Introduction

During a breaktime conversation, two Year 7 students were excited to share with me (CN) that they had produced a podcast that centred on issues of race and racism. After a series of questions ensued about online safety and the practicalities of the project, I reflected on how the actions by these students indicated a profoundly different outcome resulting from my attempts to decolonise a series of geography lessons. These students had begun to apply the concepts of race and inequality to create a platform both to further their own learning and to address the continued marginalisation of Black voices. In the students’ own words: ‘We hadn’t learnt about colonialism, as you said [referring to CN], it doesn’t appear in the curriculum. So, when we started covering topics such as the Bristol Bus Boycott, we were really excited to link our knowledge.’

These students thus demonstrate a practical engagement with anti-racism. Indeed, it is an engagement which stems from a level of personal confidence and adeptness with technology, but we want to argue here that it is also enabled by what Healy and Mulcahy (2021) called an ‘affirming ethics’. For these authors, curriculum and pedagogy ‘invites an ethics of affirmation that augments the affective capacities of learner- and teacher-bodies, enlarging their potential to engage in ethical action’ (Healy and Mulcahy, 2021: 1). When applied to decolonising the curriculum, we argue that this focus on student agency is an important supplement to approaches to decolonising curricula. According to Morreira et al. (2020b: 137), enabling student agency is a decolonial practice, as it ‘allows for the creation and maintenance of students as embodied, knowledge-making persons situated within communities, rather than as abstracted individuals to whom academia imparts knowledge created by others’.

As two geography educators – one teaching in a London secondary school (CN) and the other being the director of a university-based geography initial teacher education programme (ER) – we want to use this opportunity to reflect on how decolonising can be approached by both teachers and teacher educators. We see common themes between decolonising in higher and secondary education, such that we feel it is important to talk across these two contexts. Here we define decolonising as the set of heterogeneous pedagogical practices that bring to the fore the effects of colonisation and its consequences, such as forced migration, occupation and subjugation of Indigenous people, in a manner that interrupts ‘the dominant power/knowledge matrix in educational practices’ (Morreira et al., 2020a: 2). The pedagogical means through which these ends are achieved by educators are diverse. We therefore begin this article with an attempt to map some of the approaches to decolonising deployed by geography teachers in UK secondary schools.

This analysis then draws on two case studies, one from a series of lessons in a Year 7 geography classroom, the other a (virtual) decolonising walking tour of central London for geography teachers completing their Postgraduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) course. This allows for reflection on the ways that decolonising might be adapted for different educational contexts. Both case studies foreground two distinct methods for promoting the agency of students. This first is to develop students’ relational thinking – where they appreciate the geographical connections and traces that connect the UK to other parts of the world in the past and present. Building on ideas suggested by Morreira et al. (2020b) about the importance of place in decolonial efforts, the second method shows how a practical and embodied experience of a city helps students to reflect on the effects of colonialism.

Both these case studies contribute to the growing body of educational scholarship on practical methodologies for decolonising curricula (for example, Luckett et al., 2021; Liyanage, 2020; Le Grange, 2016). These two case studies are not templates to replicate – indeed, the strength of decolonial practices lies in their heterogeneity – but provocations that we hope inspire educators to think about how decolonising curricula can apply in various educational contexts and across various disciplines.

Approaches to decolonising the curriculum in geography education

In geography education, there is an increasing recognition of the way curriculum knowledge creates and perpetuates particular ways of seeing and acting in the world that remain ‘deeply rooted in post-Enlightenment Euro-American claims to be able to pronounce universal truths and to theorize the world’ (Radcliffe, 2017: 329). The construction of the curriculum is therefore inherently political. For geographers, this is particularly problematic as the disciplinary history of the school geography curriculum is bound up with the project of empire (RGS, n.d.a; Kearns, 2009).

Colonial legacies are still present in what is taught in the geography classroom, and in who is given the right to produce and disseminate geographical knowledge. Puttick and Murrey (2020) highlighted how the word ‘race’ does not appear once in the Department for Education’s Key Stage 3 Geography Programme of Study or GCSE subject content, and A level subject content is similarly silent on this issue. More broadly, scholars have considered how the British education system can actively serve to create and reinforce racial and class-based inequalities (Kulz, 2017). Similarly, in higher education, Rose (2020: 138) noted that in 2019 ‘there were 21,000 professors in UK universities and only 140 of those 21,000 professors identified as black (and of those, only 25 identified as female)’.

The murder of George Floyd catalysed a renewed impetus among geographical educators to do more to reflect on and address the silence of race in school curricula. Much of this work has been driven by efforts of individual geography teachers and academics. Individual teachers have shared their thinking and approach to the development of anti-racist geography curricula on Twitter (for example, ‘Anti-racist Geography Curriculum’, https://twitter.com/ARGeogCurric), blog posts (for example, Rackley, 2020) and via short, informal presentations at TeachMeets. Examples of geography teachers’ practical efforts to decolonise curricula are numerous. For example, Robinson (2020) – a UK-based geography teacher – blogged about how she has used websites such as Dollar Street to counter generalised and stereotyped representations of Africa.

Table 1 summarises what we suggest are three current approaches to decolonising geography curricula. This has been derived from a summary of social media posts on Twitter, as much of the work of decolonising curricula currently exists in the format of online discussions and informal conversations among educators.

Table 1 shows three main approaches to decolonising curriculum content. Approach 1 is distinguished by a focus on addressing ‘misconceptions’, such as about the cultural–economic–environmental homogeneity of Africa. Approach 2 is distinguished by encouraging students to think critically about the dominance of discourses within geography and the contemporary political discourse. For example, Robinson (2020) spotlighted how in her teaching she foregrounds the idea that the United Nations Millennium Development Goals perpetuated African countries’ dependence on the ‘West’ as an example of neocolonial relations (see also Durokifa and Ijeoma, 2018). This approach foregrounds how not only single lessons, but also schemes of work might be built around postcolonial approaches that encourage students to think critically about uneven power relations that continue to perpetuate inequalities and dependencies. Approach 3 can be distinguished by its incorporation of Black histories that have been hitherto marginalised from curricula. For example, the Windrush Foundation (https://windrushfoundation.com/about-us/) is a UK-based charity that has created geographical schemes of work that ‘highlight African and Caribbean peoples’ contributions to UK public services, the Arts, commerce, and other areas of socio-economic and cultural life in Britain and the Commonwealth’. This approach is characterised by its affirmative ‘curriculum-making’ – reforming curricula to include the perspectives of those who have been marginalised.

We suggest that each approach is oriented by a different ‘pedagogical imperative’. Approach 1 is characterised by a focus on correcting knowledge, Approach 2 is characterised by critical, postcolonial orientation that identifies power structures and inequalities, and Approach 3 seeks to rebuild curricula in a way that foregrounds the experiences of hitherto marginalised people, including the lived experiences of students themselves, in a manner that promotes student agency. Together, these approaches help to parse the catch-all term ‘decolonising’ in reference to geographical curricula. In practice, the school curriculum is likely to shuttle between these different approaches, and there may well be aspects of these different approaches within a single lesson or scheme of work. Moreover, they emphasise our understanding that discussions around decolonising the curriculum, in terms of what is in the curriculum, are inseparable from discussions around the pedagogies through which the curriculum is enacted.

Case studies and approach

The empirical material presented here centres on a scheme of work developed for a Year 7 geography class in a secondary school in London, UK (September–October 2020), and an extended ‘subject session’ delivered over the course of an afternoon as part of a PGCE geography programme for trainee teachers at King’s College London (February 2021). The series of lessons delivered to the Year 7 class were part of a broader scheme of work on globalisation that was adapted to focus on aspects of globalisation that relate to the British Empire, the slave trade and the ways that these relations have a contemporary legacy in modern Britain.

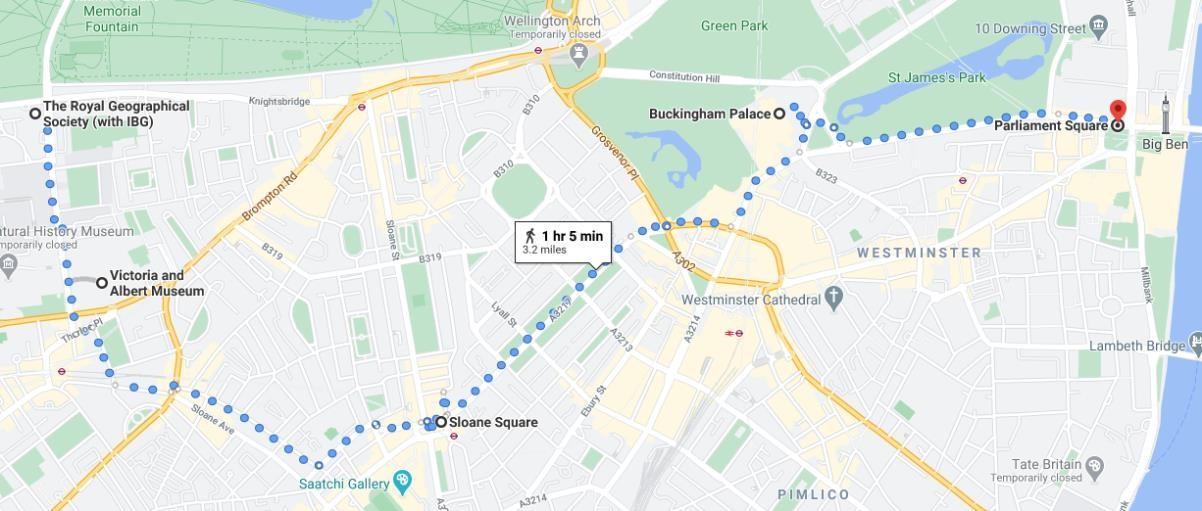

For the PGCE course, the subject session was delivered through a walking tour of London which, due to COVID-19 restrictions, was led ‘in the field’ by CN, with ER and the student group joining remotely via Microsoft Teams. The name and objectives of the tour were inspired by an ‘Uncomfortable Oxford’ walking tour, whose website describes it as ‘dedicated to raising awareness about the “uncomfortable” aspects of history and their impact today: racial inequality, gender and class discrimination, and legacies of empire’ (https://www.uncomfortableoxford.co.uk). Our walking tour lasted approximately three hours, and it was deliberately planned to encompass the key sites in London in which the remnants of empire and current debates are most overt. The tour began in South Kensington, which Gilbert and Driver (2000: 28) argued is the place where ‘the connection between empire and the collection of knowledge was at its most explicit’. It encompassed five main stops: the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), the Victoria and Albert Museum and Natural History Museum, Sloane Square, Buckingham Palace and Parliament Square (Figure 1).

Each stop facilitated the opportunity to discuss a different dimension of empire and colonialism. For example, the RGS was used to prompt discussions about the ways that many school trips continue to be motivated by ideas of exploration and travelling to ‘distant’ places, and Buckingham Palace was used to reflect on the Victoria Memorial and the interconnections between Africa and Europe. The key stops on the walking tour, and the corresponding dimensions of colonialism that were discussed at each stop, are listed in Table 2. Trainee teachers used a Google Jamboard to record their thoughts at and between particular sites, with an emphasis on thinking through how the walking tour might be incorporated into the geography curriculum. Our hope was that the walking tour would not only foreground colonialism in London, but also equip teachers with the confidence to translate aspects of the pedagogy and ideas into their own classrooms.

Both the Year 7 lessons and the walking tour took place in London. Gilbert and Driver (2000: 23–4) argued that ‘London was not merely the political and financial capital of a global empire: it was also a place where the empire could be seen and experienced’. These authors reminded us that different parts of London (the Tube, Westminster, Oxford Street and so on) engineer different dimensions of ‘imperial experience’ that ‘helped to shape the British sense of themselves, as a nation and as a people’ (Gilbert and Driver, 2000: 24). The urgency to critically interrogate London’s colonial past–present is a pressing and almost limitless project. Rather than operating in a more abstract realm of theory, our idea of the walking tour was to enable students to develop a sense of the material ways in which power and inequality are fashioned through the spaces of the capital. The virtual nature of the tour meant that undoubtedly it was much harder for students to sense these relations, such that our preference would have been to conduct the tour in person.

While the methodologies explored here might be most easily transferable to other urban contexts in the UK and Europe, we suggest that there is no single methodology for decolonising curricula. Indeed, it is important that educators take into account local contexts and individual schools and classes when thinking about how to make decolonising meaningful in different settings. For example, an ‘uncomfortable walking tour’ may well be developed for secondary school-aged children, and decolonising a scheme of work can be applied to university degree courses. Our approach is one that sees decolonising as more than an intellectual exercise; it is a process of educating that has the potential to make new, more socially just worlds through enhancing student agency. This is a position that resonates closely with a broader shift in approaches to education. For example, education for environmental sustainability has recently focused on practical methodologies that support students to amplify their voices in the process of creating more environmentally sustainable futures (Dunlop and Rushton, 2021; Rushton and Batchelder, 2020).

Both case studies take place in educational settings that give sufficient scope for pedagogical innovation and educator autonomy and freedom. We recognise that this is not the case at all in secondary and tertiary institutions. Indeed, there may be barriers to implementation, such as the time and space required to put together new programmes of study, and there may even be reluctance or apathy from school and university management to allow this work to take place. It may be that school curricula are planned and managed centrally in a way that ensures consistency across lessons, but that potentially comes at the expense of allowing individual teachers licence for curriculum experimentation.

In both our case studies, learners were already sensitive to issues of racial injustice. We recognise that the cases we present are emergent from, and enabled by, the contexts in which we teach. However, this is not to say that this work is complete, nor as ‘unsettling’ as it might have been. The affective dimension of this work had to be carefully calibrated in a manner that negotiated the expectations of the curriculum between students, teachers and parents, while continuing to challenge established discourses.

By its very nature, the work of decolonising is to unsettle dominant narratives, disrupt taken-for-granted ways of seeing and replace ‘comfortable’ narratives about British identity and history. Within the secondary school context, this generated conversations with department colleagues around what might be ‘too shocking’ to teach to particular year groups. This raises interesting questions about not only the expectation of shock and surprise in the classroom, and how to prepare students for this, but also how these affective dimensions of decolonial teaching might be planned for through different year groups as a form of progression.

By spotlighting these two cases, we acknowledge that this article is a modest contribution, but nonetheless we hope that it serves as the start of much more substantial practical, creative projects that address colonialism within geography education. Neither of us would consider ourselves as ‘experts’ in colonial and postcolonial geographies and/or theory. We approach this work through our own heterogeneous backgrounds and professional identities, and work with an ethic of ‘decolonising solidarity’. This recognises that decolonising is a ‘path towards a transformative learning gained through a social movement learning in which we each continually commit to a willingness to learn, to listen and to become’ (Kluttz et al., 2020: 64). In other words, decolonising is more than simply ‘allyship’, and it must be more than an academic exercise. It must be a process in which we, as educators, learn and are transformed.

It is thus important that all educators reflect carefully on what it means to ‘decolonise curricula well’. For Kluttz et al. (2020: 63), decolonising involves ‘being comfortable with being uncomfortable’. This idea of being made ‘uncomfortable’ is one we emphasise in our case studies – especially in our example from the initial teacher education programme, where the walking tour of London was entitled ‘The Uncomfortable London Tour’. In the pre-session guidance and reading for the walking tour, we described this as a process of shifting away from the (re)telling of knowledge about particular places and instead foreground the topics that might be easily ignored or glossed over as they require forms of reflection, discussion and new viewpoints to be negotiated.

It is the negotiation of these boundaries between acceptability and controversy that makes efforts to decolonise curricula in schools and universities in the UK all the more complex. In the following section, we outline empirical materials from our two case studies. In so doing, we draw out the different pedagogical techniques through which decolonising takes place.

Methodologies for decolonising a Year 7 geography curriculum

Tracing relationships

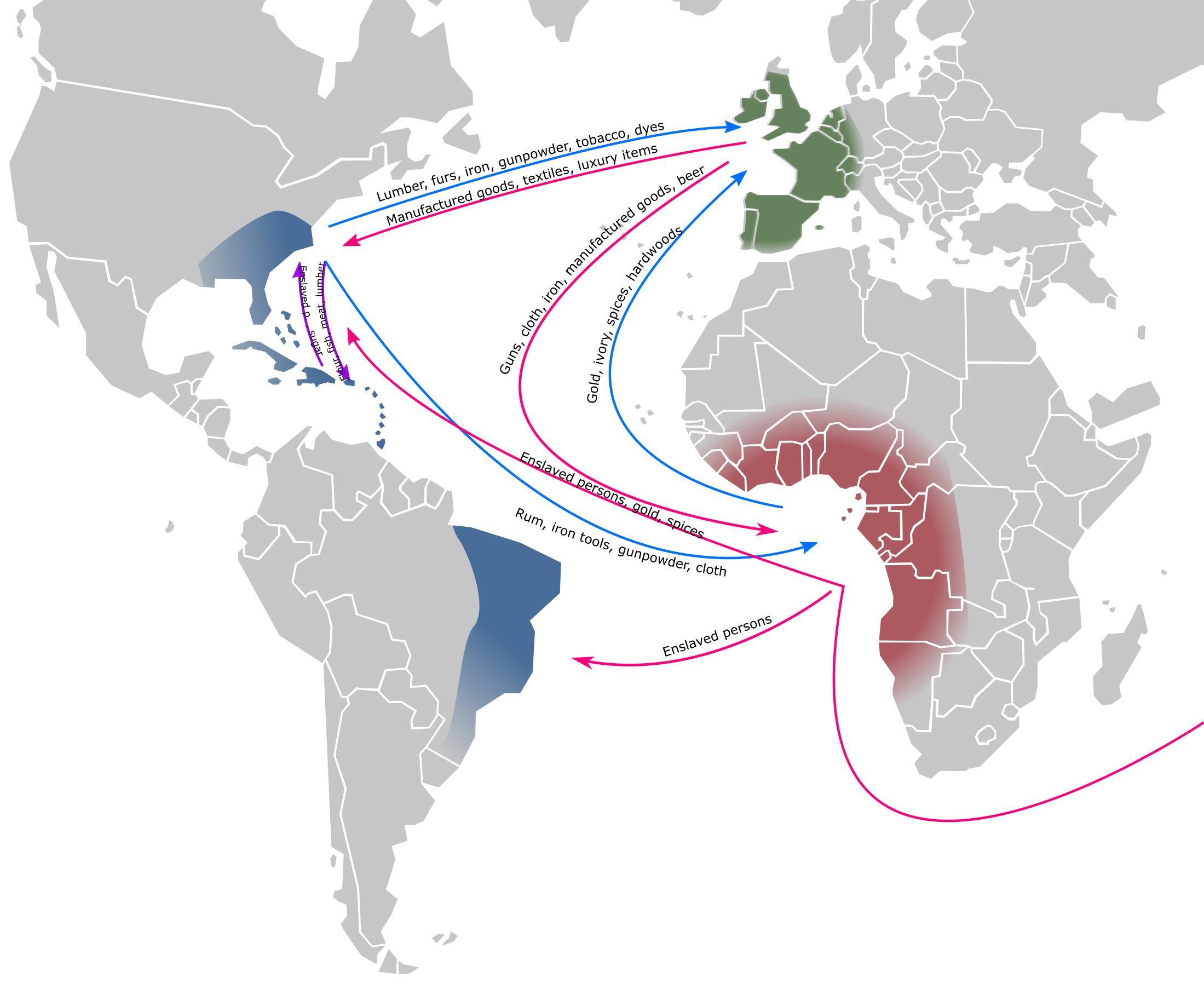

As part of a unit on globalisation, I (CN) wanted students to be able to trace the geographies and histories of colonial influence on London. Figure 2 shows the ‘triangular trade’ in slaves between the UK, Western Africa and North America. Students described this map so that they understood how slave labour was transformed into goods, at the same level as sugar for example, and shipped to the UK, where profit from the sale of these goods accumulated. Figure 2 prompted a discussion about the way that capitalism operates through the accumulation of profit from labour, and several astute students remarked at the way that commodities such as tea continue to draw lines between former British colonies such as India and Kenya in a way that continues to maintain and perpetuate unequal relationships.

Establishing this relational understanding was the first step in allowing students to visualise the connections between modern UK cities and slavery. This allowed scaffolding in subsequent lessons for more complex discussions that required students to apply this approach to thinking about the connections between slavery and contemporary UK companies (Table 3). In one lesson, students were asked to explore the direct and indirect connections between British banks and the slave trade (see Mulhern, 2020), which led to discussions and reflections on how this might influence decisions both about how to open a first bank account and about the banks that students felt they wanted to use. In this way, attempts to decolonise the curriculum can link to broader cross-curricular links between geography, history and life skills, for example.

Tracing the historical links between UK cities and the profits and influence of slavery is important for several reasons. First, it helps students recognise the ‘relationality’ of cities in a way that troubles the idea of the city as a point on a map that is confined in space and time. Geographers have noted how cities are established and maintained through linkages and flows of materials and people that expand what we geographically understand by cities (for example, Massey, 2005). Second, experiences of cities can be ‘haunted’ by their past, such as the lingering ways that colonial architecture can affect how people experience cities (for example, Till, 2005).

These conversations around the way slavery has benefited UK businesses and shaped cities became more personal and applied as lessons progressed through the scheme of work (Table 3). While students were initially introduced to the concept of slavery and the idea of ‘triangular trade’, in later lessons, the emphasis shifted towards how the legacy of slavery feels as it materialises in the architecture of cities, and what students felt should be done about it. These questions play to the strength of geography as a subject which has the potential to expose learners to genuine social and environmental issues. In these lessons, students were asked to think about how they felt walking past statues of slave owners and to reflect on how this might be different for different groups of people. This was an exercise in developing student empathy in trying to think about what might initially seem an innocuous and unnoticed part of a city, through different perspectives.

The scheme of work culminated in a task that asked students to research the ways that London architecture and street names have a colonial legacy and to design their own vision for a London that was ‘welcoming to everyone’. This task was designed to allow students to apply what they had learnt through the lessons in a manner that allowed knowledge to be assessed; it also encouraged students to envisage more equitable futures. This is a form of speculative storytelling that is about thinking creatively and expansively about what futures can and should feel like.

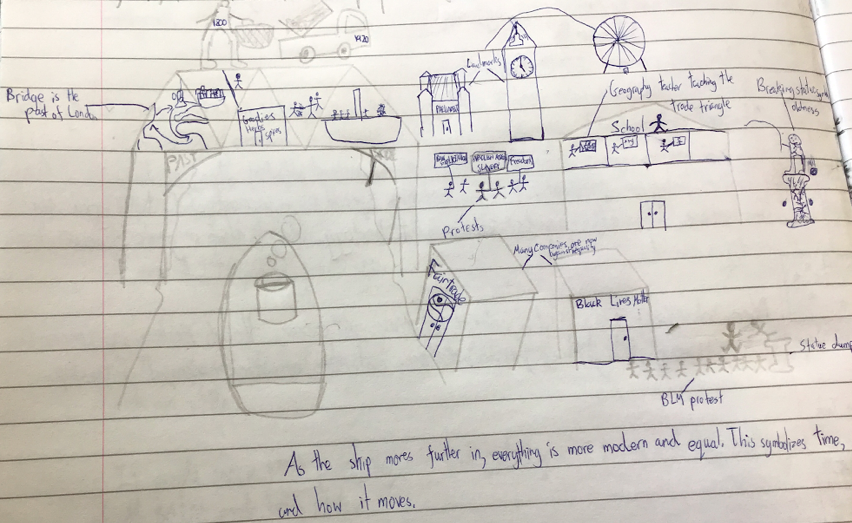

Figure 3 shows an illustration of a student’s response to the task of creating a more equal city. It is clear that they have thought carefully and creatively about this task. The writing at the bottom of the page reads: ‘as the ship moves further [sic] in, everything is more modern and equal. This symbolises time and how it moves.’ There is a sense here of leaving some elements of the past to decay, such as a statue of a slave trader. The image shows how the student is thinking about ethical businesses and fair trade alongside aspects such as the school curriculum and the Black Lives Matter protests.

In addition to the sentence at the bottom of Figure 3, the student also includes various elements that for them characterise a more equal world. These include a group of people being able to protest about ‘freedom’ and an end to ‘modern slavery’. The students were taught about modern slavery as part of a class discussion on the way that slavery continues in the twenty-first century, and this student recognises that struggles to eradicate slavery are important and ongoing. Figure 3 also shows a teacher in a school teaching ‘the trade triangle’ – a reference to the content about which they had been learning. This shows a certain level of recognition that content in schools also plays an important role in anti-racism. Another element to Figure 3 is a feeling that statues of slave traders should be taken down. Discussion of statues did not feature as part of the lesson sequence; this feature shows the student bringing in ideas from outside the classroom, and connecting these broader debates to the task.

What is revealing about this scheme of work, however, is not only the representations the students drew, but also the ongoing conversations around race, identity and equality that propagated through subsequent schemes of work. For example, as intimated in the introduction, two students used the ideas from the lessons to start a podcast themed around issues of race. These students also felt confident sharing a Panorama BBC television documentary entitled ‘Am I British?’, which looks at the systematic discrimination that young people born in the UK experience. Figure 4 shows this post from the student on the class digital classroom, accompanied by the student’s own description of the documentary.

This example thus highlights the complexity not only of how we decolonise the curriculum, but also of how we assess the success of this work. Tasks such as that shown in Figure 3 may give educators an opportunity to assess the way that concepts are being applied, and how knowledge from previous lessons is being brought into a task, but these tasks also require a great deal of thought from students, illustrating their effort in grappling with these complex themes. It is Figure 4, however, that may be more indicative of the effectiveness of this attempt at decolonising. The scheme of work allowed ideas of racism to be validated, such that a student could feel confident sharing a documentary that spoke to themes that resonated with them and their lived experiences. It is this relatively small – but likely significant for the student – practical act that speaks to the student’s increased confidence and agency.

Methodologies for decolonising the curriculum in a PGCE geography course

The materiality of place: ‘uncomfortable’ walking tour

Truman and Springgay (2019: 527) suggested that walking tours are ‘a research method, a tourist event, and an everyday practice that are a ubiquitous method of getting to know a place, including its hidden histories, obscure stories, and state-sanctioned narratives’. They contended that:

conventional walking tours can reinforce dominant histories, memories, power relations, and normative or fixed understandings of place. This place-based knowledge can serve various forms of governance or ideology and maintain the status quo, including the ongoing violence of settler colonisation and erasure of racialized, gendered and disabled bodies.

Our walking tour of London was intended as an opportunity for teachers studying at a central London university to rethink familiar places, and as a chance to attempt to do what Daigle and Sundberg (2017: 1) described as ‘unsettle Eurocentric colonial discourses that many students carry into the classroom’. The tour created openings for trainee teachers to raise points for class discussion, and to think through how they might adapt ideas from the walking tour to incorporate into their own teaching in secondary schools. We note that due to COVID-19 restrictions we were not able to carry out the walking tour in person as a group and that this important aspect of physically walking the path towards greater decoloniality together was not possible on this occasion.

Creating the walking tour required us, as the ‘educator-guides’, to begin by troubling our own taken-for-granted ideas about these places which we encounter and interact with on a semi-regular basis. Our hope was to introduce the trainee teachers to the silences and debates which each site prompts, but importantly to ‘unsettle’ and ‘surprise’ our students with the way colonial histories of familiar places have been silenced. It is through mobilising these emotions and affects that we wanted to inculcate a sense of why decolonising matters.

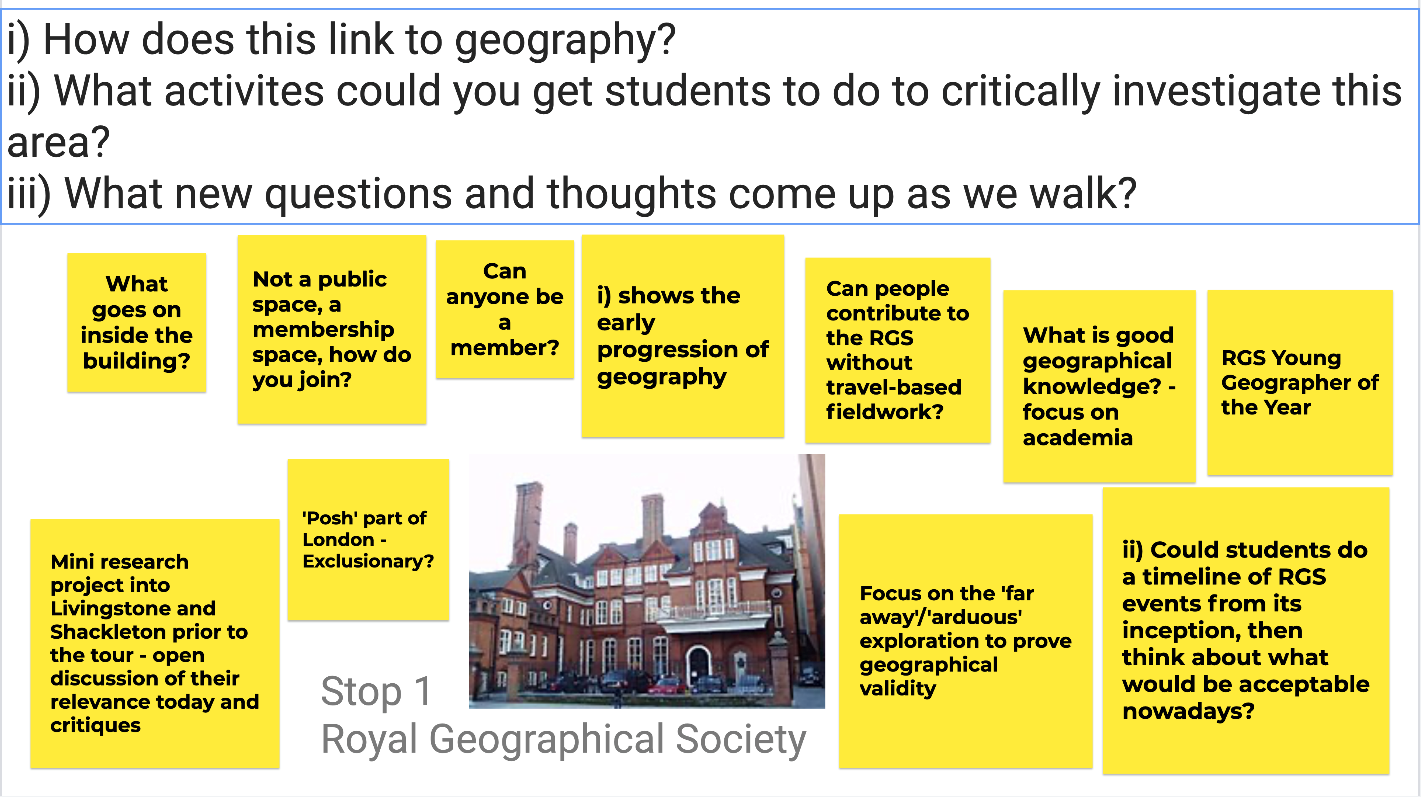

The tour started at the Royal Geographical Society. The RGS plays an important role in UK geography education. For example, it provides classroom resources, hosts internationally regarded conferences and organises competitions for secondary school students. Yet, the history of the society was ‘closely allied for many of its early years with colonial exploration in Africa, the Indian subcontinent, the polar regions, and central Asia’ (RGS, n.d.b: n.p.). We therefore wanted teachers to be aware of this history, and to reflect on some of the ways in which colonial visions of the world still inform the discipline of geography, its subject matter and its pedagogies. The answers to these questions were not prescribed, but the questions were framed as provocations for the trainee teachers to reflect on using a Jamboard (Figure 5).

Figure 5 shows the ways that the trainee teachers are beginning to think through practical classroom tasks that ask students to question the importance of elements of the geographical canon. For example, one trainee teacher suggests the need for ‘open discussion of the relevance’ of explorers such as Livingstone and Shackleton. Another trainee teacher suggests a practical classroom activity involving creating a timeline of the history of the RGS to get students to reflect on ‘what would be acceptable nowadays’ (Figure 5).

Between the stops on the tour led by CN, students were invited to share their ideas and enter into a conversation facilitated by ER about the relevance of each place. These conversations generated important considerations of the ways that race, class and gender intertwine in particular places to create social exclusions. They matured as the tour progressed, with a greater focus on the places in between the official tour stops emerging as teachers discussed themes such as gated private gardens and the role of Black domestic labour in the UK economy.

At the tour’s second stop, the Victoria and Albert Museum and Natural History Museum, trainee teachers reflected on questions related to the way that many objects in European museums are stolen and curated as the spoils of empire (Hicks, 2020). The Jamboard reflections from this stop incorporated questions which could give rise to perceptive enquiries and tasks for classroom lessons, such as:

- (1)

‘Does the museum have to have the exact object? Today’s 3D printing technology could easily replicate an artefact? Handing it back only adds to the history as well?’

- (2)

‘What are the debates re: returning objects in the countries from which they were taken? Presumably they want them back but is this a government priority?’

- (3)

‘Visit various objects within the museum and strike up a debate as to whether they should be returned and why?’

At the tour’s third stop, Sloane Square, the focus of the tour shifted to the embodied experiences of space. Emphasis was placed on how individuals feel in a particular space, and the association of places with those who were directly and indirectly involved in the slave trade. Here, key themes represented on the Jamboard centred on how students in the classroom could investigate perceptions of space. For example:

- (1)

‘Students could design a survey, ask pedestrians how they feel about the place, then explain some history, then ask if their perception has changed?’

- (2)

‘Maybe a class GIS map of London with photos of the area and some research? Could make a great wall display.’

- (3)

‘Are there other people associated with this area who we could be celebrating?’

At the fourth stop, Buckingham Place, ideas of the Commonwealth were explicitly explored. Students discussed the tensions around the celebration of the Commonwealth, and different opinions of the monarchy. There were many perceptive ideas for classroom discussion here that could equally form the basis of new enquiry-based units, such as:

- (1)

‘Are events like the Commonwealth Games a reminder of a colonial past or a celebration of joint history?’

- (2)

‘Ex-colonies: then and now’

- (3)

‘Students can ask visitors why they are here (and where they come from), what associations visitors make/what made them come see the palace?’

Parliament Square was the fifth and final stop. The idea here was to reflect on the way recent government decisions had discriminated against Black communities such as the Windrush migrants, and how this should be taught in schools. This was an area that trainee teachers found much harder to reflect on, likely as a result of worries around politicisation of the discipline (Standish, 2012), and perhaps concerns about being too ‘overtly political’ in the curriculum. The construction of the walking tour in a way that progressively made issues of race and colonialism less abstract and more immediate was a deliberate pedagogical device used to scaffold the tour. It served to allow trainee teachers the chance to grapple with what we as teacher educators regard as increasingly challenging areas because they involve reflecting on, and opening up debate around, complex and contested contemporary issues.

Conclusions and reflections

We began by outlining three approaches that characterise what we consider to be dominant ways of approaching decolonising the geography curriculum in secondary schools in England. We then described how we both approached the task of decolonising the curriculum in our own work as teachers and educators in a secondary school and university setting. We highlighted how our approach is one that focuses on enabling agency in our students. For trainee teachers, our goal was for them to develop the ability to apply ideas of decolonising the curriculum in their own practice. For secondary school students, the aim was to encourage them to feel confident in discussing issues of race and racial discrimination in the classroom, and to take positive, productive steps to learn more about these issues.

We have shared two practical approaches to decolonising the curriculum in a school and a university setting. This contributes to the growing body of work on decolonising the (geography) curriculum by showing the different ways in which it can be achieved in practice. The two case studies show quite contrasting approaches. The example from the Year 7 classroom focuses on developing relational understandings and interconnections. In contrast, the walking tour of London was structured to allow a material and sensuous engagement with key sites in London.

The outcomes from both methods are interesting to compare. The walking tour generated a rich set of reflections and discussions that show that a wonderful set of possible new lesson enquiry questions were generated as the tour progressed. These thoughts require further elaboration and unpacking, but they have the potential to provide a wealth of new avenues for teaching geography in secondary schools. These could be incorporated into existing schemes of work, or potentially used to construct new units. The Year 7 lessons meant that the students learnt the key concepts of globalisation, but in a way that also enabled them to reflect on issues of slavery and its continued influence on students’ lives. What was most positive was how discussions of race and racism normalised these conversations and led to the theme being continued to be discussed through latter topics.

There is, however, a vacuum of government guidance and support on issues of decolonising the curriculum. For example, the term ‘decolonising the curriculum’ was mentioned briefly only once in the ‘Sewell report’ on Race and Ethnic Disparities (Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, 2021). Educators therefore are left having to weigh up if the teaching of ‘uncomfortable’ histories and ‘uncomfortable’ presents that disrupt certain ideas of British nationalism and pride are legitimate, appropriate and possible.

Daigle and Sundberg (2017: 338) described how their approach to decolonising a university degree programme ‘blurs the boundaries between our teaching responsibilities and our personal political commitments to movements for decolonisation and Indigenous self-determination’. We would, however, argue that in curriculum-making the teacher is an ‘active professional who does not just deliver central content, but instead makes conscious and considered choices’ that shape teaching and learning practices (Dessen Jankell et al., 2021: 66). In this way, the teacher is not a bystander to the knowledge that is delivered; indeed, it is the teacher’s professionalism and academic rigour that shapes what is taught and how it is taught. In the words of one of the reflections from our trainee teachers during the walking tour: ‘Leaving these “stones unturned” [colonial ideas] can be as much of a political statement as opening up discussion in the classroom.’