Introduction

This article offers a novel foray into international mindedness (IM) by examining it through a posthuman theoretical lens. International mindedness, as concept and practice, is central to the International Baccalaureate (IB), an educational organization with programmes of study taught in both international and national schools around the world. The IB is underpinned by the aim of achieving a better and more peaceful world. international mindedness, as developed through IB programmes, is, like global citizenship, one of many contemporary modes of global education (Marshall, 2007), albeit one where the concepts, purposes and associated pedagogies of global education/citizenship are contested (Blackmore, 2016). What prompts our particular inquiry in this article is that, while international mindedness, IB and global education programmes more broadly share common foundations in ethics and ethical practices around tackling injustices to make the world a better place, their current framing is indubitably anthropocentric. This limits their ethical range and scope as well as their potential educational efficacy in promoting the values they espouse. This article contends that a broader ethical, ontological and epistemological frame – that of relational becoming – is needed. Given the increasing scale and accelerating speed of the world’s travails – climate emergency, species extinction, mass migration, geopolitical conflict and widening inequalities – it seems imperative to expand the frame of ethics, responsibility and values beyond the limited parameters produced by human exceptionalism and the cul-de-sac of humanist ethics (Taylor, 2018a).

A post-anthropocentric reconceptualization which recasts international mindedness as a relational educational endeavour is, we argue, better able to attend to nonhuman–human entanglements in which agency is a more distributed affair and has an ethics of response-ability at its heart. The term ‘nonhuman’ is important in emphasizing that the world is more-than-human and that nonhuman–human interconnections constitute the world as an assemblage of all living and nonliving matter. Bringing international mindedness into contact with posthuman theory through the Deleuzian-inspired concept of relational becoming provides a powerful analytical frame for reconsidering who matters and what counts in education in a more-than-human world (Deleuze, 1995). This reconceptualization involves rethinking the mind and body dualism, nonhuman–human relations, individual agency, ethics as response-ability and historical legacies of entangled mattering. To illuminate each element of this rethinking, we discuss five ‘material moments’ (Taylor, 2018b) which put posthuman theory to work via empirical pedagogic instances. These instances lead into a broader discussion of the entanglements and contestations around nation-states, globalism, colonial inheritances, elite education and inequalities that continue to inform both international mindedness and the IB more broadly.

The next section introduces international mindedness and its (anthropocentrically framed) educational social justice mission in the context of the IB and global education/citizenship. The following section explores posthumanism and outlines why ‘posthumanizing’ international mindedness is a timely, necessary and promising endeavour. Next, we outline the use, purpose and value of a methodological focus on material moments, deriving from observations at an IB world school in Indonesia. We touch on our entanglement, as white, middle-class academics from the minority world, within the colonialist structures we critique. Following this, the five propositions are outlined, each of which articulates and illustrates one of the five ‘rethinkings’ that underpin our posthuman reconceptualization of international mindedness. The conclusion reaffirms the central argument that the aim of international mindedness – to contribute to a more peaceful and better world – is better framed not within individualistic humanist ethics but as a more inclusive and ethically affirmative mode of relational becoming within nonhuman–human ecologies and educational entanglements. We end by highlighting the difficult conversations that have to begin (and then continue) in order to reshape international mindedness as a mode of relational becoming that is oriented to the pursuit of global social and environmental justice.

The International Baccalaureate, international mindedness and global citizenship education: A contested terrain

Globally there are 5,175 International Baccalaureate world schools in 157 countries, with over a million students aged 3–19. This represents an almost 40 per cent growth in programme uptake between 2012 and 2017 (IBO, n.d.a). The IB comprises the Primary Years, Middle Years, Diploma and Career-related suite of four programmes, which together constitute a ‘continuum of international education’ (IBO, 2014). While the IB is usually regarded as an elite qualification conferring positional advantage and shaping students as future leaders, recent moves to utilize IB programmes to improve state education are evident in Ecuador, Japan, Australia and the United States. In Ecuador, for example, 270 IB world schools offer the Diploma Programme, which, Barnett (2013: 46, 29) suggests, has had ‘a profound impact on state education in Ecuador’ helping to promote ‘a global vision’.

International mindedness underpins an IB education and is described as the development of people who ‘recognizing their common humanity and shared guardianship of the planet, help to create a better and more peaceful world’ (IBO, 2013: n.p.). The international mindedness focus on global values and orientations renders the IB schools and their programmes unique (Drake, 2004). Hill (2012: 245) traces the development of the concept of international mindedness, from an initial focus on:

Students moving to … different countries ... in the mid 20th century … to concepts of intercultural understanding, language learning and human rights, and in the late 20th century and 21st century to … sustainable development, awareness of global issues, and international cooperation.

Contemporary conceptualizations of international mindedness distinguish three interrelated ‘pillars’ – intercultural understanding, global engagement and multilingualism (Singh and Qi, 2013) – which extend beyond academic achievement and engender ‘a commitment to help all members of the school community learn to respect themselves, others and the world around them’ (IBO, n.d.b).

These aims resonate with the posthuman conceptualization of relational becoming which we are developing here. They are also broadly consonant with the aims of global education, an umbrella term (Marshall, 2007) within which a number of ‘adjectival educations’ such as international mindedness, global citizenship education, global learning, development education and peace education are positioned. Like international mindedness, these educations foreground the role played by teaching and learning in tackling global injustices (Blackmore, 2016; Bourn, 2015, 2016), although their emphases differ. Global citizenship education places greater emphasis on action whereas international mindedness privileges a state of mind, potentially leading to action for world peace. Likewise, many analyses of global education (including international mindedness) continue to presume that nations are bounded entities that interact with each other, while recognizing that nations have co-emerged through colonial processes of violence and appropriation. Our posthuman framing rejects the artificial bounds of the nation-state and sees ‘international’ as an unhelpful description of the complex interweaving of human and nonhuman elements and ecologies.

Conceptualizations of international mindedness have expanded recently, in particular in the IB’s acknowledgement of its ‘Western humanist tradition’ (IBO, 2008: 2) and the need to rebalance Western minority and majority world perspectives. Unfortunately, efforts which place sustainable development at the heart of international mindedness are still too often oriented to securing benefits for affluent humans in the minority world, as Smith (2019) and others recognize, and continue to be motivated by anthropocentric considerations around securing ‘the future of the human race’ (Hill, 2007: 246). Some efforts have been made to reframe global education beyond the human. For example, Selby (1999: 127) suggests that ‘biocentric expressions’ in which ‘the human project is decentered … [and] where the well-being of the entire earth community is the primary project’ is required, and Misiaszek’s (2015: 280–1) ‘ecopedagogy’ promotes ‘transformative action by … unveil[ing] oppressive global citizenship models that help to sustain social inequalities caused by environmental ill actions’. These reformulations are welcome and consonant with our contention that the significance of nonhuman life needs to be rendered visible. However, we wish to go further – by placing nonhuman and material agency at the heart of our reorientation of international mindedness. Only such a thoroughgoing shift will enable us to begin to address the importance of the nonhuman and the increasingly fragile nonhuman–human ecologies on our planet.

Recasting international mindedness as relational becoming therefore speaks to the need articulated by Singh and Qi (2013: 2) ‘to conceptualise an approach to international mindedness that is appropriate for the 21st century’. That international mindedness is an ambiguous and capacious concept is potentially advantageous in this respect – as is the fact that IB programmes are diverse and responsive to local understandings, and take into account geographical, political, religious, social and cultural factors in the education of students with disparate experiences and needs across the world (Barratt Hacking et al., 2017). In the next section, we outline what posthuman theory offers for reconceptualizing international mindedness and explain the concept of relational becoming.

What does posthuman theory offer for rethinking international mindedness?

For Braidotti (2019: 1), posthumanism is ‘both a historical marker of our condition and a theoretical figuration’, which, she asserts, has introduced a ‘qualitative shift in our thinking about what exactly is the basic unit of common reference for our species, our polity and our relationship to the other inhabitants of this planet’ (Braidotti, 2013: 2). We share Braidotti’s view that posthumanism offers a creative and critical means to decentre anthropocentricism and its damaging effects on our lives, institutions and the planet, and to replace this with more relational, ethical, political, and ecological modes of understanding and action which attend to the lived materialities of nonhuman–human entanglements (Taylor, 2016). This posthuman orientation – which is theoretically and empirically heterogeneous and capacious – arises from a set of converging critiques of: (a) Western Enlightenment thinking which positions the humanist ideal of ‘Man’ as the universal measure of all things; (b) species hierarchization instituted by Western humanist ‘Man’ in order to obtain dominion over, and use of, other nonhuman beings, and which has led to species extinction on an unprecedented scale as well as the global depredation of the natural environment; (c) colonialism as a global political-economic-racist strategy to enable white, Western, minority world ‘Man’ to control other ‘inferior’ humans – practices which continue to be sustained through global, neocolonial practices; (d) the many binaries, divisions, hierarchies and distinctions that flow from these practices of ‘othering’, such as man/woman, adult/child, theory/practice, body/mind, self/other, reason/emotion, human/nature; (e) the precedence of hyper-capitalist, neoliberal, extractive economic imperatives which reduce all of life to what can be bought and sold; and (f) modes of techno-necro-politics oriented, on the one side, to global armed warfare ‘at a distance’ and, on the other, to the mass surveillance and intimate control of populations and their politics (see Braidotti, 2013, 2019; Taylor, 2016, 2019).

Posthumanism is a capacious label that includes many varieties (Taylor, 2016). It is important to note that the posthumanism we are working within is not a posthumanism which erases the human or which sees the human as perfectible by scientific or technological intervention, as some modes of transhumanism do. Rather, it is a posthumanism which decentres the human thereby to consider the human in relation. This posthumanism sees humans as embedded and enmeshed, not as a separate category from ‘everything else’ (Taylor, 2016: 8); it is an ethico-political orientation requiring us to live in the knowledge that ‘the Earth we inhabit is not an optional element’ (Braidotti, 2020: 27). The posthumanism we activate is not abstract but practical, firmly grounded in the present actualities of the material-discursive relations that emerge and are constitutive of the educational practices that unfold and matter to those involved. The critique of ‘human’ as privileged category underpins our reconceptualization of international mindedness as posthuman relational becoming. Inspired by Deleuze and Guattari’s (1987) philosophical notion of becoming as an immanent unfolding of the ‘self’, of change as ongoing flux and dynamic flow, as a continual process that comes about through the ongoing work of differentiation. Relational becoming is grounded in this notion of change as immanent and emergent. Importantly, it moves beyond notions of individualized, bodied humans to apprehend the ways in which ‘I’ only emerges within nonhuman–human assemblages of intensities, forces, affects, desires, instants and materialities. Relational becoming, then, refers to an open process of relational experimentation ‘on ourselves [involving] all the combinations which inhabit us’ (Deleuze, 1995: 44) – education, nation, nature, environment, world, cosmos – and in which we are enmeshed. As an educational praxis, relational becoming offers pedagogic opportunities to ‘bring into being that which does not yet exist’ (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994: 174) and proffers a mode of coexistence oriented to a more ‘sustainable present and a [more] affirmative and hopeful future’ (Braidotti, 2019: 3). Given that international mindedness is ‘a process rather than a product; a journey rather than an arrival … constructed and social’ (Barratt Hacking et al., 2018: 14), then relational becoming seems particularly apt as a means of reconceptualizing international mindedness.

Posthuman theory is increasingly used within educational research, including in childhood studies and early years education (Somerville and Williams, 2015) and higher education pedagogies (Taylor, 2019). Posthumanist approaches have been instrumental in reorienting educational research away from ‘seeing, observing, and knowing from afar’ to focusing on ‘entanglements and relationalities … [and] on making and marking differences from within as part of an entangled state’ (Ivinson and Renold, 2016: 171). Snaza et al. (2014: 40) suggest that posthumanism offers opportunities to ‘transform educational thought, practice, and research’. Our article aligns with these recent endeavours and uses posthumanism as a conceptual tool to help us rethink the possibilities for recasting international mindedness as relational becoming in a post-anthropocentric world.

Methodology

The analysis deploys a methodology of ‘material moments’ (Taylor, 2018b) as an innovative approach to focusing on the material-discursive import of often micro, fleeting and happenstance events, practices and occurrences that are affectively charged and possess felt significance (often beyond the register of the verbal) for those involved. This approach aims to locate ‘instances, occurrences and interactions which inhere in, and are enacted through, the materiality of bodily relations; they are moments which are materially dense and specific … time-bound and spatially-located’ (Taylor 2018b: 157). Material moments, in their focus on nonhuman–human materialities, move beyond the anthropocentric gaze, even though data are derived from the human researcher’s inquiry (diary, photographs and social media posts). The material moments are considered as ‘data hotspots’ in MacLure’s (2010) helpful formulation. They were moments which ‘glowed and glimmered’, instances which ‘jumped out’, ‘grabbed attention’ and sparked pivotal memories and connections. A methodology of material moments offers an appropriate approach for tuning into the location’s specificity and the school’s diversity, which Dvir et al. (2018) consider so important when researching global educational contexts. They are also apt for our stance as white, privileged academics with a desire to refuse generalizations while accepting our entangled accountability within the shifting neo/colonialist machines of global teaching and research.

The data were generated during a four-day visit to a fee-paying English-medium IB world school for 3–18-year-olds in Indonesia, a diverse Islamic nation with over 300 ethnic groups. The visit was undertaken as part of a study of international mindedness thinking and practice in nine IB world schools (both state and private) nominated for their promising international mindedness work (Barratt Hacking et al., 2017, 2018). The research obtained ethical approval from the IB, from the University of Bath and from the school. Pseudonyms have been used to protect anonymity. The data in this article draws on Author 1’s personal record of this visit rather than on data collected for the wider study.

The school has European roots (for anonymity the specific European country is not revealed). With the support of businesses and their country’s embassy, it was established in the 1970s by a group of European parents, who, located in Indonesia, wanted a European education for their children. It was approved as an IB world school in the 1990s and now caters for a diverse student body. At the time of the visit 43 per cent of 16–19-year-old students were Indonesian, with a further 25 nationalities represented. While a majority of the teaching staff and leaders are European, the non-teaching staff are largely local, a pattern which is typical of international schools (Tarry, 2011). The school’s European-Indonesian history and contemporary formation is indicative of the troubled entanglements that characterize colonizer–colonized education arrangements. This is exacerbated both by the school’s adherence to European values within an Islamic nation and by privilege in a context of local poverty (Moraes, 1998). Tensions are evident between the IB ‘elite’ mission – to educate world leaders towards a better world – and the desire for a more democratic education. Nevertheless, the school’s promising international mindedness practice offered scope to explore relational becoming within the local–global assemblage and for attending to questions of response-ability and colonial entanglements.

We now turn to our five propositions, outlining and then discussing each in relation to one of five ‘material moments’. While each material moment is located within the dense and specific particularities of the school, we hope that their educative value resonates for international mindedness, the IB and global education more broadly.

Putting posthumanist theory to work to reconceptualize international mindedness

Beyond mind and body binaries: Building a motorbike

Proposition 1: Nonhuman–human relational becoming is a holistic approach of becoming, doing and experiencing which foregrounds bodily experience and body and mind connectedness.

Box 1: Author 1’s diary extract, day 3

The students (year 12 Diploma Programme students, aged 16–17 years) told me about an activity in their CAS (Creativity Activity Service) programme in which a 17-year-old boy from the kampung, Rendy, had worked with a group of them to take a motorbike apart and rebuild it over a period of weeks. They said Rendy had never been to school but had taught himself motorbike maintenance from working on scrap motorbikes. Students recalled how, once they had taken the motorbike apart, they were surrounded by cardboard boxes of 100s of pieces: intricate metal, plastic and rubber parts covered in black grease (them and the parts) with the larger parts now cleaned up and shiny. They were in awe of Rendy’s ability to work with this chaos of parts as they themselves came to enjoy working with the intricate pieces and seeing the parts cleaned, rearranged and transformed into a working whole. They described how building this motorbike was a significant IM [international mindedness] experience. One boy said it wasn’t just building a motorbike – it was building a bond with Rendy, and a glimpse into his life. They seemed both stimulated by it and emotionally moved by it. Later some teachers talked about the motorbike build as well. One teacher told me he thought this experience, and other experience of working with community, was transforming the students.

At the curriculum level, building a motorbike is associated with international mindedness. It is clear from this extract that the experience is not about mindedness alone but is a sensory activity-experience that involved mind and body, movement and practice, thinking and doing: the students worked with the material parts of a motorbike, with each other and with Rendy. Students’ experiences enmesh mind, body and senses. The materialities entailed in building a motorbike are the very same materialities that enable the students to build an emotional bond with each other and with Rendy, the boy from a nearby kampung (an Indonesian term, originally meaning ‘village’ but now used to describe a poorer neighbourhood within a city) which, although geographically close to the school, is very distant from these students’ lives. This mode of learning included the acquisition of skills, discovering more about Rendy’s life and expertise, and learning about the kampung community, about themselves and each other. As an affectively bodied activity-experience, the shared material realities of motorbike building radically shifted the paternalistic, charitable, service-like models of ‘Western’ education that exacerbate the stereotypical, negative imagery of those ‘in need’. The students’ admiration of Rendy, their openness to following his leadership and teaching, in some way displaced the practices of ‘othering’ that are central to many Western, minority world, colonial educational traditions.

This material moment challenges the use of the term ‘mindedness’ in international mindedness. Posthuman theory rejects binary thinking (body/mind, nature/human, them/us) and the valuing of the mind over the body. Dualism is embedded in Western, Enlightenment, minority world thinking. Descartes proposed that the mind exists without the body, that ‘the mind is privileged over the body, or put differently, contemplative life is superior to active life’ (Murris, 2018: 4). Posthumanist thinking proposes a more relational way of thinking which brings to the fore the entanglement of mind–body–spirit–heart and the intra-active interconnectedness (Barad, 2007) of the material, natural and cultural in each educative instant. This aligns well with Barratt Hacking’s et al. (2017) approach to international mindedness research in schools which developed the model of ‘head, heart and hands’, just as the material moment of building a motorbike combines body and mind, doing and thinking, practical and theoretical, relating and looking-in. We cannot, of course, speak for Rendy. It may be that he experienced a reversal of his position: powerless to powerful, recipient to donor, silenced to spoken, unschooled to expert. What we do know is that this was a significant experience for the students, which prompted them to question the similarities and differences between their own lives and Rendy’s and to recognize the systemic barriers that hold social inequalities in place. As such, this experience was, we suggest, a pedagogic moment of relational becoming, possessing the potential for generating different futures with Rendy and the kampung community surrounding the school. Yes, it is only one material moment – but it holds the promise of a more expansive pedagogy for recasting international mindedness and enabling this IB school to adopt a more ethically relational space with/in its community.

Nonhuman–human assemblages: Barbed wire and dogs

Proposition 2: Nonhuman–human relational being acknowledges the world as an entangled assemblage of mutually dependent relations.

Box 2: Author 1’s diary extract, day 1

We crawl along a highway congested with rush hour traffic: expensive cars, scooters, lorries, vans, carts. People fill the roads. The highway is lined with glittering skyscrapers and tall palm trees. Billboards advertise new housing complexes, college courses and shopping malls. Behind and between there are informal dwellings, derelict spaces and smoking rubbish piles. Clothes hang on washing lines, belongings spill outside: chairs, tables, boxes, clothes, cupboards. A woman is pushing her food cart the wrong way up the busy slip road onto the highway. In the distance – a haze. The driver says the rainforest is burning. The heat, smell and noise are palpable inside the air-conditioned car (see Figure 1).

We arrive: high walls and barbed wire surround the campus. A long black tarmacked drive passes green lawns and trees either side. A line of cars lead up to a barrier … drivers with one or two children in large shiny cars. Two tall security officers in black uniform each holding the leash of a large lean menacing black dog, ears pricked up, alert; they stand at the side of the car still and silent. We are stopped and checked. Through the security barriers the campus opens up: green hedges; tennis courts; adults in white tennis kit coaching small groups of children. Ahead I see architecturally Indonesian modern school buildings, more lawns and gardens.

Walls, barbed wire, dogs, security guards, security barriers, smoke from the forest fires, cars, children, rubbish, insects, heat, smells, lawns, uniforms, birds, trees, boxes and, and, and … all of these nonhuman and human entities exist and intra-act, forging relationships, taking their place in what Barad (2007: 169) calls the ‘specific material configurations, or rather, dynamic reconfigurations of the world’. We have argued that international mindedness privileges anthropocentric understandings. A posthuman understanding – in which international mindedness is reshaped as a more capacious mode of relational becoming – would, instead, attend to the assemblage of nonhuman–human relations which orients learning towards the nonhuman world – as the forest smoke so urgently indicates.

Deleuze and Parnet (2006: 52) define assemblage as: ‘a multiplicity which is made up of many heterogeneous terms and which establishes liaisons, relation between them [whose] only unity is that of a co-functioning: it is a symbiosis, a “sympathy”’. Assemblages are an ‘emergent, temporarily stable yet continually mutating conglomeration of bodies, properties, things, affects and materialities [that] combine together in complex configurations that seem momentarily stable’ (Taylor and Harris-Evans, 2018: 1258). Assemblages work via relations and alliances. They are not background structures, static situations or stable entities – they are active, always emergent and always in flux. They forge relational confederations of bodies, objects, spaces, affects, forces and desires which traverse boundaries as they mesh momentarily. This material moment illuminates a series of boundary-making practices at work in the particularities of this assemblage: an elite school, controlled movement in and out of it, a border between poor and rich, voiceless and powerful, them and us. It tells a local story of the juxtaposition of affluence and poverty – which is, of course, a global story. Author 1’s discomfort is keenly felt during her air-conditioned journey (see Figure 1): she is enmeshed in the boundary-making practices that materialize her as a privileged academic and separate her from the noisy and ‘othered’ outside. The school, we might think from this example, materializes as an elite ‘container’ for privileged bodies: the walls, lawns and tennis courts of this European school in Indonesia continue to materialize power relations inherited from the colonial past in which European teachers educate children of the elite for future leadership beyond its walls.

A posthuman perspective draws attention to these boundaries as anthropocentric constructions. Nonhumans and humans of all kinds move through these walls. Cars, vans, drivers, food, paper, digital networks, people (young and old, Indonesian and other nationalities), parents, teachers, gardeners, cleaners, dogs, plants, trees, birds, smells, the wind, ideas and much more permeate the barbed wire barriers. Nonhuman–human relations of all kinds develop and coexist between the school and the local community, indicating how local–national–global worlds are connected and coalesce. Boundaries and borders are colonizing effects of human dominance. In its current articulation, international mindedness works with a presumption of borders and boundaries. Relational becoming problematizes this. Posthuman assemblages come into being across borders; they take no account of barriers (think of the forest fire and the smoke) but they do bring to attention where, how and why barriers are erected and the exclusionary work they do. Noting this can, we think, lead to powerful material–relational learning and to more ethically engaged action to challenge the damage caused when privileged humans disregard humans and other components in the assemblage of human–nonhuman relations for their own ends.

Distributed agency and cross-species understandings: The indigenous garden

Proposition 3: Nonhuman–human relational becoming presumes that agency operates via distributed ontologies and opens up cross-species understandings.

Box 3: Author 1’s diary extract, day 1

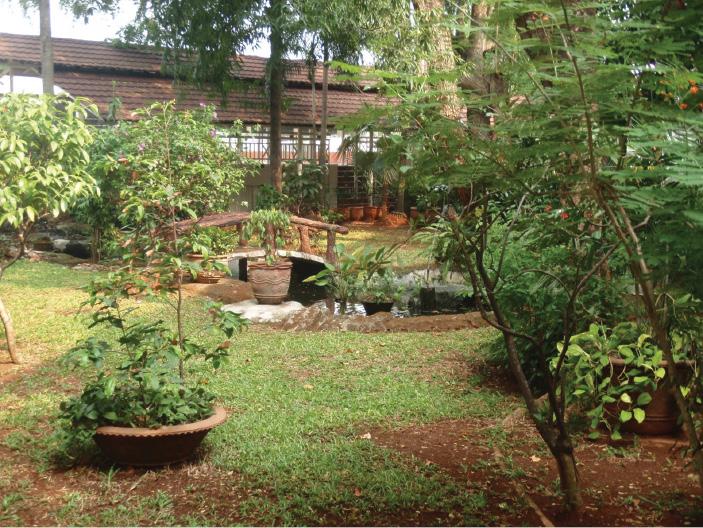

Exploring the school grounds. There was no one around, classes were on. Beautiful – so green, so shaded and still – in the tropical heat – a rainforest garden – an enclave within a depleted local environment. Birds singing, insects humming. The modern school buildings with sloping and overhanging rooves, and outdoor covered spaces: colonial architecture alongside vernacular Rumah Adat styles. The grounds are abundant with trees and indigenous plants, streams and bridges (see Figure 2). There are other cultural features. Stone circles form meeting places. International flags fly from the main building. Student art decorates the garden: hand painted maps on a wall; an Indonesian village model; colourful masks and other artefacts are hanging from the trees (see Figure 3). Signs warn of electric storms, and what to do in the event. A number of gardeners, local staff, are hunched over their work in their green and earth-coloured uniforms, screened from the sun by wide-brimmed hats, working quietly and methodically. A bell went off and suddenly the grounds were full of children moving along the walkways between buildings to their next lesson, then quiet again.

In posthumanist thinking, the agency to act is shared across the socio-material world: humans, nonhumans, plants, objects and things have agentic capacities. Bennett (2010: 32) refutes the idea of human intentionality as the only force able to bring about change and, instead, proposes the idea of distributed agency to represent ‘a swarm of vitalities at play’. Distributed agency acknowledges that nonhuman forces, forms and matter (such as the sun, storms, water, gravity, electromagnetism) act together in distributed agency. Barad (2007: 33) challenges the minority world, humanist view that there are separate individual agencies that precede their interaction and argues for the need to replace this with the notion of ‘intra-action’ which ‘recognizes that distinct agencies do not precede, but rather emerge through, their intra-action’.

This powerful reconceptualization of ontology and agency brings to the fore that, in the garden, the gardener is not the only agency, but that the indigenous plants, the soil, the worms and other creatures, the nutrients and bacteria in the soil, the weather intra-act together as mutually entangled agencies of change. These agencies further intra-act with the art, design, architecture and artefacts produced by students who pass through and make art for the garden. All, through their intra-actions, co-constitute the garden as a living classroom, a vital assemblage of matter, enmeshed in the life of the school and entangled with the wider Indonesian culture, society, habitat and history. More than this, the garden – as an instantiation of indigenous ways of being–doing–thinking – is a living teacher with living pedagogies. Majority world and indigenous worldviews are so often neglected in minority world education (van Oord, 2007) and global education (de Sousa and Andreotti, 2008), and yet indigenous communities, like the Sumatran Orang Rimba (who live in this region), continue to work with nature’s cycles for the mutual benefit of everything by connecting nonhuman, human and spiritual worlds (Elkholy, 2016). The garden’s agency makes it a vibrant and vital place: a habitat for plants; a creative space for art, design and architecture to merge; a home; a place of employment; a place to grow; a precious habitat for nonhuman nature in an urban desert; a place to retreat, rest, think, learn, meet or play; a spiritual place. The indigenous garden, as a hybrid place which both materializes and contests enduring and entangled colonial legacies, is a place of and for the potential emergence of relational becoming. Posthumanism, then, provides international mindedness with the conceptual and practical tools to enable us to ‘rethink and rework what the rising generation of local/global citizens needs to be, to say and to do in the changing local/global order’ (Singh and Qi, 2013: viii). The indigenous garden and its intra-active potential might prompt students to develop a more distributed conception of their agency as global citizens (Häkli, 2017), an agency that brings with it new modes of ethical response-ability as we discuss below.

Ethics and response-ability: Sekolah Aman

Proposition 4: In pursuing a better, more peaceful world, justice and ethics should be expanded to include nonhuman–human response-ability.

Box 4: Author 1’s diary extract, day 2

Sekolah Aman, a school for 25 ‘unschooled’ children, was created by IB Diploma students in partnership with the local community and a business. IB students manage Sekolah Aman. They are responsible for accounts, purchasing food, uniforms and learning resources, arranging transport for the children, fundraising. IB teachers support them by advising on the curriculum and teaching occasional lessons.

We arrived, a mini green oasis. A line of small children greet us Indonesian style, huge smiles on their faces, and dressed in colourful batik shirts. It is an open-air school, set in the grounds of a multinational company which provides sponsorship. Built in steel and bamboo with a thatch roof, classrooms are divided by plants, bamboo and bookshelves (see Figure 4). Vegetation and building intertwine; vines creep up the chalkboard and down the bamboo divides; the external bamboo screens are alive with orchids, creepers and ferns.

The children have spent their previous short lives begging or scavenging on the rubbish tips, toxic from the burning plastic. I met the gardener (see Figure 5), two teachers and a cook/helper, all from the local community; the gardener was also previously scavenging. Every day the school provides a meal of fresh local food, cooked in situ for the children and staff. The teacher is a former pupil of Sekolah Aman. Following a scholarship into secondary education he is now studying accountancy at night school and works here every day.

Indonesia’s economic growth since the 1990s has enabled it to become ‘the largest economy in Southeast Asia’ (World Bank, n.d.). Nonetheless, 25.9 million out of a population of 264 million still live below the poverty line and one in three children under the age of five is malnourished and living in a polluted environment (World Bank, n.d.). This material moment highlights the IB school as an entangled agency within unjust global capitalist relations in which extractive wealth for some produces impoverishment for others.

In such a context, what can an ethics of response-ability do? Dobson (2005) argues that justice is more appropriate than obligation or charity as a driver for change as it suggests a potential for rebalancing relations. One teacher commented that, through their work with the school, the IB students are developing an orientation towards justice for local children (and adults). The micro-level of food provision matters in that it can offset the worst effects of extreme poverty. Students are not merely exercising responsibility — care for the other — but enacting response-ability – the ability to respond in ongoing and appropriate ways to injustice (Barad, 2007; Haraway, 2008). Response-ability is about relational ethics, about being affected concomitantly and responsibility with not for. Response-ability is not a human individual responsibility; it includes all manner of response by all matter. At Sekolah Aman the community works together to respond to injustice; its former students and local people play key roles (for example, teacher, cook, gardener) in reciprocity. The IB students work collaboratively to support access to healthier food, fresh air, green space, healthcare, clothes (batik uniforms), safe transport and education. Nonhumans – such as indigenous vines, creepers and flowers and other wildlife – also participate by creating a space for spiritual nourishment, as capitalist environmental depredation has resulted in the absence of indigenous plant life in the kampung. Haraway (2016) says that such efforts of ‘making kin’ across nonhuman–human assemblages require us to ‘stay with the trouble’ on what is an increasingly damaged planet. The Sekolah Aman school offers hope for supporting indigenous ecologies. The students are able to use the resources of their privileged education to push back a little against social inequalities that surround them and their school (Moraes, 1998). While these efforts are modest, they are not insignificant in pointing towards how relational becoming might expand international mindedness to include more responsive and response-able pedagogies oriented to social justice practices.

Entangled de-colonial histories, memories and modes of memorializing – poppies and the remembrance wall

Proposition 5: Relational becoming attends to entangled histories, nonhuman–human connectivity and responsiveness across past, present and future.

Box 5: Author 1’s diary extract, day 1

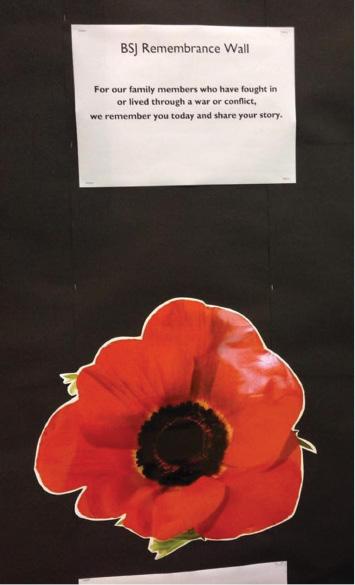

Poppies on display in the school entrance hall (the text reads: ‘For our family members who have fought in or lived through a war or conflict, we remember you today and share your story’) (Source: Elisabeth Barratt Hacking, 2015)

Today a group of students took me on a tour of the school. As we approached one of the entrance halls[,] huge boards of students’ work and red poppies were on display (see Figure 6). It seemed incongruous to see poppies and student memories of WW1 so far from Europe, and the poppy fields of Northern France in a school in Indonesia with so many local students. The students explained that they had collected war memories from their older family members and friends then presented written memories and photographs alongside images of poppies, the symbol of WW1. It was moving to see memories of friends, families and nations who were once former enemies displayed side by side. I realised that Remembrance Sunday was approaching.

The red poppy (scarlet corn poppy, popaver rhoeas) flowered on the barren soil of Flanders Fields following the First World War battles in northern France. In Europe the poppy possesses ‘many meanings and stories’ and has come to symbolize bloodshed and loss, regrowth and peace, sacrifice and nationalism (Murakami, 2017: 4). In an Indonesian setting, this particular poppy species might seem incongruous. Indeed, Author 1’s initial discomfort is evident: she sees the poppy through the lens of her own European heritage, having been unaware of Indonesia’s role in the Second World War and that the use of the poppy to remember fallen soldiers is so widespread. However, both the Indonesian students and those of other nationalities also have deep affiliations with the poppy as matter and symbol, which both troubles and disperses its European affiliations.

Posthuman theory, with its focus on the agency of vibrant matter, urges us to consider the political–cultural work done by such imaginaries as the poppy. The poppy as a natural–cultural object resonates across nonhuman–human boundaries, potently bringing to the fore in the present the past entanglement of history, nation and identity. For Barad (2014: 276), ‘entanglements are not unities. They do not erase differences’; rather, the poppy is doing the work of ‘cutting together-apart’. That is, the poppy as material agency is memorializing Indonesia’s past as a colony of Portugal, Britain, France and The Netherlands, bringing to bear the colonial legacy of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) with its experience of conscription, food shortages and social unrest in the First World War and the later Japanese invasion in the Second. As evocative object (Turkle, 2007), the poppy is enfolded with students’ familial and nonhuman histories and memories: their families’ origins from around the world, soldiers, allies, enemies, weapons, horses, trenches, propaganda, fields, protests, descendants, nations and more – and then more. The poppy becomes a material memory of nonhuman–human destruction and suffering diffused across generations and places, and a troubling point of connection among these.

Barad (2014: 176) urges us to attend to each ‘bit of matter’ within its web because only then can we apprehend ‘its unique material historialities and how they come to matter’. The First World War was nearly a century before the students were born, yet the poppy has the potential to move them through a ‘spacetimemattering’ (Barad, 2007: 383) towards collective recognition of intergenerational memories of wars and their injustices. The poppy helps students to ‘carry the agents, objects and circumstances of remembering along’ (Pentzold, 2016: 1). The remembrance wall offers a suggestively potent form of international mindedness practice recast as relational becoming. This unsettles Eurocentric perspectives on war in school education by connecting plural perspectives, diverse places and nonhuman and human agents relationally through time. In this way, then, the remembrance wall materializes a local micro-political practice that may well contest colonial legacies in education. If so, it indicates how objects, as nonhuman agencies, might take their place within pedagogic endeavours that promote relational becomings oriented to ‘doing’ decolonization.

This more capacious take on how objects come to matter differently is, we think, part of the promise of posthumanism for recasting international mindedness.

Conclusion

This article offers a reconceptualization of international mindedness, suggesting the need to replace it with the concept and practice of relational becoming to help us take better account of relations across the nonhuman–human world. The novel posthuman framework we offer challenges existing anthropocentric understandings of ontology, epistemology, methodology and ethics which are currently embedded within international mindedness and the IB more broadly. This theoretical framework has been developed via five propositions and put to work through five material moments which offer empirical instantiations of how the theory enables us to think and act differently in pursuit of a more peaceful and just world. The material moments are micro-instances of school life and pedagogic practices that often go unnoticed, but which reveal our intimate connections with the more-than-human world. The article indicates that this novel approach has potential for international mindedness, the IB and global education more broadly by enabling a shift from anthropocentric to ethical-relational ways of being that work towards nonhuman and human justice.

Relational becoming reconceptualizes international mindedness in a more capacious, nonhuman–human frame. It recognizes the value of relational learning in widening our human capacities to confront past injustices, attend to the unfolding of the world in the present moment and to reach forward to becoming more ethical-relational and response-able in our actions and practices. It shifts the attention of international mindedness from national boundaries–international thinking to relational spaces (past-present-future), and from human exceptionalism to nonhuman–human assemblages. Relational becoming contests the binaries which humanist, Western education has installed and secured for so long and, thereby, offers a more holistic approach that integrates mind, body, heart and spirit. In this, it prompts learning that is collective and connected so that, through interspecies modes of ‘making kin’ (Haraway, 2016), we might persevere with the trouble of trying to make a better, more peaceful world – for all worldly inhabitants, not humans alone. This is not easy. Entangled as both authors are in Eurocentric educational and research practices, we are ourselves attempting to become less deadly, less racist, more response-able. We began writing this article a little while before the Australian bushfires and subsequent floods killed or displaced 3 billion animals (Readfearn and Morton, 2020). We did the revisions and resubmitted it in August 2020 as lockdown eased and the UK emerged from the first Covid-19 wave with almost 36,000 deaths locally and 662,000 globally – totals which hide the racial and socio-economic inequalities in the distribution of vulnerability and mortality. These crises are intimately linked to our anthropocentric hubris. Perhaps we are now at a turning point when our shared posthuman condition has to be reckoned with (Braidotti, 2013). We sorely need an education that enables children, young people and adults to think and act differently for global social and environmental justice.