2011). We cannot categorically state that our work elicited fragility reactions, because the unfolding events did not offer us the opportunity to explore these reactions in detail. However, based on some of the interviewees’ responses, the intervention seemed, to us at least, to be about an effortful reinstatement of a status quo that had been challenged through our reading list analysis.

Advancing DiAngelo’s (2011) ideas into the academic realm, our reading list analysis was asking academics to consider whether the distribution reflects systemic (individual, institutional or societal) barriers to publication of research from LMICs. The interview quotations selected above reflected as much. So, to ‘authority’, we were asking whether the reading list distribution reflects that the West is indeed best, and who gets to decide? Our respondents considered that health practices and knowledge derived from ‘Western’ and ‘white’ sources may be considered ‘superior’. To ‘individualism’, we were asking whether the reading list distribution invites discussion of alternative ways of knowing and teaching, and we found that if literature from LMICs is included on the reading list, this might detract from ‘the absolute basics’. To ‘objectivity’, we were asking whether the reading list distribution reflects how heuristics play a part in choosing certain literatures over others, and we found that as the idea of objectivity is central to scientists in the STEMM field, it is anathema to suggest that materials might be selected based on anything other than merit. To ‘centrality’, we were asking whether the reading list distribution invites a more global, equitable knowledge base, and we found a tendency for educators to use examples that arise from a similar context to the College as more ‘acceptable’ practice. Using DiAngelo’s (2011) terminology, the stress created by our reading list analysis may therefore have led to a swift negation of the results by some, perhaps to reinstate, effortfully, a perceived epistemic status quo. This was observed with a range of defensive moves, such as an escalated complaint, but also, as suggested by the interviewees, that inclusion of alternative knowledge sources will overshadow what is really needed and that, as scientists, our work is not confounded by subjectivity or individual unconscious bias.

In another sense, the epistemic fragility we describe may have had little to do with reactions to the characteristics of included articles in reading lists and more to do with the epistemological basis to the line of enquiry itself. The decolonization debate has predominantly been carried out at institutions with a social science focus, and it is only slowly entering the realm of physical, natural and medical sciences (Gishen and Lokugamage, 2018; Lokugamage et al., 2020). Our choices to use reading list analyses and the IAT were an effort to frame unfamiliar topics (in this case, decolonization) with familiar ones (quantitative methods) to make them more palatable for the intended audience. The combination of a positivist and an interpretivist research tradition might be considered a benefit. However, it also posed a unique challenge: can the process of decolonization really be ‘quantified’? As such, the question arises whether the fragility reactions we observed are a response to epistemic practices found in the STEMM disciplines (such as meritocracy, objectivity, authority and individuality) or a response to challenges to the very epistemic foundations of the STEMM disciplines (such as true/false statements, rationality and neutrality).

As shown in the interview quotations, in STEMM subjects in particular, bias is understood as something that is addressed in the study design phase and can therefore be disregarded or controlled for. The science speaks for itself, and it is understood to be objective and free from emotions, private interests, bias or prejudice (Gieryn, 1983). This has, on the one hand, allowed natural scientists to isolate and protect the autonomy of their field, claiming that scientific research is free from any sort of interference (Gieryn, 1983). It can also influence the culture and language of STEMM in a way that can hamper conversations about decolonization, which necessarily involve examining the subjective and working with inevitable bias. It is in this manner that decolonial movements might fragilize STEMM epistemologies. On the other hand, it has also enabled the creation of a clear boundary between the intellectual authority of natural science and the subsequent denial of all other forms of enquiry as ‘pseudoscience’ (Gieryn, 1983). Given that our subjectivist line of enquiry – typical of the social sciences – was being applied to a public health course led by some of the world’s leading epidemiologists and natural scientists, it could perhaps have been anticipated that our analysis would be questioned by a ‘knowledge elite’ (Antoniades, 2003; Gieryn, 1983), with their usual practices firmly rooted in the positivist traditions. Although our data might suggest a possible fragility among those working in the positivist STEMM traditions when confronted with subjectivist approaches, we hesitate to draw this conclusion definitively. We cannot exclude the possibility that the inverse – fragility among social scientists when confronted with positivist approaches – might also occur. Ultimately, it is not our intention to conclude that one epistemology is superior to the other, as this would only serve to perpetuate issues associated with hierarchies of knowledge. Rather, as we argue above regarding diversity and inclusion of perspective and geography, we wish to suggest that there is also value in embracing differences of thought and epistemology in one’s research practices.

We offer, from this experience, that this epistemic (not white) fragility occurs when modes of enquiry do not fit the mould established by modern knowledge, and when they are therefore not considered ‘real’ knowledge (Andreotti et al., 2011). At best, they are beliefs, opinions or subjective understandings (Andreotti et al., 2011). However, these dominant ‘logics of enquiry’ (epistemologies, ontologies and axiologies) are social products, and they can exclude the social histories and epistemologies of other social groups (Scheurich and Young, 1997). Epistemic fragility provides a perverse pressure against change and a need to go outside our comfort zone. While we might say that there is general agreement on the need to decolonize education, that is not enough to prevent the emotional side associated with transformative learning being uncomfortably exposed (Mezirow, 2009). Calling attention to, and redressing, these colonial legacies and the inequalities they perpetuate is at the heart of the decolonial movement.

There are several limitations to our case study. We interviewed participants from different faculties within the College, providing a diversity of viewpoints and experiences (Palinkas et al., 2015). However, these were a doubly self-selecting sample, having first voluntarily agreed to attend the workshop and then offering their time to be interviewed, therefore inferences to the broader faculty community should be made with caution (Battaglia, 2008). Although IATs are a valuable tool to study the relative strengths of implicit associations, and have been shown to have strong internal validity (Nosek et al., 2007: 280), an individual’s unconscious bias might not manifest explicitly, and the tests do not, on their own, lead to institutional change.

Despite the merits of a data-driven approach, reading list analyses, being descriptive, cannot determine whether any geographic skew is due to unconscious bias in the selection of that material or whether it reflects broader global patterns of research production and dissemination (Grimes and Schultz, 2002). There could be several explanations for any skew, not least that knowledge production and publication is heavily weighted toward Western Europe and North America (Bornmann et al., 2011; Cooper et al., 2018; Pan et al., 2012), and reading lists may simply reflect that broader issue. For some subject areas, the suggestion to include more research from LMICs may therefore be limited due to there being few suitable sources to include. Similarly, although we claim that our data-driven approach is objective and shows ‘just the facts’, there is nothing inherently objective about our method. Statistics, like qualitative data, can be biased (Gillborn et al., 2018). In our case, the decision to look at geographic diversity, rather than, for instance, gender diversity or disciplinary diversity, reflects both our agenda, and perhaps also our own biases, perhaps reinforced from our previous research findings.

Although we identify the lack of research and knowledge production from LMICs as a ‘practical’ barrier, this betrays the reality of the issue. Indeed, the barrier is very likely of a systemic nature, resulting from a lack of resources, which itself can be traced back to geopolitical factors and a ‘colonial matrix of power’ that upholds and reproduces the Western ‘modern’ construction of knowledge and power (Quijano, 2000). Not only might this lack of resources preclude scientists from carrying out research, but it might also prevent them from paying the substantial fees to have their research published in highly visible journals – which are often also based in HICs. It is evident, therefore, that for consumers of knowledge, lack of available research may be a ‘practical’ barrier, but for producers of knowledge, the odds are stacked in favour of researchers in HICs.

Our analysis of institutional affiliation in each citation sheds little light on the individual identities and trajectories that authors of those articles may have taken. Our initiative, while certainly aimed at promoting voices that had previously been excluded from the curriculum, did not entail, or require, module leaders to perform any of the more fundamental or central decolonial activities. This may be our failing, and it could be argued, even, that asking our colleagues to simply perform the ‘tick-box exercise’ (Hall et al., 2020) of tokenistically including additional research from LMICs decidedly does not represent a decolonization of the curriculum.

Finally, DiAngelo’s (2011) work is not without its limitations and criticisms (Applebaum, 2017; Thomas, 2020). Some argue that framing whiteness as ‘fragile’ in effect buttresses the invulnerability of whiteness, and thereby allows white people to ignore and disregard aspects of existence that might be unsettling or inconvenient to them (Applebaum, 2017). There is also the risk that the perspective of a white woman (DiAngelo) on this topic is once again given precedence over the myriad voices of people of colour (James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, Paulo Freire and Angela Davis, to name a few), who have been illustrating white fragility for years, decades and even centuries (Thomas, 2020). We were less concerned with the racial component than we were with the fragility reactions, and which underlying assumptions and world views might have been challenged to elicit these reactions. We have not been the only ones who have made this connection (Hartland and Larkai, 2020).

Concurrently, we sought to navigate the debate away from race issues, focusing instead on the geographic origins of research, which we felt would be more neutral. Yet, decolonization and anti-racism go hand in hand and are two sides of the same coin. Indeed, the parallels between our epistemic fragility and DiAngelo’s (2011) white fragility are likely no coincidence and instead serve to illustrate the many notable intersections between the two concepts. There are significant systemic barriers to entry to academia, and thereby also to epistemic communities; consequently, the arbiters of what is deemed and valued as knowledge can become skewed. Beyond the parallels with fragility responses, is there a relationship between epistemic and white fragility? Whiteness is not defined by skin colour alone, but is instead a ‘set of locations that are historically, politically and culturally produced, and which are intrinsically linked to dynamic relations of domination’ (DiAngelo, 2011: 56). Western universities are one of these locations, as they serve not only to reproduce status, but also to preserve and legitimate meritocracy (Warikoo and Fuhr, 2014). However, where DiAngelo’s (2011) concept applies to the reactions predominantly of white people, ours does not. Epistemic fragility reactions can occur in anyone who subscribes to the idea that a hierarchy of knowledge exists. Likewise, they can occur in those who believe that the principles and methods of STEMM are inherently objective, when it has been argued and shown that they are not (Gillborn et al., 2018). Just as we can – and must – accommodate and strive for diversity of people in all aspects of our daily life, we can – and must – accommodate and strive for diversity of knowledge in academia as well.

We have been cautious not to consider our work in binary terms – success or failure – but to recognize that there are lessons for all interested in decolonization initiatives in STEMM institutions. We have learnt that it is helpful to anticipate strong, emotive responses from some educators when engaging in this debate. Work by Kinchin and Winstone on pedagogic frailty (Kinchin et al., 2016) connected to professional autonomy resonates with our observations and will be useful for developing workshops and guidance that acknowledges the competing pressures felt by staff who teach in universities. Similarly, Felman (1992), Boler (1999) and, more recently, Ippolito and Pazio (2019) suggest that ‘discomfort’ can play an important role in pedagogy and social transformation and that therefore strong reactions should be engaged with, rather than dismissed as the result of ‘fragility’. Gilson (2014) further advances this idea to describe epistemic vulnerability to challenge one’s ideas and beliefs, along with embracing a willingness to change oneself (Gilson, 2014).

When managing the process of decolonization change, attention must be paid to power within academic networks, and how this is wielded to negate ways of knowing that do not fit within the dominant episteme. For those engaging in this area, fragility responses should be expected and prepared for, but change, when it eventually happens, is worth the wait. Following on from their participation in one of our workshops, we have been collaborating with Central Library staff to scale the bibliometric analysis of reading lists to other programmes and faculties. This will allow a broader range of module leaders to use their reading list data to drive educational transformation where appropriate to do so. Through this collaboration, we have also been able to address the key limitation of focusing only on first and last author. Instead, we can now collect information for all authors associated with a citation (Price et al., 2021). Our workshop has also become a biannual fixture in the Educational Development Unit’s calendar of workshops.

Conclusion

Promoting scholarship from LMICs is just one of the key activities necessary to challenge how and what we identify and qualify as knowledge, and which ideas are worth sharing (Cooper et al., 2018). Any efforts towards decolonization must include an interrogation of how the university has played a role as a modern colonial instrument, reinforcing Western perspectives at the expense of knowledges from elsewhere (University of Amsterdam, 2016). Educators engaging in a decolonization process would do well to consider how best to manage this change process and to expect and be prepared for fragility reactions when they occur. It is a necessary stage of change. These reactions might be interpreted as positive in a sense, because they demonstrate that participants are emotionally engaged in their work. We propose epistemic fragility, with its focus on meritocracy, individualism, centrality, objectivity and authority, as a framework to understand the reactions related to efforts to decolonize higher education. Future research should seek to build on this framework, validate it in other settings and other disciplines and explore the nexus between geography, gender and race.