Introduction

More than ever before, young voters in the USA are relying on social media as a primary source of news and information about social and political issues (Walker and Matsa, 2021). According to a recent survey, youth are turning increasingly to social media to both consume and produce political content, with approximately 70 per cent of young voters (aged 18–24 years) getting political information from social media and 34 per cent producing socio-political content (Booth et al., 2020). At the same time, they are turning away from traditional media for news, despite the practice of editorial review and ethics governing these outlets (Swart and Broersma, 2022). Research has documented both the opportunities and challenges that youth face with online civic engagement, including the role of social media in promoting not only youth activism (Jackson et al., 2020) but also the spread of disinformation during elections (Allcott et al., 2019), and contributing to political polarisation overall (Taylor et al., 2018). As every generation recreates and reinforces democracy, youth today must become critical consumers of online information (Allcott et al., 2019), look beyond echo chambers and internet outrage language (Wollebæk et al., 2019) and rebuild institutions that have systematically disadvantaged our most vulnerable communities.

Previous research suggests that the most effective civic education involves teaching through civic participation rather than just teaching about it (Blevins et al., 2016). Teaching civics through participation online calls for explicit attention to youth digital citizenship. This enterprise, framed as empowering youth to be informed and responsible agents of change in their digital communities, is a central concern of social pedagogy. Following Hämäläinen’s (2015) definition, we take interest in promoting ‘active citizenship – the ability to act socially and display social responsibility while rationally fulfilling personal interests as a member of society’ (p. 1028). Across contexts, social pedagogy is marked by the twin concerns of personal growth and social good, or what Moss and Haydon (2008) describe as ‘increasing participation in the wider society, with the goal that both individual and society flourish’ (p. 397). Like critical approaches to social pedagogy, and building on Freire’s (1972) notion of critical consciousness, we wish to empower youth to analyse the social origins of the issues that affect them and take action (Schugurensky, 2014), while recognising that to do so, they must acquire digital media literacy skills to research, critique and act on information as uniquely positioned members of online networked communities.

The emerging vision of combining digital media literacy with youth civic action has led to recent calls for practice-based, educational solutions (Buchholz et al., 2020; Fernández-de-Castro et al., 2021). In response, we report here on the first year of a design-based curriculum project conducted in Northern California (USA) that helps high school students learn to address social and political issues through civic action on social media. Our aim at this early stage is to present a rationale for the design of our emergent curriculum, offer insights into activities used to support digital media literacy and share the design principles that will guide our next iteration. Although social pedagogy did not frame our work with teachers on the present project, we believe that the project points to valuable interdisciplinary intersections that may help inform future applications of social pedagogy to our work in youth civic action and vice versa.

Method

Design-based research

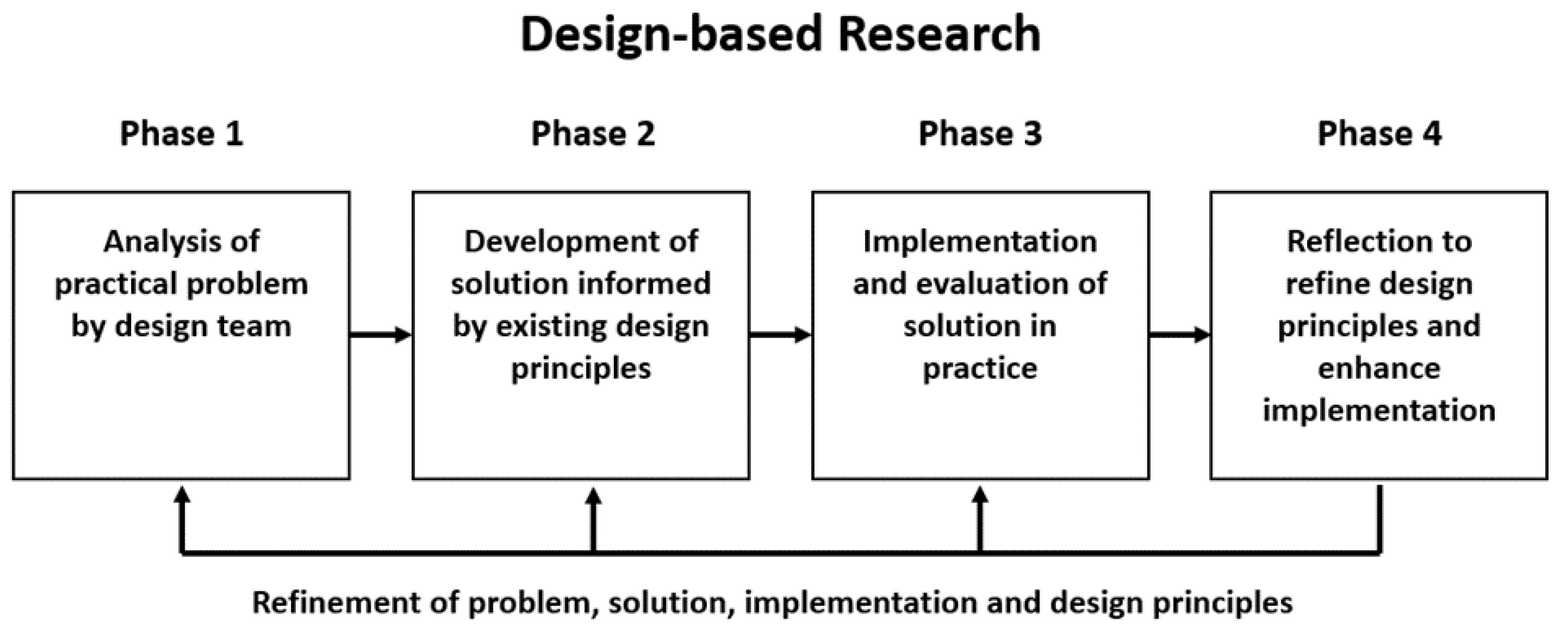

Design-based research is well suited to curriculum development because it emphasises an iterative approach to planning, implementing and refining instruction in complex, practical settings (McKenney and Reeves, 2014). Following Reeves (2006) our process involved four phases: (1) conducting an analysis of the problem based on the extant literature and the practical experiences of the design team; (2) establishing a theoretical framework for developing solutions based on existing design principles; (3) implementing and evaluating solutions in practice; and (4) reflecting on implementation to refine design principles (see Figure 1).

Design team, context and implementation

Given the difficulty of implementing curricular innovations within existing school structures and the limitations of top-down approaches to teacher professional development (Spillane et al., 2002), we built a design team that included both researchers and teachers. The design team began with two researchers and a research assistant with expertise in social media, civic education and deliberative dialogue. Teachers were invited to join the design team using snowball sampling. A project description was circulated inviting teachers to collaborate on ‘developing units of study integrating social issues, digital media literacy and civic action’. Originally, the design team was to include high school students from participating classrooms, but for logistical reasons during the Covid-19 pandemic they were not included in this iteration. Ultimately, five teachers from three schools located in rural, suburban and urban settings in Northern California elected to join the design team. Three of the teachers taught grade 12 government, one taught grade 10 history and one taught grade 9 introduction to education, a class that was offered to students interested in becoming future educators and community leaders. Design team teachers ranged in age from mid-20s to early 40s and had from three to fifteen years’ teaching experience and from one to seven years of experience using action civics projects (including youth participatory action research or student-centred civic action) to teach about government, politics, social justice or participatory democracy (see Table 1).

Teachers, experience (in years) and courses in which the units were implemented.

| Teacher | Teaching experience | Action civics experience | Course |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dan | 15 | 1 | American government |

| Celene | 7 | 7 | Introduction to education |

| Clay | 5 | 5 | AP* government and politics/AP macroeconomics |

| Jessica | 3 | 3 | World history |

| William | 17 | 3 | AP government and politics/AP macroeconomics |

| * AP stands for Advanced Placement. | |||

The design team met as a group four times over the course of the year. The first two design team meetings focused on Phases 1 and 2 of the design process (problem analysis and development of solution informed by existing principles); additional one-on-one direct-support meetings focused on planning for Phase 3 of the design process (implementation and evaluation); and the third and fourth meetings focused on Phase 4, using student work analysis to guide the process of reflecting on and refining the design principles. Teacher insights on the impact of the curriculum on student outcomes was corroborated through a combination of student work analysis and teacher interviews. In the third and fourth meetings, a four-phase tuning protocol (McDonald et al., 2015) was used to analyse student work. The protocol began with teachers presenting the context for the student work. Next, the design team asked clarifying questions about the context, and then reviewed the student work samples, offering interpretations of student learning. Finally, the presenting teacher responded to the team’s interpretations and commented on lessons learned. Teacher interview data cited throughout this article was taken from a subsequent set of reflective interviews with teachers conducted at the end of the project. These data were analysed by the first author using thematic analysis and iterative analysis of notes, which were then reviewed and discussed with the second author as an additional corroborative check.

Findings and discussion

Phase 1: problem analysis

At the first design team meeting, the group explored the problem space, reviewing recent research and exchanging experiences teaching civic education. In the conversations that ensued, which focused on teachers’ curriculum, their students and the role that social media plays as a source of information about social and political issues, two themes emerged to define the problem space: the need for digital media literacy and the need to address youth as consumers, conveyors and producers of information online.

Digital media literacy and apt epistemic performance

The rapid unchecked proliferation of information from online news sources presents unique opportunities and challenges for civic education. Unprecedented access to sources ranging from personal accounts to scientific publications has not only made the public more informed, but also more sceptical about information and the nature of knowing. Kavanagh and Rich (2018) argue that four trends are contributing to what they call truth decay: (1) heightened bias in information and disagreement about facts; (2) blurred lines between opinion and fact; (3) increased influence of opinion across multiple media; and (4) diminished trust in traditional media outlets. Ironically, mistrust in the objectivity of legacy news sources has contributed to a preference among youth, who consume much of their news on social media, for more opinionated sources that openly criticise traditional news outlets while eschewing journalistic standards for reporting (Marchi, 2012).

These conditions call for a curriculum to specifically address social epistemology in online settings, or the ways in which knowledge claims emerge, take shape and take root in digitally networked communities. Our design team adopted the AIR model of epistemic cognition (Chinn and Rinehart, 2016) to address the need for unique epistemic aims, ideals and reliable processes in using online information for civic action. Students must understand that researching an issue online is an epistemic aim that requires critical assessments of the information that they encounter. They must recognise that these critical assessments call for epistemological ideals about the accuracy of reporting and the effectiveness of political actions. To achieve these ends, they must develop reliable processes for critically analysing sources, fact checking and mobilising their social networks.

Students as consumers, conveyors and producers of information online

Media literacy, particularly in school, generally involves teaching students to apply evaluative criteria to sources (Nisa and Setiyawati, 2019). However, digital media literacy also involves the work of becoming effective conveyors and producers of content when sharing or posting information online, a set of skills less frequently addressed in school (McNelly and Harvey, 2021).

Furthermore, while students may benefit from critically analysing sources in isolated lessons, they may not transfer these skills to real-world contexts where reading, sharing and producing content often occur in a fluid and non-linear fashion (Swart and Broersma, 2022).

Studies suggest that the decisions youth make when critically consuming media do not necessarily map onto decisions about what to share, suggesting that these are discrete processes that youth must learn to coordinate (Middaugh, 2018).

There is a mutually constitutive relationship between receptive and productive skills in media literacy. Studies show that youth feel more informed and empowered about social issues when they create content (Booth et al., 2020). Because of the complex interplay between consuming, sharing and producing content on social media, they must learn to engage these skills in tandem (Lin et al., 2013), particularly when coupled with reflection and dialogue (Celik et al., 2021). Ideally, holistic experiences should help them develop epistemic vigilance (Sperber et al., 2010) about information as they explore and research a topic, as well as epistemic integrity (De Winter and Kosolosky, 2013) when making decisions about whether there is sufficient evidence to support the knowledge claims they use to raise awareness and advocate for action.

Phase 2: theoretical framework guiding solution development

At the second meeting, the research team proposed a framework for curriculum design and development based on the outcomes of the prior meeting. Through a combination of activities, discussions and readings, the design team teachers were introduced to the themes described below by the research team. The design team collectively explored these themes in a workshop, looking at social media posts made by youth activists, focusing on the ways in which these youth framed one particular social issue (climate action) for their followers and issued calls to action.

Supporting civic identity development by engaging students on issues that matter to them

Civic identity development emerges as youth engage with social issues, develop the skills and agency to act, and discover a community with whom they can work to improve public life (Viola, 2020). Research indicates that critical reflection and sociopolitical control fostered through civic education on personally relevant issues (Diemer and Li, 2011) are associated with voting behaviour and civic action outside school. A consensus has emerged in the field of youth civic engagement that high-quality civic education requires some combination of enquiry, dialogue and action in collaboration with others, to foster youths’ critical understanding, sense of belonging and agency as civic actors (Cohen et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2021). This approach has been viewed as particularly relevant for marginalised youth because it focuses on student enquiry into personally relevant issues, structural factors that contribute to the experience of inequity, and students’ commitment to and capacity for contributing to their communities (Ito and Cross, 2022).

Supporting students to develop specific digital media literacy skills

To navigate digital environments successfully as digital citizens, students must learn to use the internet to investigate issues, engage in dialogue to critically evaluate options and mobilise networks on social media to act. Our integrated approach builds on Hobbs’s (2010) essential competencies of digital media literacy, which include the ability to access information, analyse and evaluate messages, create content for an audience, reflect on responsible media use and act to share knowledge and solve problems.

Recent research suggests that there are changes in how the practices of enquiry, dialogue and action are carried out online that have implications for what civic media looks like and how to support it. For example, recent studies find that the majority of youth rely on social media for news and information, letting news come to them rather than actively seeking it out on their own (Clark and Marchi, 2017). A passive approach to news consumption places a greater burden on users to differentiate between entertainment, opinion and evidence-based reporting as they sort through the flow of information that they receive (Hobbs, 2010). First, youth must learn strategies for evaluating online information (McGrew et al., 2018), and also decide when and why to enact those strategies in everyday contexts (Middaugh, 2018). Second, dialogue plays an important role in extending and refining the critical analysis of online information by creating a forum for discussing evidence (Celik et al., 2021). While many action civics curricula include discussion, they do not typically attend to the different purposes of discussion beyond debating the issues. Civic discourse encompasses a broad range of communicative purposes, including political analysis, advocacy, dissent, affinity-group building and deliberation (Lee et al., 2021; Middaugh and Evans, 2018). Studies suggest that deliberative dialogue about social issues and social policy (Felton et al., 2009, 2015) allows youth to hone their ability to critically examine their own and others’ beliefs and assumptions to make civic decisions in collaboration with peers (Hess, 2009). To avoid the false equivalencies of political opinions that can emerge in poorly framed deliberative dialogues, conversation ideally centres on the analysis of evidence and decisions about civic actions that youth can take in light of available options. Finally, with respect to civic action, social media has been simultaneously exulted for its role in facilitating youth activism and maligned for promoting slacktivism in the form of self-aggrandising, ineffective action (Cabrera et al., 2017). As social media has evolved alongside the evolution of recent social movements, we have seen a hybrid approach emerging in which the use of social media for framing issues and for mobilising resources is paired with face-to-face action (Jackson et al., 2020). Thus, teaching for civic action in the digital age requires attention to media production and circulation strategies to raise awareness, advocate an action and mobilise a network.

Phase 3: implementation and reflection

After the first two design-team meetings, teachers applied the theoretical framework described above to the design of curricular units, discussing a variety of learning activities that could be used to support students. Research team members introduced activities and tools that the teachers could choose from and adapt. Teachers then worked independently, with support from the research team, to develop and implement units that fit their respective contexts. Each prepared one unit of instruction that integrated four elements: (1) student research into a socio-political issue online; (2) analysis of posts by youth activists on social media; (3) peer feedback in the process of preparing social media posts designed to inform and issue a call to action; and (4) as a culminating assignment, the design of a social media post (referred to as a knowledge product). Students were not required to post their knowledge products to social media. In what follows, we describe the most common curricular activities used by teachers during Phase 3 of the project and their reflections on these design choices. We have used teachers’ actual first names here, as per their request as project collaborators.

Student choice and engagement

All five teachers spoke of the value of student choice for increasing personal relevance and engagement in their projects. Celene, who works with students from a social justice academy, started the unit with an open conversation about the change that they would like to see in the world. She discovered that many students were already using social media to explore personally relevant issues:

I gave them a lot of [youth activist] accounts that I wanted them to look at, but then they also got to choose their own and the ones that they chose on their own showed me that the main focus for a lot of students was mental health, so that was awesome to see that a lot of them were already following mental health-based accounts.

Dan noted that while he had previously taught a unit where students researched a contemporary issue and proposed legislation to address it, the outcomes of that work seemed less authentic and less relevant than the social media project:

When the project about social media was proposed, to me it felt more relevant to their lives [and] I could use the structure of the previous assignment and kind of tweak it to now you’re going to leave here with an actual takeaway.

Several of the teachers also pointed out that the project tapped into a unique set of student assets. Dan found that a student who had struggled to complete a single assignment earlier in the year successfully completed this one. Jessica found that students who did not complete writing projects were more inclined to engage:

There were some students who ... would not participate as much when it came to essays or class discussions. But when I assigned the TikTok video, eyes were open, they were listening ... those were some of the students [who] finished the project first.

Ultimately, giving students the freedom to choose their topics produced a wide range of projects that reflected their diverse interests and concerns. They advocated for local legislation in support of climate justice, rental and mortgage assistance programmes to mitigate homelessness, networking with activists for Indigenous women’s safety and pressuring elected officials to protect reproductive rights in upcoming legislation. To help students move from choosing a topic to advocating for action, teachers then scaffolded students’ skills of enquiry, dialogue and action.

Scaffolding enquiry

Teachers had students develop social media posts as knowledge products that aimed to both inform the public and issue a call to action. While some students in each classroom had prior experience with civic action on social media, many did not. For this reason, teachers opened their units by having students explore youth activist accounts. Analysing models of knowledge products early in the unit helped students grasp how research can lead to civic action and inspired them to engage. As William explained:

This gave them a chance to see what was being done and what was out there in terms of social media and really trying to influence people. And so, it gave them a different view about how to transform [the research] they were doing in a way that everyone would get.

Teachers used models not only to inspire students and shape their understanding of the task, but also to encourage students who might not otherwise see themselves as change agents. As William put it:

This made it more real, because they got to apply it to something that they already knew and were more familiar with, and the idea of reaching out to representatives is something that is very new to them and feels a little bit uncomfortable, but when they saw it more available, and they saw more people that were engaging in this kind of activity, I think it just made it seem like it was more natural.

Many teachers also used sample posts to help students to reflect on the effectiveness of youth activists’ methods. For example, for Clay’s students:

[They] discussed social media artefacts that they found on sites to determine what [distinguishes] a good social media post from a bad social media post and how social media can be used effectively to create change.

Several analysed the use of hashtags to increase the visibility and reach of youth activists’ posts. Engaging students in this way positioned them as both consumers and producers of online activism in ways that were mutually reinforcing.

To scaffold student enquiry in their units, teachers implemented a combination of traditional strategies for supporting research using legacy media and new strategies specific to social media. Dan chose to balance issue exploration on social media with research in academic databases, encouraging students to check claims made on social media against vetted sources. He then had students cite their sources in their social media posts, taking care to explain what made their sources reliable. Contrary to common assumptions about youth as digital natives, teachers noticed gaps in students’ knowledge of social media as a tool for enquiry and social action. William pointed out:

They’re posting with their friends or doing things like that, but not a lot of our students necessarily gravitate towards [civic action on social media].

Teachers started by helping students learn to identify relevant hashtags and use search terms when exploring an issue. Jessica and Celene both noted how students needed help with the language associated with their topics. For example, Celene noted that:

[Students] needed support sometimes in naming what it was that they’re interested in ... doing the academic language.

Students’ initial search terms were often too broad, too specific or politically loaded in ways that constrained what they found from online sources. Nonetheless, they found value in online sourcing. Clay noted that switching from traditional sources to social media opened up new avenues in their research:

I think it was going out onto social media and searching for their policies or their topics on social media that allowed them to have a deeper understanding of their topic ... using social media allow[ed] them to see local stakeholders ... involved [with the] policy that they’re trying to change.

Exploring issues in this way exposed students to a range of perspectives to critically examine. For example, William, Clay and Dan all spoke about having students consider not only who the source is, but also what motivated the choice of information to post. This additional exposure, which leveraged students’ talent for online navigation, complemented more traditional research into their topics by giving students fresh perspectives on how to move from collecting information about potential policies to critically analysing stakeholders’ social and political perspectives.

Scaffolding dialogue and feedback

Once students had researched their issues and surveyed the online political landscape, they were ready to craft social media messages to inform their social networks and advocate for action. At this point in their units, teachers used dialogue as an opportunity for students to share their preliminary ideas and get peer feedback. Doing so positioned students as peer-mentors, leveraging their learning thus far to critique each other’s evolving plans. In fact, Clay felt that peers might be better sources for feedback and ideas than the teacher:

Sometimes that’s more helpful, hearing from a peer versus the teacher. The only wish that I had is [that] I started early on in the semester, because I felt like it would be helpful for the students earlier on in the project to kind of use dialogue to better navigate the project.

Dan found that students were able to support each other despite differences in their topics:

They’re actually surprisingly good at leading the groups and taking their prior knowledge and guiding other groups to ... ‘here’s what you might want to do with your project’.

However, preparing students to engage in dialogue without teacher direction took preparation. Dan set up Socratic seminars where students filled out planning sheets to structure their social media posts. He found that having students prepare these planning sheets prior to discussion motivated them:

When students feel like they’re an expert in something, they’ll obviously contribute more, or they’ll engage more in the activity.

As a result, they came to the seminar prepared to share their ideas and get feedback from peers on any of the elements of the rubric, which included critically evaluating their choice of audience, message and action.

Preparing for dialogue also meant preparing critical friends for the conversation. Celene found that dialogues were more successful when the whole class was clear about the academic language used in discussion, explaining:

We talked about the importance of defining terms ... what prevents a lot of dialogue in general, people not knowing exactly what is being talked about and being maybe afraid to ask. So just kind of putting that as a norm to define things as you go.

Giving students the opportunity to choose their topics meant that extra effort had to be put into bringing the class up to speed on each topic for the dialogues to work. In some classes, this took the form of presentations prior to dialogue (as in Celene’s, William’s and Clay’s classrooms) or dedicating more time to discussions, so that peers could ask questions and learn more (as in Dan’s classroom).

Finally, Clay pointed to the importance of reflection in developing strategic thinking:

I think the reflection ... whether it was written or the discussion piece of the project [was valuable] because they were able to reflect on what they did well, what they could better improve upon, which I don’t think could occur outside a classroom setting. So, it kind of forces them to reflect on, you know, what is good social media in terms of civic action and what maybe is not good social media in terms of civic actions.

Through peer feedback and deliberation, students sharpened plans for their social media posts and were ready to move on to developing their knowledge products.

Scaffolding social media knowledge products

Over the course of the unit, student participation shifted from critiquing youth activists posts, to collaborating on knowledge products, to working independently. William had students first co-construct a social media campaign for a common issue (one that no one in the class had selected), so that they could discuss potential civic actions collectively before starting on their own topics. As William explained:

It was just good practice for them to ... come up with ideas for what kind of actions they [could] do.

William also found that:

[Students came to realise] that if you want to get things done, and you want to change people’s opinions, that you have to bring attention to issues that you care about. And that hopefully, if you can attract the attention of some decision-makers that you’ve had the possibility of getting things done.

His students used social media as a research tool to find non-profit organisations or politicians who were already engaging with their topics to amplify their impact. Similarly, Clay reports:

I tried to tell students that you can leverage the influence of others on social media to create change, whether that’s reaching out to a politician or somebody with a lot of followers. You could try to use that to your advantage to gain more support for your project.

In this way, students came to see civic action on social media both as a channel for reaching a wider audience and as a way to reach out to key decision makers.

That being said, Clay reflected that he needed to spend more time building students’ confidence to engage with others on political issues:

A lot of them feel comfortable using social media, through a personal lens, whether it’s updating their life, their … you know … their friends, their family, and what’s going on. But I feel like a lot of them weren’t confident in using social media, regarding politics or policy.

Finally, Dan had his students write a creator’s statement, in which students justified their choice of audience, message, information and action, helping students make their thinking explicit and hone their knowledge products. This also helped Dan evaluate his students’ work, giving him access to both the product itself and the thinking behind its design. The design team is now exploring the idea of having students also write a dissemination plan, to have students consider how to build a network and increase the reach of their posts.

Phase 4: refining design principles

From the outset of the design process, our team sought to empower youth as consumers, conveyors and producers of civic action on social media. Given the unique nature of knowledge claims, exchange and production online, we focused on fostering apt epistemic performance in the digital realm. In the next sections, we discuss five curricular design principles proposed by Chinn et al. (2021), adapting them to our work and addressing how they contribute to the growing literature on youth civic engagement on social media.

Designing increasingly authentic learning environments

Chinn et al. (2021) point out that all too often students are given carefully curated sources to critically evaluate. They argue that decontextualising source work in this way can undermine the transfer of target skills to real-world contexts. Given that so many students get their news online, focusing civic action on social media naturally facilitates the near transfer of media literacy skills to students’ daily lives. As Clay put it:

They’re on social media already. So, it’s using relevance to make students more critically engaged in the world around them.

Perhaps even more importantly, allowing students to choose personally relevant issues heightened their critical engagement. As Celene put it:

They took the civic action project more seriously ... I saw a lot of really deep work from some students [who] maybe hadn’t been putting in as much effort, or you know were kind of just doing a cursory job before.

Focusing on relevant content made media literacy meaningful to students, helping them grasp when, why and how to apply strategies in a holistic way.

Despite these advantages, some teachers expressed concerns about the risks of having students post on social media. The teachers were fine with having students online for the enquiry portion of their projects, but asked students to discuss and design knowledge products without actually posting them. Their solution not only increased safety, but also limited students’ access to insights about using social media for outreach, building networks and circulating information. The challenge of balancing authenticity and youth voice with protection is a common tension within youth civic education. We have seen that when youth share their concerns on the internet and social media, they have the opportunity to see that what seem to be personal problems are actually problems of public policy (Middaugh and Evans, 2018; Middaugh and Kirshner, 2015). At the same time, youth themselves are aware of the risks associated with online civic expression such as the potential for reputational damage, exposure to conflict or having their ideas misrepresented or taken out of context (Weinstein and James, 2022). Some adaptations we have seen involve creating protected and moderated sites where youth can engage with a mini-public of peers working on similar projects at other schools (Middaugh and Evans, 2018) or to work on media campaigns as a group with adults providing insight and coaching on the risks while gradually stepping back to allow youth to take the lead at a rate that they feel comfortable with (Kirshner, 2015). It is particularly important for adults to discuss with youth the potential for negative comments or emotions when posting, as well as strategies for responding to comments (or for disengaging from conflict). We find that having students analyse existing examples of dialogue to be a promising strategy. As our design team work continues, we plan to explore how we can build on lessons learned to create a scaffolded approach to supporting students as they go public with their civic expression while managing the risks of doing so.

Supporting adaptive epistemic performance with bounded knowledge

Public policy on social issues is a complex space where most people have limited knowledge and expertise. Civic engagement sometimes calls for recognising the bounds of our knowledge and drawing on the expertise of others to inform our decision-making. Allowing students to explore issues on social media exposed them to the buzz of competing claims and evidence and forced them to grapple with uncertainty. Dan used this uncertainty to help his students grasp the value of using vetted academic databases to gain insights from disciplinary experts:

I wanted them to not just get stuck in the echo chamber ... That’s kind of one of the things that I want to hit upon in terms of their understanding of how [to] approach these topics when you don’t know all the information ... It’s like, well, if you’re going to, if you agree with something that you read in a social media post ... maybe you need to do some research before you just start echoing the stuff that you’re getting.

Dan’s observation highlights the complexity of evaluating information. To understand ‘truth’ at times it is helpful to surface a wide range of perspectives. Hill’s (2018) analysis of the role of Twitter in providing communities of colour a space to form counter-narratives has been evidenced in recent coverage of the death of Queen Elizabeth II, in which legacy media coverage and social media coverage provided very different perspectives on the historical legacy and impact of the British monarchy. However, there are also times when fact checking among a sea of social media perspectives is not productive and we want to draw on the expertise of a body of research and information by people who have spent years training to understand and distil knowledge. What we have learned from our design process is that it is useful to make those decisions explicit and guide students to be aware of their purpose when exploring knowledge.

Conducting explorations into knowing

Teaching students to seek out expert views from vetted sources is important, but it does not necessarily equip them to become critical consumers of most of the knowledge claims that they will encounter in online spaces. Therefore, students must develop epistemic aims and ideals for identifying biased reporting. Dan had students ask, ‘Who’s creating [this post]? Why are they creating it? How does it affect how they’re saying it?’ Guiding students in this way helps them to recognise that knowledge claims are authored and therefore subject to evaluative standards.

Students can then develop reliable processes for evaluating the quality of evidence online. In the initial stages of units when students are using search terms and hashtags to explore their issues, they have the chance to analyse how different authors use language to frame arguments and compare the different kinds of evidence used to substantiate claims. Teachers should take this opportunity to introduce critical questions such as: What kind of evidence is this? What is the source of this evidence? Is it valid and reliable? How does it compare with evidence used in other posts? Studies suggest that even when people know strategies for evaluating the credibility of information, they often rely on heuristics or implicit strategies when they encounter information in real-world contexts (Metzger and Flanagin, 2015). In the social media format, where news media is consumed alongside entertainment, humour, updates and gossip, it can be easy to forget to use explicit strategies to evaluate information (Swart and Broersma, 2022). Middaugh (2018) found that teens who were taught explicit strategies to evaluate news and information in class would use those strategies in explicit research, but did not engage them when the task switched to decisions about whether to share media online. Thus, part of our approach is to engage students in regular analysis of social media of the type that they may see in their day-to-day lives to encourage awareness of the need to critically evaluate media that comes to them and to develop habits of doing so more frequently.

Promoting virtuous epistemic motivations and emotions

Evaluating bias and the quality of evidence creates opportunities for students to recognise their own responsibilities when sharing items and producing content. As William put it:

Not only are you looking at [a post’s] truthfulness, but also the motive, right, and what it’s trying to get you to do, and when it's trying to act on you. And then by them kind of creating their own source, they had this really, you know, eye-opening experience of being like, ‘Oh, I get it now, you know, like, this is why this is being done. This is why it’s being pitched the way it’s being pitched’.

Teachers can actively elicit students’ metacognitive awareness of epistemic integrity by encouraging them to take responsibility for the quality of the information that they share with their social networks. In our project, teachers had students recognise the importance of carefully selecting and citing their sources. Dan had students complete worksheets on the reliability of each source as a self-check and one of these students even spoke to the reliability of her sources in her social media post.

Reflections on responsible media use have been core to conceptualisating digital media literacy for some time now (Hobbs, 2010). However, the considerations are constantly evolving as the technology and information ecosystem evolve. In the age of circulation or sharing of information as a common democratic practice, scholars have drawn attention to the need to be more explicit about what it means to share information responsibly or with civic intentionality (Mihailidis, 2018). As William notes, this means looking not just at truthfulness but at motive. As we discuss in the next section, it also means thinking about one’s own purpose for sharing and the potential impact on others.

Promoting understanding of epistemic systems

Having students create their own knowledge products provides firsthand experience as epistemic agents. Clay argued that:

By making them use social media as a civic action, they were able to think more critically about how to use social media and also think critically about how they consume social media.

Having students reflect on their experience helps them understand how knowledge is socially constructed, circulated and used for advocacy online, giving them a sense of both the positive and negative potential of social media in shaping public opinion. Combatting truth decay (Kavanagh and Rich, 2018) requires making space for dialogue about how ideas emerge, take shape and take root online and how to balance issue exploration on social media with fact checking and research on social media. To that end, teachers should structure conversations to help students understand how social media operates as an epistemic system so that they can make informed decisions about their information feeds, sharing behaviours and social networks.

When we communicate for civic purposes, what counts as good or valuable information depends on what we are trying to accomplish. Garcia and Mirra (2022) provide a useful framework for thinking about these different purposes in which they discuss composing for understanding, dialogue, persuasion, solidarity, action and counter-argument. Each of these kinds of composition serves the goal of youth civic engagement, but each has different implications for what counts as an effective message. In our work with teachers, we have emphasised helping students to develop a theory of action where they talk explicitly about which audience they want to reach, how to appeal to that audience and how to mobilise them.

Conclusions

This first iteration of our design-based research illustrates how a curriculum that addresses social and political action can provide an engaging and meaningful context for developing digital media literacy skills. Social pedagogy emphasises teaching the whole student without separating out knowledge, feelings and actions (Úcar, 2013). The present project centred student choice on issues of personal interest and concern, to leverage their intellectual, emotional and civic engagement, and thereby established a purpose for integrating the skills of enquiry, dialogue and action. It is important to note that students were not involved in our design team, a provision that we were reluctant to give up because of the importance of including the student voice in participatory approaches to pedagogy, but we plan to include students in future iterations to help inform our work. Nonetheless, the curriculum itself centred students by allowing them to choose their issues and design their own approaches to social action. Fernández-de-Castro et al. (2021) argue that an integrated approach to digital work with youth combines participatory and critical consciousness models of social pedagogy by focusing on democratic participation and its socio-political significance for youth. Rather than emphasising citizenship skills without engaging students’ critical consciousness or mobilising students without fostering participatory decision-making, an integrated approach calls for situating skill building so that students see themselves as active change agents who are motivated to learn both the aims and means of civic action. In our field, we similarly refer to participatory (Kahne et al., 2016) and critical consciousness (Mirra and Garcia, 2017) models as complementary approaches to civic education. In pursuing this work, we have positioned students as both knowers and learners in using social media to foster critical reflection and civic action. We have sought to equip students with the epistemological aims, ideals and processes to effectively and responsibly advance knowledge claims when calling others to action in their digital communities.

Ultimately, we hope that by combining these instructional design elements in this way, we bring the pedagogy of civics education in close alignment with the aims of social pedagogy. Several authors in the tradition point to the ways in which social pedagogy has reflected the social, historical and cultural contexts in which they arose. Hämäläinen (2015) argues that for this reason, the tradition cannot be exported from one country to the next, and he invites one or many traditions to flourish in the English-speaking world. Our work has taken place in the United States at a time of tremendous social and political upheaval. In the midst of increased gun violence in schools, attempts to disrupt the electoral process, widespread reckoning with institutional racism and undeniable evidence of human impact on the Earth’s climate, youth are discovering the need to voice their concerns and take action. We believe that teaching youth to engage in these issues as agents of change in the digital world offers fertile ground for applying social pedagogy to the work of promoting individual and collective growth.