Introduction

The United Nations’ Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (2004–14) endeavoured to provide schools with resources to educate their students towards a more sustainable future (United Nations, 2015a, 2019; UNESCO, 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). Many countries around the world now include global citizenship education (GCE) in their school curricula; however, according to Goren and Yemini (2017) and Davies et al. (2018), approaches and quality of instruction vary.

Global citizenship in schools is not just focused on education and Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4. The global goals encourage citizens to work together to maintain peace and justice. Living sustainably and being aware of inequalities allow children to think about the world in which they live as global citizens. It could be argued that the 17 SDGs are a checklist that global citizens should be aware of, investigate and campaign for. Educating the current generation in these areas, linking their learning to the SDGs and discussing their importance could have an influence on whether the goals will be achieved by 2030 (United Nations, 2015a, 2015b, 2019).

Global citizenship

Global citizenship is a concept for which educators, charities and regulatory bodies have been advocating for some time. There are many perspectives on what global citizenship entails. Davies et al. (2018) combine the ideologies of globalism, nationalism, internationalism and cosmopolitanism in their exploration of global citizenship. They focus on the key concepts of justice, equality, diversity, identity, belonging and sustainable development. To investigate perceptions of global citizenship, Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) created a model that tests the antecedents and outcomes of respondents and compares them to their self-identification as global citizens. Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013: 860) define global citizenship as an ‘awareness, caring and embracing cultural diversity while promoting social justice and sustainability, coupled with a responsibility to act’. Their definition appears to be a reflection of what a global citizen might look like, portrayed in different contexts around the world, and matches the majority of themes contained within the literature (Price, 2003; Gaudelli, 2009; Oxley and Morris, 2013; Reysen and Hackett, 2017; Davids, 2018; Isaacs, 2018; Kiwan, 2018; Shultz, 2018; Soong, 2018).

Considering the power relations between the Global North and Global South is important. What needs to be acknowledged are the differences in cultures and beliefs that allow citizens to be global (Andreotti, 2006). Soong (2018: 165) points out that ‘to be a global citizen can mean different things to different people’, especially if there is a lack of clarity or a difference in the aims or presentation of GCE. For the purposes of this research, the nine constructs of global citizenship are defined using Reysen et al. (2013: 860) where global citizenship is an ‘awareness, caring and embracing cultural diversity while promoting social justice and sustainability, coupled with a sense of responsibility to act’. The constructs are:

global awareness: knowledge of the world and of people’s interconnectedness (Dower, 2002a; Oxfam, 2015a, 2015b)

normative environment: the cultural patterns and values of cultural citizenship through people and settings (Pike, 2008)

intergroup empathy: concern for and connection with others outside one’s own group (Golmohamad, 2008; Oxfam, 2015a, 2015b)

valuing diversity: valuing diverse cultures around the world (Dower, 2002b; Golmohamad, 2008)

social justice: the equitable and fair treatment for all and the upholding of human rights (Heater, 2000; Dower, 2002a, 2002b)

environmental sustainability: the protection of the environment and a belief in the interconnectedness of humans and nature (Heater, 2000)

intergroup helping: helping others outside of one’s own group through donations and volunteering (Dower, 2002a)

responsibility to act: acting morally for the betterment of the world (Dower, 2002a, 2002b).

Students’ perception, understanding and display of global citizenship

The traits of a global citizen have been tested and investigated to determine whether students identify with these characteristics. Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) and Reysen and Hackett (2017) state that global citizenship identification predicts the degree of endorsement around prosocial values and behaviours. Therefore, it is possible to predict the antecedents and outcomes of global citizenship through a self-identification protocol.

In a study of undergraduates, each of the following was rated: global awareness, normative environment (people and setting, such as friends and family), intergroup empathy, valuing diversity, social justice, environmental sustainability, intergroup helping, responsibility to act and self-identification as a global citizen. A student’s normative environment was found to be a strong predictor of global citizenship identification. In other words, if a student perceives that their friends, family and those close to them see global citizenship as positive, then they are more likely to self-identify as a global citizen (Reysen and Katzarska-Miller, 2013). In both of their studies, Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) found that all the assessed variables were strongly to moderately correlated with one another. Global citizenship identification was predicted by normative environment, which in turn predicted a greater support of prosocial values. Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) also suggest that valuing diversity and multiculturalism is fundamental in the self-identification of global citizens. Although there is comparatively little research on how students feel about global citizenship or the traits that comprise a global citizen, in the following section we set out research that has been carried out around the antecedents and outcomes of global citizenship.

Antecedents and outcomes of global citizenship

Intergroup empathy

Hull and Stornaiuolo (2014) carried out a three-year study to consider the display traits of students (described as cosmopolitan citizens) from the United States and India. The project examined how young people from two worlds that are seemingly disparate achieve mutual understanding. Both sets of students assumed that they had empathized with the other and had an understanding of the stories that were shared through films. However, Hull and Stornaiuolo (2014) concluded that the empathy displayed on both sides was superficial. Students thought that they were able to put themselves in the others’ shoes. Although they found similarities between their situations, they stayed rooted in themselves, making it hard to see beyond their own experiences. As a consequence, both sets of students felt unheard, even after sharing their stories. Both groups believed that they had not been understood and that there was a lack of empathy towards what was being conveyed. This finding accords with Mackenzie and Leach Scully (2007) who say that it is not possible to put yourself in someone else’s shoes if they are from a very different environment. We cannot try to imagine being someone else from the inside. It may be possible to imagine being in different situations and recognize that others exist in those conditions. But this is limited to imagination as engagement with the perceptions and experiences of others is not possible.

Edge and Khamsi (2012) report the impacts and benefits for students involved in an international school partnership programme. The programme connects UK schools with schools in 13 sub-Saharan African countries. The countries involved in the programme are Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Nigeria, South Africa, Tanzania, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe (British Council, 2011). Edge and Khamsi (2012) surveyed a random sample of 900 of the students involved in the programme. Their findings suggest that the international school partnership programme helps students from different countries around the world to develop cultural awareness and empathy.

Responsibility to act and social justice

Niens and Reilly (2012) examined GCE in a post-conflict context with students in Northern Ireland. They found that students had a strong inclination to act appropriately in matters of social justice. They also had an awareness of interdependence. However, there was ‘little evidence that participants, whether primary or post-primary, appreciated global interdependence in relation to themes other than the environment and … the economy’ (Niens and Reilly, 2012: 108).

Another piece of research from Africa by Quaynor (2015) decribes a case study of 33 school students (between the ages of 15 and 31) living in post-conflict Monrovia, Liberia. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with these students who believed they were global citizens living in poverty, without freedom of speech, and because of this, felt discriminated against. The issue of global poverty and inequality is also one of the major concerns expressed by young people in the Global North when studying global citizenship (Hicks and Holden, 2007; Minty, 2010; Holden and Minty, 2011).

Valuing diversity

Evidence was found in Northern Ireland that students had awareness of other cultures. They also showed empathy and curiosity. There was also some stereotyping about the Global South, which mostly went unchallenged (Niens and Reilly, 2012).

Ross and Davies (2018: 29) stated that young people in Europe have been interested in extending learning about human rights to ‘include areas such as the rights of those with lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender sexual identities, and … the rights of migrants and refugees’. Young people largely accepted refugees from other countries and cultures and were critical of the prejudiced attitudes they attributed to older people.

Sustainability

The environment, climate change and sustainability are all high priorities for many students around the world. This is demonstrated in student-led protests around the world against climate change, initially led by Swedish student Greta Thunberg (Nevett, 2019). There is also evidence that concerns around the environment feature highly in research undertaken with students in the UK and Poland (Minty, 2010, cited in Ross and Davies, 2018), and in Latin America where students are taught that their responsibility as a citizen is to change attitudes to the environment (Sant and González Valencia, 2018).

Normative environment

Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) say that a student’s normative environment is a predictor of whether or not they will self-identify as a global citizen. Shultz (2018: 253) questions this, asking whether GCE ‘produces in some cases, a neoliberal citizen attempting to live without connection to place or people or system’ if it works to expand privilege for elite citizens. However, Shultz (2018) does use the analogy of a classroom being a fractal of the world and if teachers are encouraging an environment in which the traits of global citizens are seen positively, then students will learn to operate in a collaborative, diverse and accepting society. If this is true, then the normative environment would be a definitive factor in whether students feel that they are global citizens. Lee et al. (2017) also found that a student’s normative environment was significantly, positively correlated with self-identification as a global citizen. Howard et al. (2018: 507), in a study of wealthy Ghanaian students, suggest that ‘staying in Africa leads to a limited future’ and global citizenship exists ‘outside Ghana’. The students and teachers refer to Africa’s brain drain. The school in this study offers courses in several European languages and classes are taught in English, reinforcing the message of being ‘depersonalized and detached’ from their country (Howard et al., 2018: 508) and supporting arguments around postcolonial understandings of global citizenship education (Abdi et al., 2015; Torres, 2017; Arnot et al., 2018).

Jooste and Heleta (2017) discuss the development of a global competence, rather than global citizenship, as a more appropriate way of assisting graduates from the Global South to overcome injustices and inequalities. There is a need in higher education in the Global South, they argue, for ‘socially responsible, ethical and globally competent graduates’ (Jooste and Heleta, 2017: 40) as this will support countries’ growth and future development.

Present study

There is evidence that the traits of global citizenship and the effects of GCE can be seen in various research contexts around the world, and in some cases (for example, student climate protesters) they are very visible in the Western media. These traits therefore do constitute the behaviours of global citizens, although research has mainly centred on countries in the Global North. There is a distinct lack of research based in Africa concerning global citizenship. The systematic review by Goren and Yemini (2017) cites only two articles based in sub-Saharan Africa (Edge and Khamsi, 2012; Quaynor, 2015), and thus it would appear that global citizenship in this area has not been researched in depth. Quaynor (2015: 20) also notes that ‘large-scale international studies of citizenship education have not included African nations’. This present study in Ghana therefore adds to the growing research interest in the traits of global citizenship.

The primary and junior high school curriculum in Ghana includes a citizenship education syllabus (MOESS, 2007; Hull Adams et al., 2013; Nudzor, 2017) that contains the following topics:

attitudes and responsibilities for nation-building

sustaining ourselves as a nation

how Ghana became a nation

governance in Ghana

how to become a democratic citizen

ethnicity and national development in Ghana.

The students in this study may not have been explicitly taught any of the specific traits that make up a global citizen, yet some of the topics listed above could clearly nurture attitudes related to global citizenship. However, Ghana’s primary and junior high school curriculum for 2019 (‘Our World Our People’) now explicitly mentions global citizenship as a theme (NCCAMOE, 2019).

Method

Participants and procedure

The children participating in this study came from three schools located in poor informal settlements in the Greater Accra Region, Ghana. The schools were known to one of the researchers and therefore convenience sampling was used to select the three schools – that is, they were chosen owing to their convenient accessibility. All children in classes 5 and 6 in each of the three schools who took part in the research were given the opportunity not to participate.

Potential bias concerning this convenience sampling technique is that the sample of schools may not be representative of the entire population. However, we have no reason to believe that the children or schools that took part in this research were different to others in the neighbourhood. Systematic bias could be one criticism of the sampling technique. Therefore, there are limits around generalization and inference about the entire population. This research used a combination of quantitative and qualitative data to help limit the potential for biased interpretations. Using the two approaches provides a more complete understanding of the research questions as well as explaining the research findings more comprehensively. Merging the two forms of data and determining how to interpret the results that diverge are regarded as two of the main advantages of mixed methods research (Creswell, 2002; Driscoll et al., 2007).

Of the 141 children, 54.6 per cent were girls with a mean age of 11 years (standard deviation 1.30 years). Regarding possessions, 89 per cent of the families owned a mobile phone, about half of their homes had a stone floor and 32 per cent had a toilet inside the premises. Most families accessed drinking water via a public well or spring. The great majority of the fathers had an income (95 per cent) and around two-thirds of the mothers were also in work. Regarding the fathers’ employment, the largest category was ‘farmer or fisherman’, followed by ‘trader’ and ‘service worker’. Half of the mothers were ‘cleaners’ or ‘shop workers’. The three most common languages spoken among participants were English (23.4 per cent), Twi (22.7 per cent) and Fante (18.4 per cent). Many other regional languages were spoken, sometimes by only one participant in the sample of 141 children. Of those surveyed, 71.6 per cent answered that they had never visited another country, while 81.6 per cent said that someone in their family (not necessarily an immediate relative) had visited another country.

Children in groups of 20–30 in classes 5 and 6 completed the questionnaire in their own school; for all participants this activity took place in the morning. The principal investigator from the UK was present at all times in each school that participated in order to oversee the data collection. The questionnaire, semi-structured interviews and global citizen activities with each class lasted around 2.5–3 hours. All the children and their parents were informed via their schools of the purpose of the study, that it was voluntary and that the results of the questionnaire would be strictly confidential and used for research purposes only.

Children completing the questionnaires were younger than those participating in the previous research, and many spoke English as an additional language to their mother tongue. To aid the children’s comprehension of the questions, prior to students choosing whether they agreed with a statement, they were shown a series of pictures and given information describing what a global citizen is generally considered to be in relation to the individual questions. This school-based material was taken from Oxfam’s (2015a, 2015b) guide for schools on what makes a global citizen. The guide is ‘practical and reflective’ (Oxfam, 2015b: 4) to help support awareness and learning of global citizenship in the classroom. It provides knowledge, skills and values which learners need ‘in order to thrive as global citizens’ (Oxfam, 2015b: 5) and materials to help teach global citizenship in the areas of globalization and interdependence, social justice and equity, identity and diversity, sustainable development and peace and conflict. Oxfam (2015b: 4) state that the attributes of a global citizen are ‘someone who has a sense of being a world citizen, understands the importance of diversity and amongst other attributes has a commitment to social justice’. The guide offers a starting point to facilitate discussion rather than giving opinions that need to be taught.

Global citizenship survey measures and semi-structured interviews

This section reports the semi-structured interviews carried out with the children and sets out the questions used in each category of the survey. The interviews were undertaken as a qualitative aspect of the research in order to add a Ghanaian context and illustrate local attitudes and understanding around global citzenship.

The survey devised by Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) contains 20 statements related to global citizenship. These items were answered on a five-point Likert scale showing agreement from 0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree, including a middle option of 2 = unsure.

To assess the antecedents and traits of global citizenship, latent measures from Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) were adopted in order to group survey questions into factor scores.

Normative environment: Two items – ‘If I called myself a global citizen most people who are close to me would think that was a good thing’, ‘I think that most people who are close to me think that being a global citizen is a good thing’ – were combined to assess the cultural patterns and values of cultural citizenship through people and settings. When discussing global citizenship with the children, using the Oxfam (2015a, 2015b) resources, they all agreed that it was a good idea and would help the world to be more interconnected, reduce wars and create more equitable societies.

Global awareness: Four items – ‘I know that my actions in my local environment may affect people in other countries’, ‘I try to find out about current issues around the world’, ‘I understand how various cultures of this world interact socially’, ‘I believe that I am connected to people in other countries, and my actions can affect them’ – were combined to form a global awareness index. One of the highest levels of uncertainty revealed by the children was around how their actions were connected to others. The children did not have any knowledge of issues such as climate change, extreme weather conditions, rising sea levels or polar ice caps melting. Even though Africa Climate Week had been taking place in Accra, approximately 35 km from the schools, during the research period, none of the children interviewed was aware that the event was taking place, but all expressed an interest in finding out more.

Global citizenship identification: Two items – ‘I think I am similar to other global citizens’, ‘I would say that I am a global citizen’– were combined to assess global citizenship identification. When asked, the overwhelming majority (96 per cent) of the Ghanaian children thought that they were ‘a global citizen, the same as children from other countries’. They thought that this was important, as by working together with other countries they could help Ghana.

Intergroup empathy: Two items – ‘I am able to empathize with people from other countries’, ‘It is easy for me to put myself in someone else’s shoes regardless of what country they are from’ – were combined to assess concern and connection for others outside of one’s own group. When asked, these two questions prompted discussion among the children as, although they agreed that they were able to empathize, they tried to delve deeper into why it was so difficult to do so. One student commented that it was ‘hard to understand people from other countries because you don’t know how they are feeling’. Thoughts on this topic mainly concerned the children themselves, even though the statements were thinking about other people. When asked to try and imagine how the researcher might feel about their first time in Ghana and in Africa, one student responded that they thought they would feel ‘proud, because you are able to travel’. The response illustrates that generally the children’s ability to empathize was mostly confined to feelings of difference, rather than trying to think of any similar feelings they might have.

Valuing diversity: Two items – ‘I am interested in learning about the many cultures that have existed in this world’, ‘I would like to join groups that help me to get to know people from different countries’ – were combined to assess valuing diversity. The children responded egocentrically in the interviews around questions to do with getting to know people from other cultures, with a common theme of ‘If I know your country and its people, I will be able to visit your country.’ The children saw the benefits of learning about other cultures as being advantageous in terms of them travelling to other countries. When asked, none of the children had thought about understanding different cultures regarding visitors to Ghana or how it could help them to embrace diversity, reduce stereotypes or help to overcome prejudice.

Social justice: Two items – ‘Those countries that are rich should help people in countries who are less rich’, ‘Basic services such as health care, clean water, food, and legal assistance should be available to everyone, regardless of what country they live in’ – were combined to assess the equitable and fair treatment for all and the upholding of human rights. When the children were asked, a common response was ‘if you have the money’ you should ‘help poor people’. In the survey no one disagreed with the ‘basic services’ question, all believing passionately that ‘basic services should be available to everyone in the world’.

Environmental sustainability: Two items – ‘Natural resources should be used primarily to provide for basic needs rather than material wealth’, ‘People have a responsibility to conserve natural resources to make sure we don’t spoil our environment’ – were combined to assess the protection of the environment and a belief around the interconnectedness of humans and nature. Local mining as well as air pollution were quoted by the children as causes of environmental issues, but they could not explain how these would concern other parts of the world.

Intergroup helping: Two items – ‘If I could I would help others who are in need no matter where they are from’, ‘If I could, I would spend my life helping others no matter what country they are from’ – were combined to assess helping others outside of one’s own group. Over 90 per cent of the children agreed or strongly agreed with both statements relating to intergroup helping. The semi-structured interviews also reiterated this result, demonstrating that children were passionate about this area of global citizenship.

Responsibility to act: Two items – ‘It is important to be actively involved in global issues’, ‘It is my duty to understand and respect cultural differences across the globe the best I can’ – were combined to assess felt responsibility to act. When questioned about active involvement in global issues, most children agreed that they would want to attend a local protest, especially concerning an issue such as mining or traffic pollution. However, students agreed that they had not come into contact with any such activity. They did not appear to have an understanding of any actions that they could take as advocates for issues that they were concerned about, nor could any student think of any activities that they could plan independently in this regard.

Structural equation model construction

The analysis was performed with a 95-per cent confidence interval, and structural equation modelling (SEM) was used for the data analysis. This approach enabled the global citizenship conceptual model to be estimated for data fit using proposed goodness-of-fit metrics in the study. SEM path analysis is a useful statistical tool for evaluating the succession of dependent relationships and verifying cause-and-effect relationships between multiple latent constructs (Hair et al., 2010).

Validity and reliability

In order to secure the internal validity of the instruments, triangulation through qualitative analysis was employed through semi-structured interviews. For external validity, the results obtained in this study were found to be similar to those in other studies, supporting a degree of generalizability. Analysis of the latent structure shows consistent reliability of the global citizenship construct compared to other studies (Reysen and Katzarska-Miller, 2013; Lee et al., 2017). All item loadings on each of the factors are also salient and stable, having values greater than 0.5 (Guadagnoli and Velicer, 1988; Brown, 2006). These results also provide evidence that the model of global citizenship is in some ways transferable, cross culturally.

Results

In order to examine the associations between the nine latent variables, bivariate correlations were conducted (see Table 1). Normative environment was significantly correlated (p<0.01) with all other variables, apart from global awareness where it showed significant correlation (p<0.05) and valuing diversity, where there was no significant correlation. Global awareness was strongly correlated with environmental sustainability (r=0.333, p<0.01), intergroup helping (r=0.348, p<0.01) and responsibility to act (r=0.286, p<0.01). Global citizenship identification was strongly correlated with social justice (r=0.269, p<0.01), environmental sustainability (r=0.284, p<0.01) and intergroup helping (r=0.320, p<0.01). There were strong correlations throughout the variables, with the exception of the construct of intergroup empathy, where the only significant correlations were with normative environment (r=0.236, p<0.01) and responsibility to act (r=0.250, p<0.01). Responsibility to act was significantly correlated with most variables, with the exception of global citizenship identification and valuing diversity.

Bivariate correlations

| Normative environment | Global awareness | Global citizenship identification | Intergroup empathy | Valuing diversity | Social justice | Environmental sustainability | Intergroup helping | Responsibility to act | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normative environment | 1 | ||||||||

| Global awareness | .212* | 1 | |||||||

| Global citizenship identification | .499** | .119 | 1 | ||||||

| Intergroup empathy | .236** | .164 | .008 | 1 | |||||

| Valuing diversity | .075 | .208* | -.019 | .023 | 1 | ||||

| Social justice | .226** | .061 | .269** | .077 | .420** | 1 | |||

| Environmental sustainability | .446** | .333** | .284** | .040 | .209* | .255** | 1 | ||

| Intergroup helping | .403** | .348** | .320** | .103 | .271** | .349** | .384** | 1 | |

| Responsibility to act | .315** | .286** | .123 | .250** | .136 | .304** | .230** | .304** | 1 |

**p<0.01, *p<0.05

Structural equation modelling was carried out using Stata to examine the predicted model’s fit. The relationship between antecedents (normative environment and global awareness) and outcomes (prosocial values) was mediated by identification with global citizenship. The disturbance terms of the prosocial variables were allowed to covary due to their related nature. A range of fit and comparison-based indices, including chi-square, was used to determine which model provided the best fit for these data (Bentler, 1990; Steiger, 1990; Browne and Cudeck, 1993; Brown, 2006). The fit indices include root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (S-RMR), coefficient of determination (CD), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI). Hu and Bentler (1999) suggest various cut-offs for these fit indices. To minimize Type I and Type II errors, one should use a combination with S-RMR or the RMSEA. In general, good models should have an S-RMR <0.08 or the RMSEA <0.06 with the fit index values > 0.9.

Information regarding RMSEA, S-RMR, CD, TLI and CFI on these models and the correlations of the individual measures is given in Table 2, showing that the model adequately fits the data.

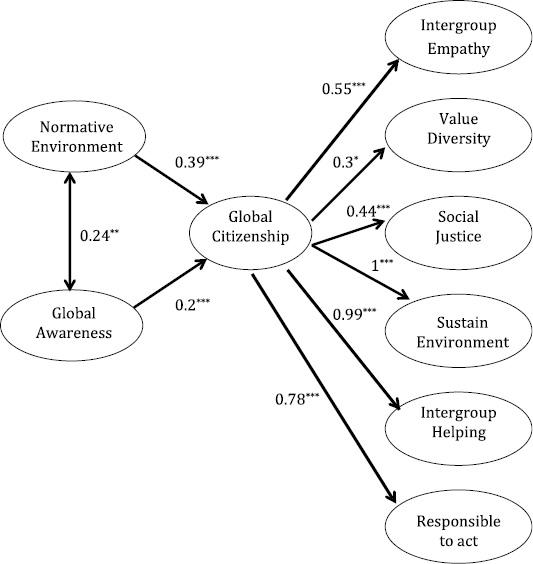

Items all loaded well on each of the factors, including normative environment (.82, .82), global awareness (.51 to .73), global citizen identification (.79, .79), intergroup empathy (.85, .74), valuing diversity (.84, .84), social justice (.81, .81), environmental sustainability (.77, .77), intergroup helping (.83, .83) and responsibility to act (.77, .77). The structural equation model in Figure 1 shows that normative environment and global awareness are positively correlated (r=0.24, p<0.01). Normative environment (β=0.39, p<0.001, CI=0.28 to 0.50) and global awareness (β=0.20, p<0.001, CI=0.10 to 0.28) predicted global citizenship identification. Global citizenship identification predicts intergroup empathy (β=0.55, p<0.001, CI=0.19 to 0.89), valuing diversity (β=.30, p=0.08, CI=-0.04 to 0.64), social justice (β=0.44, p<0.01, CI=0.11 to 0.76), environmental sustainability (β=1.0, p<0.001 CI=0.98 to 1.15), intergroup helping (β=0.99, p<<0.001, CI=0.69 to 1.29) and responsibility to act (β=0.78, p<0.001, CI=0.45 to 1.10).

Model of global citizenshipStandardized betas, *p<0.1, **p<0.05, ***p<0.001

Source: BFI (2015: 7)

In conclusion, it can be said that the research here broadly replicates research previously performed with Reysen and Katzarska-Miller’s (2013) model of global citizenship. There is no doubt that normative environment and global awareness predicted global citizenship identification, which then predicted the prosocial values (for example, intergroup empathy, valuing diversity, social justice, environmental sustainability, intergroup helping and responsibility to act). This suggests, as hypothesized, that the statements on the global citizenship questionnaire are, in fact, pertinent questions to ask regarding global citizenship. However, as the model is only adequate, with just S-RMR and CFI fit indices indicating a good fit, these results could suggest that other factors are involved in what characterizes a person’s perception of global citizenship.

Discussion

A moderate fit was found in the structural equation modelling of the results of the global citizenship survey, showing that the model of global citizenship designed by Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) is an adequate model (S-RMR<0.08 and CFI>0.9) in a variety of circumstances, as agreed by Lee et al. (2017) in their research. This would suggest that global citizenship is not an abstract concept, which Davies (2006) suggested, as this research has shown that it can be measured to some extent in a Ghanaian context.

This research has shown that normative environment was significantly correlated (p<0.01) with all other aspects of the model, apart from valuing diversity. This could suggest that in Ghanaian schools the idea of valuing diverse cultures is not a concept these children have thought about in any detail or come across in their curriculum. This is supported by the semi-structured interviews, where the children reported that they had only thought about getting to know people and cultures from the perspective of their own travel opportunities and not with regard to visitors to Ghana. This result is also supported in the structural equation modelling with a standardized beta value of 0.3 (p<0.1) which implies only 9 per cent of the variance in the factor valuing diversity is explained by the global citizenship latent factor. This is in sharp contrast to other factors such as sustainable environment (100 per cent explained), intergroup helping (98 per cent explained) and responsibility to act (61 per cent explained) where global citizenship is clearly playing a major role. In line with previous research (Reysen and Katzarska-Miller, 2013; Lee et al., 2017), normative environment was the most significantly correlated area of global citizenship within this model, showing that family, friends and those close to a participant have a large impact on their affinity with the concept of global citizenship. This would suggest, given the high level of self-identification as global citizens, that the family and friends of participants have a like-minded approach to the concept, although they most likely will not have heard of the term ‘global citizenship’, given that it is not explicitly taught in the Ghanaian school curriculum.

The study is limited, however, by its small size in comparison to previous research. Even though the age of participants provides an appropriately different context to previous research, it could still be a limitation as younger participants are often more likely to feel an attachment to the world and therefore identify as global citizens (Norris, 2000). Surveying school-age children, as opposed to adults or those already enrolled in university, has widened the context of research that uses this global citizenship model. Caution should be exercised in generalizing results, as this project is the reflection of a small group of children in only three schools in one country. Nevertheless, it adds to previous research by expanding the ages and context of participants and their views on global citizenship, as well as using qualitative data to further interrogate agreement with global citizenship statements than some earlier studies have done.

The research conjectures that the moderate fit of the model may suggest that there are other elements that could contribute to global citizenship and the traits that are present in a global citizen. This research did not address some elements of global citizenship that have been discussed in the literature, but the children discussed these during the interviews. Teamwork, collaboration, interconnectedness and the ability to resolve challenges are seen as important to global citizenship and therefore may be an aspect that could be added in order to make this model a more significant fit (Scott, 2015; UNESCO, 2015, 2019b). The discussion with the children revealed that they were passionate about intergroup helping and how collaboration could help to solve Ghana’s economic and social problems. In addition to this, an understanding of democracy, political systems and their implications were not included in the questionnaire and these could also form elements of future research into global citizenship (Price, 2003; DfE, 2014). Other possible aspects that could add insight to the model used here are criticality, enquiry and reflection in GCE and global citizenship (Price, 2003; Andreotti, 2006; Oxfam, 2015b). The children did not realize that Africa Climate Week was taking place very close to their schools and wondered why they had not been offered the opportunity through GCE to take part in what they all agreed was an important event. Furthermore, two final aspects that could add further to the exploration of this topic is peace and conflict, and pupils’ understanding of how societies work peacefully together. These are all significant aspects of global citizenship and the SDGs, therefore it can be conjectured that further exploration of the views and understanding of students of these areas may further develop the global citizenship model (DfE, 2014; Oxfam, 2015a, 2015b; United Nations, 2015a).

Ghanaian children living in informal settlements overwhelmingly self-identified as global citizens and showed high levels of agreement with each of the statements regarding the outcome and antecedents of global citizenship, even though there appears to be little or no formal GCE in the school curricula. Although there is no explicit teaching of global citizenship topics in the current Ghanaian curriculum, it seems that children do have an understanding of and an affinity with the concept of global citizenship presented here. This would imply that global citizenship is not a form of elitism, as Shultz (2018) has suggested, and offers a possible counter-argument to Torres (2017: 103) ‘trampling our global commons’, given that children who are from very low socio-economic backgrounds and lack explicit knowledge of the topic have nevertheless identified with the concept.